Jewellery by artists from Picasso to Grayson Perry reaches new heights

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Exhausted by the emotional cost of bringing his antiwar masterpiece “Guernica” into existence, a spent Pablo Picasso retreated to the south of France in the blazing hot summer of 1937, joined by friends including photographer Lee Miller, poet Paul Éluard and artist Eileen Agar. As the group frolicked on the beach, Picasso discovered a shard of art nouveau pottery, glanced up to see Nusch Éluard, Paul’s wife, sunning herself and etched her profile on to it. He later strung it on to a necklace as a memento of this moment in the sun, with the inscription “For Nusch, PP” on the reverse.

Far from being an inspired one-off, this was one of many pieces of jewellery Picasso made during his lifetime, which are now — along with wearable works by many other artists — commanding high prices from serious art collectors.

“Artists’ jewellery has been overlooked for so long, but this niche has become fashionable of late,” says Didier Haspeslagh, who runs Didier Ltd in London with his wife, Martine. The duo will present more than 200 pieces, which include the necklace Picasso made for Éluard, at Masterpiece London (June 30-July 6).

London gallerist Elisabetta Cipriani, who deals in jewels by more than 30 artists, says the market has transformed over the past decade. When she opened in 2009, she received one inquiry for this type of jewellery every two months. Now, she gets five a month, plus unsolicited knocks on the door of her by-appointment gallery.

As for why so many jewellers have embraced jewellery as a medium, their motivations vary. Giacometti turned his maquettes into necklaces to pay the rent at the beginning of his career. Sophia Vari made miniature versions of her sculptures in plasticine to pass the time on distant flights. Braque discovered jewellery at the end of his life, when illness left him bedbound but no less desirous of creative expression.

Among the most sought-after artists’ jewels are those by Picasso, Man Ray, Dalí and, in particular, the sculptors Alexander Calder and Claude Lalanne, prices for which have surged in the past decade. In 2013, a sculptural shoulder-to-navel silver necklace by Calder sold at Sotheby’s for $2mn. A more wearable gilt Dahlia necklace by Lalanne smashed an upper estimate of $6,000 by almost 20 times to reach $113,000 at Christie’s in March.

“When we were starting out 30 years ago, we could buy Picasso and Dalí jewellery for just a few pounds or [the] scrap [price],” says Haspeslagh. Now, however, there is a greater appreciation that these jewels are not inspired by artists but created by them, with signed pieces in numbered editions just like artworks.

The Haspeslaghs dedicate much of their time to tracking the provenance of such jewels and sharing their knowledge. Artist-jewellery collector Diane Venet joined the cause in 2008 by hosting a series of global exhibitions that raised this sector’s profile, and gallerist Louisa Guinness’s 2017 book Art as Jewellery: From Calder to Kapoor was written as an introduction to this area for collectors.

“It is amazing how almost every artist did jewellery,” says Sotheby’s vice-president Tiffany Dubin, who is working on the auction house’s first dedicated sale of artist jewellery (online, September 24-October 4). “When you look at contemporary artists, they tend to make things big to make an impact; it’s very different for an artist to make something small and have the same power.”

The Art as Jewelry . . . Jewelry as Art sale is pitched as sitting in contemporary art, rather than jewellery, and will feature pieces from artists including Max Ernst, Louise Bourgeois (whose spider brooches now change hands for hundreds of thousands of dollars), Niki De Saint Phalle and brothers Giò and Arnaldo Pomodoro.

Jewellery made by today’s contemporary artists in collaboration with gallerists is a lively sector of the market, pioneered by Guinness. “I thought, ‘God, there’s a gaping hole here — there’s none of today’s artists,’” she says about curating her first artist-jewellery exhibition in 2003. “Being married to an art dealer [Ben Brown] and being surrounded by artists, I thought, ‘I’ll fix that.’” After 20 years as a physical gallery in London, Guinness has moved online since May, with a small private space by appointment only.

Over the years, Guinness has forged partnerships with many stars of the contemporary art world, including Grayson Perry, David Shrigley and Sue Webster to create pieces, as well as building a formidable collection of jewels on the secondary market both for herself and for sale, with a focus on Calder and Lalanne.

A recent successful collaboration was with Tarka Kings, who she helped translate her precise drawings and cut-paper works into linear gold jewels. “If you know her work, they are very identifiable,” says Guinness. “That’s something I always say to the artists — don’t lose your identity [when making jewels].”

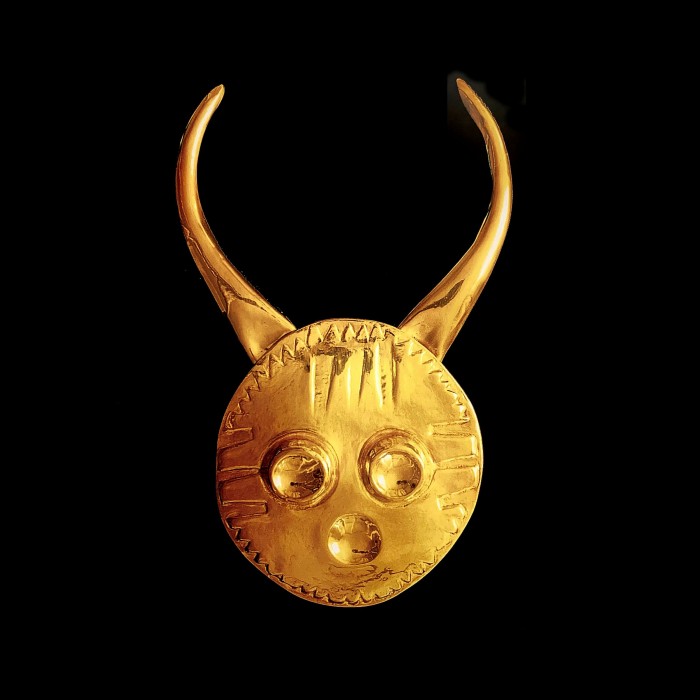

Cipriani, who once worked with Guinness, has also gone down this route. In a 2018 collaboration with Ai Weiwei, the artist continued his research into human migration, as seen in his 2017 Human Flow documentary on the refugee crisis, by producing a 24ct gold ring. It was decorated with hieroglyphic-style figures depicting families walking with bags, fleeing refugees crammed on boats, armed soldiers, barbed wire. The rings start at €70,000 and Cipriani points out that you’d be unlikely to acquire an artwork of his in another medium for that price.

“I believe there is a hunger out there for these works,” says Dubin, whose Sotheby’s sale will include new pieces such as sculptor Tom Otterness’s first jewellery in 18ct gold. “People who maybe wanted an Anish Kapoor but a miniature version. Louise Nevelson [jewellery is] something they can put on their coffee table and wear out. These are for intelligent collectors who . . . have got all the brands, but this is another category they can move into and understand because they know the artists.”

With skyrocketing prices for mainstream contemporary art leaving many collectors empty-handed, it is easy to see that this emerging — though very much not new — medium has a long way to go yet.

Comments