Meet the unsung stars of American fashion

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

What does America look like in 2021 – and who defines what’s on its back? It’s an interesting question, generally because of the fragmented sense of identity evident in many nations – not least the UK, divided down black-and-white lines of pro- or anti-Brexit, or indeed to vaccinate or not to vaccinate. But America, especially, has undergone profound upheaval of late – ideologically, but with an inescapable aesthetic echo.

That is, at least, the thinking of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose latest Costume Institute show, titled In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, is focused on “how fashion reflects evolving notions of identity in America”, according to the museum’s director Max Hollein. Coinciding with the Costume Institute’s 75th anniversary – and also, of course, 20 years since the 9/11 attacks – the exhibition is the first part of a double-header; the second, titled In America: An Anthology of Fashion, will open next May. The latter is a sweep through three centuries of American fashion history, the former a survey of the United States right now “to re-evaluate commonly held assumptions about American fashion”, according to curator Andrew Bolton. “Complicating and problematising” are also his unexpected descriptors for this show.

American style is fixed in the public eye – and it isn’t complicated or problematic. It’s somewhere between Jackie Kennedy in 1963, bloodstained and bouffant in a spare Chez Ninon copy of a Chanel suit, and surly near-naked mid-1990s teenagers dressed in Calvin Klein jeans. Halfway, there’s a trip to Studio 54, to Liza Minnelli in the Halston jersey so recently highlighted via Ryan Murphy’s Netflix mini-series and referenced by Tom Ford at Gucci 25 years ago, and in his eponymous line for the past decade. (Ford also owns Halston’s old Upper East Side home.)

Those clothes are united by what, universally, is seen as “American” in style: simplicity, easiness, freedom, democracy. Those tenets have typically held up the pillars of American fashion and the designers we know on a first-name basis: Donna, Calvin, Ralph. Denim is worn by everyone, from blue-collar workers to the president; Andy Warhol even wore Levi’s under his tuxedo trousers when he went to the White House.

Until recently, American fashion meant sportswear, profitable jeans lines and no-fuss eveningwear that, more often than not, looks like T-shirts or vests elongated in cashmere or spangled with sequins. Today, however, American fashion – like American culture – is more complex, more fractured, than any time before. And outside of the aforementioned trinity of mononymous mega-brands is a network of under-appreciated, oft-overlooked designers whose groundbreaking work has helped shape global style, not just that of the US. Their work has been even further illuminated by recent movements such as Black Lives Matter, which gained a new international prominence in 2020 and is still reverberating internationally, and which has allowed many talents to be retrospectively reassessed.

Stephen Burrows is a prime example: he pops up in the Netflixed story of Halston as one of five names to be shown at the famous Battle of Versailles in 1973, in which the US “sportswear” designers were pitted against the reigning French talent of the day. The same year, he also became the first black designer to win a Coty award (once known as fashion’s Oscars, and which have now been replaced by the CFDA Awards). Burrows, who is about to turn 78, is still creating – a black designer in a global fashion industry where that remains a comparative rarity. His work is still disco-infused, colourful and energetic, in bright jerseys wrapped and draped sensuously around the body – ideal for dancing.

Likewise, Patrick Kelly, who in 1988 became the first American – and first person of colour – to be officially embraced by the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode and to show officially in Paris. He died in 1990 of complications from Aids, but his designs were focused on inclusivity decades before the notion became a buzzword. Kelly’s clothes were, ostensibly, light-hearted and witty, but his African-American heritage was at the forefront of his work: he appropriated racially charged imagery – of “blackface” dolls, watermelon wedges and the banana-frill skirt worn by Josephine Baker when dancing at La Revue Nègre in 1926 – and used it to symbolise black pride as opposed to oppression. His vision was innately American: freedom, again.

If those two names were early vanguards of change, today we are seeing stereotypes of American fashion well and truly shattered. “American fashion is undergoing another renaissance,” says Bolton. Modern fashion influences include names diverse and unexpected. Prabal Gurung, for instance, a Nepalese designer who has dressed Oprah Winfrey, Michelle Obama and Priyanka Chopra. Or Christopher John Rogers, a rapidly rising black talent whose clothes were worn by vice-president Kamala Harris to the inauguration.

Others, however, are less familiar to many outside of the inner circle of the fashion industry. I’m thinking of labels such as Vaquera, a young design duo – Patric DiCaprio and Bryn Taubensee – whose clothes are cartoony and celebratory, often complicated, never boring. They’ve made dresses out of sofa-sized Christmas present bows, giant Valentine’s chocolate boxes or hundreds of fake credit cards (that one was left in a taxicab the night before a show, and had to be entirely remade). They were featured in the 2019 Metropolitan Museum of Art show, inspired by camp, via a minidress resembling a Bunyan-esque jewellery pouch in Tiffany blue, which reputedly arrested the attention of the designer Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, whose Dover Street Market retail empire is now in partnership with the business. Their clothes are fantastical and about as far from simple sportswear as you can get. Vaquera are fantasists in the vein of American greats such as Cecil B DeMille rather than Tommy Hilfiger. “We’re disappointed with the reality of fashion – especially in New York,” says Patric DiCaprio. “It’s not Unzipped.”

He is talking about the 1995 feature documentary charting the creative process behind the collection of former New York fashion darling Isaac Mizrahi. Supermodel-heavy, Technicolor and glamorous, it’s the best film about fashion ever made, quite possibly. Yet Mizrahi went bust in 1998: he currently does one-man cabaret shows. Vaquera loves unsung or forgotten fashion heroes like him. In 2018, the trio created T-shirts printed with the faces of their favourite fashion designers, including cult New York figures Miguel Adrover and Andre Walker. Adrover, a friend of Alexander McQueen, was a hot ticket circa 2000. In 1999, he made a suit from the cotton fabric that had covered the mattress of his recently deceased neighbour Quentin Crisp. He also showed shredded “I Love NYC” T-shirts and an inside-out trench coat by Burberry, who threatened a lawsuit. Endlessly referenced – ironically, by fashion brands including Burberry – Adrover has since retired from fashion, moved into the art world and is now based in Mallorca.

But Andre Walker is still creating in New York. Another in a small pool of black designers, he first showed at a Brooklyn nightclub in 1981, when he was 15. The Metropolitan Museum show features his 2017 collection titled Non-Existent Patterns, based on garments originally designed between 1982 and 1986, when he was still a teenager. His clothes, then and now, look like nothing else. Now aged 55 he is one of the fashion industry’s greatest unsung heroes, who has quietly consulted with designers such as Kim Jones, and with Marc Jacobs when he was artistic director of Louis Vuitton.

“It’s an undeniable truth that American fashion is about something not fussy,” says Walker. “That classicism, that purity and that utilitarian spirit is really what I associate with American fashion.” It’s something you can associate with his clothes too: many freely cut (as the name of that collection suggests, without traditional dressmaking patterns), fabric pinned and draped around the body in a remarkable display of technique. His 2017 show featured clothes made from hardy Pendleton blankets – another reason for their inclusion in a show about America, besides Walker’s enormous talent.

Yet for Walker, American fashion is changing – or, rather, has changed. “I think American fashion has always been influenced by whatever was going on in Europe,” he says. “Now American fashion, or fashion that’s taking place in America, is actually starting to parallel Paris. Becoming a hub, where lots of different types of designers can actually thrive.”

He cites a few designers whose work he is excited by: the young Central Saint Martins graduate Conner Ives; the label Puppets and Puppets, designed by fine artist Carly Mark; and an upstart label called AREA, whose clothes are flashy and decidedly non-binary. “Those clothes are really exciting,” says Walker. He seems surprised, as many in the fashion industry have been, by the recent resurgence of new New York talent superseding our minimalist memories of Donna, Calvin and Ralph. Worthy of a museum show? Probably. And hopefully, unlike so many past talents, they’re here to stay and be remembered.

Christopher John Rogers

The Louisiana-born designer established his label in 2016 and is renowned for his vibrant, maximalist designs, which have been worn by Lady Gaga and Tracee Ellis Ross.

Stephen Burrows

New York-based Burrows was a fixture of the disco era, clothing patrons of Studio 54 and Le Jardin in “lettuce hem” dresses and sequins.

Vaquera

Founded by Patric DiCaprio in 2013, the brand is known for its “anti-establishment” sentiment and off-kilter collections. It’s now run as a collective, designed by DiCaprio and Bryn Taubensee.

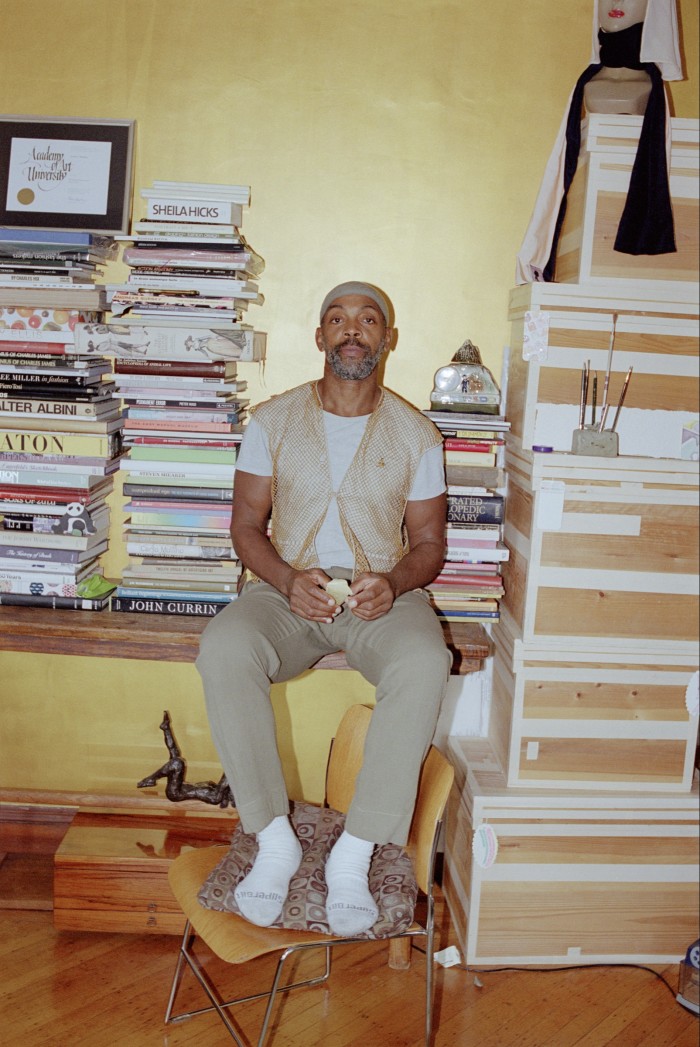

Andre Walker

The Brooklynite first rose to fame in the ’80s and has been designing and consulting, on and off, for the past four decades.

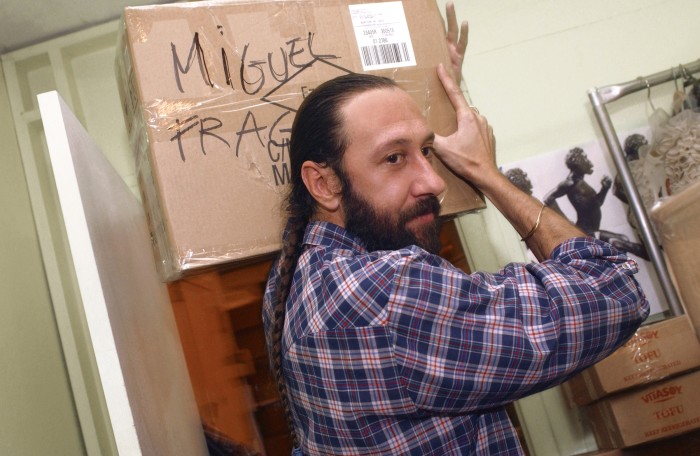

Miguel Adrover

The Majorca-based designer was the toast of New York’s fashion scene in the early 2000s – his celebrated designs included a blue shawl emblazoned with the United Nations logo.

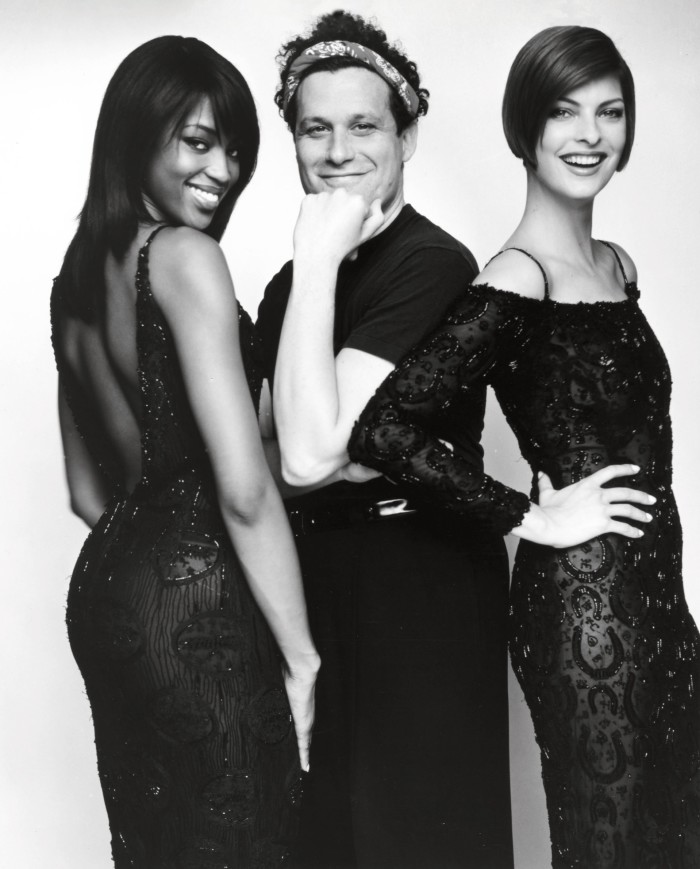

Isaac Mizrahi

Now perhaps better known for his TV appearances than his collections, Mizrahi was celebrated in the ’80s and ’90s as a designer, winning the CFDA Award for womenswear twice and dressing Nicole Kidman and Julia Roberts for the red carpet.

Patrick Kelly

The Mississippi-born designer was revered for interlacing his figure-hugging and exuberant collections with radically charged symbolism celebrating black heritage and cultural identity.

Comments