ETF tax advantage feared at risk if Democrats win Senate

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Interested in ETFs?

Visit our ETF Hub for investor news and education, market updates and analysis and easy-to-use tools to help you select the right ETFs.

Holders of US-domiciled ETFs might have been enjoying a post-election market rally, but they face a sting in the tail if the Democrats manage to win control of the Senate in January's run-off elections.

Some experts believe that if the party gains a majority in the upper house it will seek to revoke a capital gains tax exemption that currently gives ETFs an advantage over mutual funds.

“We are hearing conversations out of [Washington] DC,” said Robert Tull, president of Procure Holdings, an ETF industry veteran.

“There are a group of people who are looking at eliminating the in-kind and creation and redemption advantage. They think that somehow ETFs are avoiding tax, which they are not.”

Jon Burckett-St Laurent, senior portfolio manager at Exencial Wealth Advisors, said he took the risk “seriously,” with recognition of unrealised capital gains in ETFs one of several potential tax increases, which “would be a headwind for the markets”.

Mutual funds’ capital gains tax liability stems from their need to engage in “cash” transactions. When investors want to sell their units, the fund sells a slice of its underlying holdings. If these holdings have appreciated since the fund purchased them, a capital gains tax liability is triggered for the fund and all of its investors, even those who are not redeeming.

This liability can also be triggered whenever the fund manager makes changes to the underlying portfolio.

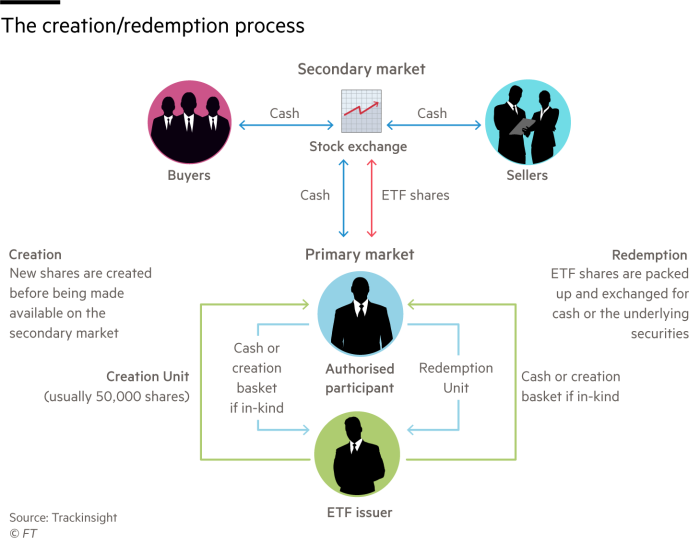

In contrast, when faced with redemption requests, ETFs do not unusually need to sell their underlying securities. Instead, they can deliver baskets of stock “in-kind” to their authorised participants, the large banks that create and redeem shares in ETFs.

As a result, the trading activity, and any resultant capital gain, occurs outside of the fund so there is no pass-through to the end-investor.

Moreover, since most ETFs passively track their underlying index, they also typically trade less than mutual funds, which unlike ETFs are actively managed, limiting portfolio turnover.

All this can make a meaningful difference. ETFs can still be liable for capital gains in unusual circumstances, for example if they need to drastically rebalance their portfolio due to substantial changes in their underlying benchmark, while leveraged and inverse ETFs generally cannot make use of in-kind transactions.

However, research by Morningstar in 2018 found that over the previous five years, on average, less than 6 per cent of US-domiciled equity ETFs paid capital gains to shareholders, compared to 58 per cent of comparable mutual funds.

In addition, the average five-year capital gain for the ETFs was 0.86 per cent of net assets, versus 1.45 per cent for mutual funds.

Some capital gains distributions can be larger still. Christine Benz, personal finance director at Morningstar, said mutual fund payouts might be particularly chunky this year, due to strong performance as well as redemptions by investors who are increasingly switching from mutual funds to ETFs.

ETF screener

Interested in finding out more? Our ETF Hub means in-depth data, news, analysis and other essential investment information is only one click away.

Some funds managed by the likes of Columbia Threadneedle, Invesco, JPMorgan and T Rowe Price will make distributions equivalent to double-digit percentages of their net assets, Ms Benz said, with one AMG fund making a “whopper of a distribution” of 27-33 per cent of NAV.

“It’s long been a complaint [of mutual fund managers] that ETFs have this advantage and it’s one reason why they are lower cost, as they have a lower tax burden. It’s a material saving,” said the head of regulation at a US bank.

“Congress is looking at it as tax avoidance because the mutual funds are crying about this because they are creating the gains within the fund,” said Mr Tull.

The differential tax treatment is likely to become more prominent irrespective of the changing political backdrop due to the rise of active ETFs, which almost inevitably trade more than passive funds, magnifying the benefit of trading occurring outside the fund.

Indeed, some analysts believe the differential tax treatment is one reason why so many US fund managers are launching active ETFs.

Mr Burckett-St Laurent argued that “the middle of a global pandemic” was not a good time to be making regulatory changes “that would have unknown effects”, so any rewrite of taxation was perhaps unlikely before 2022, “but there is nothing to say they won’t do it immediately”, he added.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments