Silverlens gallery offers stateside visibility to south-east Asian artists

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As blue-chip American galleries continue to expand into Asia with outposts in Hong Kong, Taipei and Seoul, Silverlens has headed in the opposite direction. Closely watched by collectors and curators in east and west alike, the Manila gallery, which focuses on contemporary artists from south-east Asia and its diaspora, opened a location in New York’s Chelsea neighbourhood last year.

“I love this feeling of being an established gallery and the new kid on the block at the same time,” says Rachel Rillo, who co-directs the gallery with founder Isa Lorenzo. “Everything feels fresh again.”

Now, with five stateside exhibitions under its belt, Silverlens is participating in Frieze New York for the first time, having previously shown in the fair’s London and Seoul editions.

Lorenzo launched Silverlens, which was initially devoted to photography, in 2004. At the time, she had just moved back to Manila after completing a masters programme in media studies at Parsons School of Design in New York. As a photographer herself, she was looking for a gallery to show her work. “I found that the gallery system in Manila then was unstructured, informal and lacking sustained partnerships,” says Lorenzo. “So I opened my own gallery in my apartment — and it’s the only job I’ve had since.”

In 2007, after relocating Silverlens to a former piano factory, Lorenzo invited Rillo, a photographer who had recently returned to Manila after studying at the Academy of Art in San Francisco, to join as her co-director. The pair broadened the gallery’s programme to encompass works across media, from Pow Martinez’s crude, satirical paintings to found-object assemblages by Pinky Ibarra Urmaza that reference the experience of immigrant children seeking legal sanctuary.

Lorenzo and Rillo had already tried their hand at expansion in 2012, opening an outpost at the Gillman Barracks art complex in Singapore. Three years later, Silverlens was one of five galleries that left the site because of lacklustre sales and foot traffic. “After a while, the Singapore audience was less engaged — and that’s partly because we weren’t working with artists on the ground there,” says Lorenzo. “In New York, we will present a mix of our core artists from Asia as well as more local artists that fit our programme.”

Lorenzo recalls feeling “absolutely invisible” during her earlier years in New York. “People only had the vaguest idea of what the Philippines was, and nobody cared,” she says. But by 2020, Rillo began to notice that visitors to the gallery’s website were mostly coming from the US; meanwhile, curators from US institutions were expressing interest in the gallery’s artists and programme. The pair spent a month in New York in the summer of 2021. “We saw for ourselves how the Black Lives Matter movement had created huge cracks in the cultural fabric that were enabling other people of colour to enter the conversation,” says Lorenzo.

A ground-level space on West 24th Street, nestled between Lehmann Maupin and Marianne Boesky Gallery, became available in January 2022 and in September of that year Silverlens opened its New York outpost. The inaugural display featured Filipina artist Martha Atienza’s silent videos exploring the impact of the tourism industry in the Bantayan archipelago, along with Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann’s woven mats — made collaboratively with Sabahan craft communities — and photographs partly inspired by the weavers’ stories.

The opening was a bustling, exuberant affair. At the event, Lorenzo recalls, one visitor “gave us both a big hug and said, ‘This is it. This is gravity. This is where people will come to see themselves and be represented.’” That man was Rio Valledor, the son of Leo Valledor (1936-89) and the stepson of Carlos Villa (1936-2013), two significant Filipino-American artists based in the San Francisco Bay Area. The conversation continued and in January 2023 Silverlens announced representation of both artists’ estates; in Villa’s case, representation is shared with San Francisco’s Anglim/Trimble Gallery.

For Frieze New York, Silverlens is giving over the entirety of its booth to Villa’s work. An artist, activist, curator and longtime professor at the now-defunct San Francisco Art Institute, Villa began his art-making career as a minimalist sculptor. In 1969, after a stint in New York, he returned to San Francisco. Influenced by the political currents of the Bay Area, as well as access to ethnographic museum collections, he began to reference non-western, multi-ethnic traditions in his work and more overtly grapple with issues of identity, exploring the power of self-determination and the aesthetics that arise from identity “creolisation”. Villa’s diverse output spanned sculptures, drawings, paintings, prints, photographs, performances and garments; he also produced exhibitions, publications, and symposia that celebrated multiculturalism and highlighted historically marginalised artists.

“On top of all of the things that make Villa important to artists, and a lot of Filipino-American artists in particular, the timing is also right for a general audience to see his work,” says Rillo.

The Frieze presentation, which highlights works made from the 1970s into the 1990s, opens a window on to Villa’s varied practice. Vibrant paintings incorporating prints of the artist’s body are juxtaposed with looping, labyrinthine drawings. “Kite God Coat” (1979), a cornerstone of the booth, is a cloak that Villa made using paper pulp and feathers taken from roosters and pheasants; the regal cape, which was made to be suspended rather than worn, has a lining painted with handprints. Another key work, “American Immigration Policy” (1996), is a door covered with black feathers. The sculpture references the racist history of immigration policy in the US and likely nods to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, an anti-discriminatory federal law that enabled an influx of Filipino immigrants.

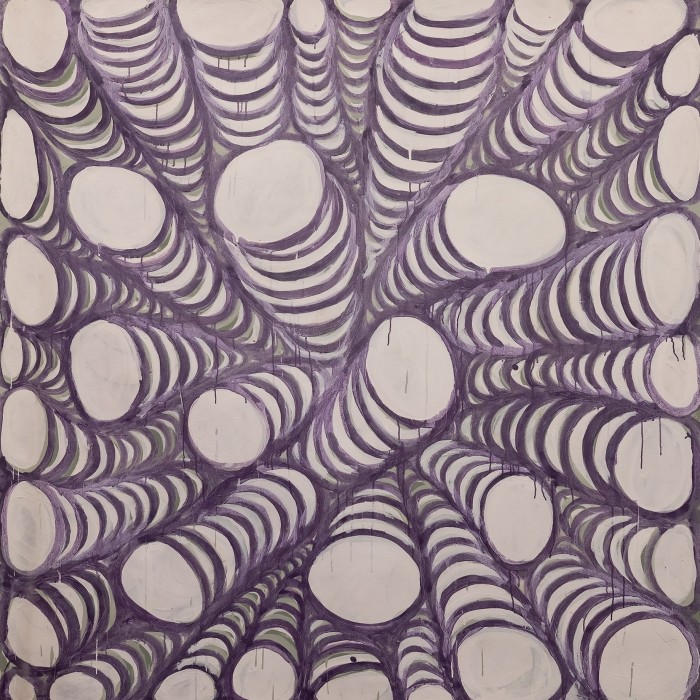

In the Manhattan gallery during the fair, Silverlens will mount an exhibition of “brick paintings” by the Manila-based transdisciplinary artist Maria Taniguchi — part of a larger body of labour-intensive monochromes, made up of rectangular cells, that have occupied Taniguchi for the past 15 years. Figure Study will be her first New York solo show.

“What’s true of Maria is true of a number of our artists: though they have had major exhibitions elsewhere, they are not yet well known in the United States,” says Lorenzo. “That’s something we hope to change.”

Comments