Exhaustion, pride and camaraderie: one London hospital trust’s experience of the pandemic

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Segun Olusanya, an intensive care doctor at London’s University College Hospital, heard of a new and highly transmissible variant of Covid-19 in November, he felt the worst kind of déjà vu.

After more than 18 months battling the pandemic, and seeing both fellow clinicians and patients die, he had to ask himself whether he could withstand yet another wave. “Each wave leaves a scar . . . so my big worry with Omicron is, will this be the scar that makes me stop?”, he reflected.

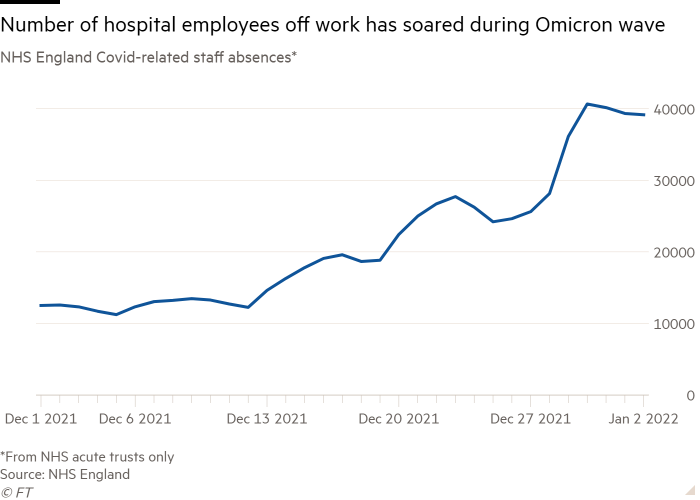

While London is no longer the national centre of the Omicron surge, with numbers now rising in the north of England, staff in the capital continue to work flat out, in part due to very high absence levels among colleagues sick or self-isolating from the disease.

Conversations with an array of frontline staff at UCLH, one of the capital’s biggest hospital trusts, revealed a group buoyed by camaraderie and institutional pride but permanently altered by distressing experiences. They spoke of personal relationships frayed by the intense professional demands of the pandemic, and of exhaustion and burnout after being pushed to the limit and beyond.

The strains have been exacerbated by staff shortages. The number of staff voluntarily quitting the UK’s publicly funded NHS rose more than 40 per cent in the quarter ending in September, compared with the previous three months, according to official data — an exodus that an understaffed service can ill-afford.

Amid a jumble of impressions from the height of the outbreak, Olusanya recalled “the heat and the stickiness . . . when I remember things I remember them through this very hazy blur of visors”. He added: “You’re trying to do a job that certainly I’ve been trained to do for a very, very long time, but you’re trying to do it while wearing a spacesuit and barely hearing people, with 10 times the [usual] number of patients and trying to deliver the same degree of care.”

At UCLH, as across the country, Omicron has not filled intensive care beds like previous strains. Yet the cumulative impact has been immense for staff who have been fighting on the Covid frontline for so long.

“People are burning out . . . We all come here to care for our patients but I feel like people are getting to that point where they’re just saying ‘Oh God I can’t bear to think of having to do it all over again’,” said Louisa Weighill, a critical care physiotherapist.

Olusanya said he loved his job and cared deeply about his patients “but no one should be forced to do something that they love at the cost of themselves”.

Yet there have been positives: new, more collaborative ways of working have emerged, along with a culture in which staff feel freer to acknowledge that they are struggling with mental health problems and to secure the support they need.

Sarah Burton, the trust’s lead cancer nurse, said: “We’ve got much better at checking in with people and noticing if people seem a bit quiet, or mentioned they haven’t been sleeping well, and we tend to pick up on that much more and look after each other.”

The esprit de corps that has helped them get through the emergency can be a double-edged sword, however. Anna Batho, a psychologist who works with both staff and patients in the intensive care department, highlights an ingrained NHS culture of putting collective, ahead of individual, need. When colleagues seek her help “every single time I say ‘have you thought about taking some time off because you’re telling me that you’re struggling’. And they’ve said ‘but what would my team do?’”

All those interviewed felt changed by the experience of the past 22 months. Elaine Atkins, a radiographer now working as a “vascular access specialist”, said she has become far more anxious and so concerned about keeping safe that she has seen friends just three times since the pandemic began. Instead, she returns after each shift to her home round the corner from the hospital, always alert for a summons to return.

She emphasises that she enjoys her role. “I am lucky in the fact that I can come to work and interact with people. But I am also exhausted,” she said.

Batho has found that relationships have had to be renegotiated due to the pressure of the pandemic. “I had friendships or relationships that stopped because they didn’t want contact with me because of where I worked,” she said, adding that “even now, with Omicron I’ve had people cancel social arrangements because they think I am high risk”.

Olusanya, who has combined his work in intensive care with preparing for exams to secure a promotion, describes himself as “pretty broken, pretty exhausted. Basically I’m having to relearn how to live a normal life.”

Memories of those who have been lost are rarely far from the minds of UCLH staff. Among Burton’s most poignant moments during the pandemic was receiving her first dose of Covid vaccine. Relief that she and her family were protected was mingled with guilt “that I’d made it to that point when so many other people hadn’t”.

Adding to the emotional strain for staff has been witnessing the number of people whose care has been delayed, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

Olusanya recalled the first patient he saw, at another London hospital, whose condition had deteriorated so far that life-saving surgery was no longer possible. “It’s profoundly morally distressing . . . it was somebody who had had their heart surgery delayed by six months and they couldn’t have it any more because they turned up and they were too sick.”

He said he and his colleagues began to see more and more people “with delayed presentations of heart disease, cancer and it’s such a difficult thing to hold”.

Arup Sen, a stroke consultant, faced similarly wrenching situations, with some patients only seeking help several days after falling ill. “They were missing the time-critical period for treatment, which is usually within the first few hours,” he said. “It is quite difficult as a clinician to deal with that, knowing if they had come in earlier we could have made more of a difference.”

Yet, for all the psychological support on offer to staff, Batho believes it is important not to “pathologise” a natural and human reaction to all they have lived through and seen. “I think ultimately, it’s not so much wellbeing support that we need, it is more people to help, it’s trained doctors, trained nurses, trained therapists,” she said.

Her comments speak to the endemic staff shortages in the health service. The NHS, which last published a detailed workforce plan in 2003, entered the pandemic with about 100,000 vacancies.

Olusanya also emphasises the need to address recruitment and retention. “I’m six months away from being a consultant, and at the moment, basically, if I throw a stone, I’ll get a consultant job because there are vacancies everywhere,” He said, adding that while this may seem positive, “it’s not great for me, because I’m still going to be working in a system without enough people to pick up the slack”.

Flo Panel-Coates, chief nurse, said the trust had worked hard to accommodate staff who sought a break “so that they don’t leave the profession”. However, she also highlighted the number who were redeployed to critical care at the height of the crisis and had elected to remain: a phenomenon she dubbed “post-traumatic growth”.

Even as staff come to terms with what they have endured over the past two years, all are keen to stress the extraordinary rewards of their work.

Batho said: “Our team work was such that more people survived in our intensive care unit than people died, and you’re there witnessing the people coming through and you’re there talking to the families.

“They were the ones showing this resilience and hope . . . So often when I’m talking to [my] family and friends I’ll say ‘you don’t realise how lucky I am to get to see that’.”

Comments