Whatever happened to the global savings glut?

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

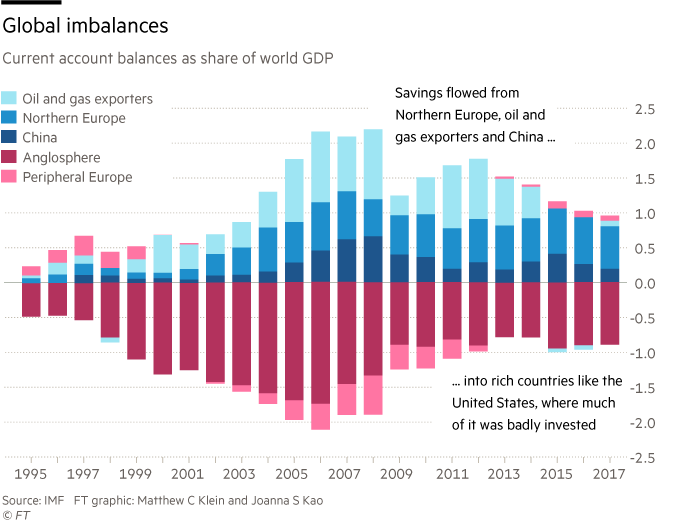

Cross-border lending helped facilitate the credit crisis a decade ago. After the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, many countries in that region decided that maintaining big foreign currency reserves was a prerequisite for financial stability. They sold bonds to their citizens and invested the proceeds in foreign — primarily US — assets. Another stream of money came from Germany, where post-unification wage reforms and European monetary policies created an exporting powerhouse. Still another came from the oil exporters, awash in petrodollars. These flowed towards America, too.

The money washed up in the US housing market, driving up investment and prices. The price appreciation led to a lively asset securitisation market. The rest is history.

Since the crisis, low oil prices have eliminated a big part of the glut. The German and Chinese contributions, which fell after the crisis, are approaching 2007 levels again. But it is not America’s current account deficit that looks scary now — that dubious honour goes to some emerging market countries and oil producers such as Saudi Arabia.

How far can the financial crisis be blamed on a global savings glut, and is the world economy in healthier shape today? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Comments