Brussels clamps down on ‘greenwashing’ in bond market

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The EU has drawn up a set of standards to fight “greenwashing” in the bond market, the first step towards regulatory oversight for a fast-growing asset class that has so far largely governed itself.

The deal reached late on Tuesday night between the European Commission, parliament and member states could eventually lead to a sharp reduction in the volume of debt allowed to carry a sustainable label, say analysts.

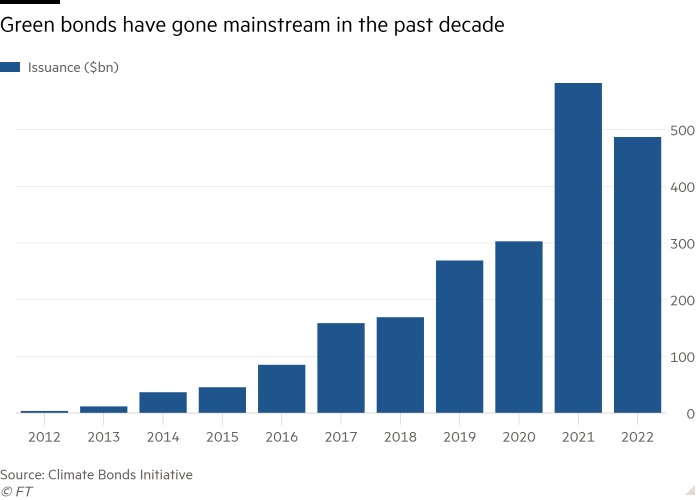

Issuance of green bonds, a class of debt whose proceeds are earmarked for climate-friendly spending, has mushroomed in recent years — particularly in the EU — as investors clamour for assets that align with their environmental goals. But the rapid growth has sparked calls for increased regulation and a common standard, to clamp down on greenwashing, where dirty industries raise cash to fund a small part of their activities without changing their overall environmental impact.

Only a “minority” of the $500bn of green bonds issued last year would qualify for the new voluntary label, Paul Tang, a leftwing Dutch MEP who led the parliament’s efforts to reach a compromise, told the Financial Times.

“I see green bonds issued for airports in Mexico, it’s exactly what we don’t want to have,” he said. “With a clear system for disclosures, any green bonds not using this system will probably be looked at with increasing suspicion,” he added in a written statement.

Mairead McGuinness, the EU’s financial commissioner, said “the transition to climate neutrality will require a lot of investment, and public money alone is not enough” and that by using the green bond standard “issuers can demonstrate their green credentials and offer investors certainty about where their money will flow”.

A spokesperson for the European parliament described the deal as “a new standard to fight greenwashing in the bond markets”.

To be labelled “green” under the new rules, 85 per cent of the funds raised by the issuance must be allocated to activities that align with the EU’s taxonomy, which defines sustainable investments within the bloc.

Issuers will also have to disclose how these activities will help the company’s overarching climate transition plans.

The standards are part of a wider push by the EU to counter greenwashing. The bloc’s three financial regulators launched a joint call for evidence on greenwashing in November in a bid to crack down on inflated marketing claims. The European Commission will present further legal proposals governing consumer products this month.

Some investors fear that compliance with the new rules will shrink the universe of securities available to green bond funds to a tiny proportion of the overall market. The taxonomy is seen by many as an unwieldy and complex list discredited by its inclusion of certain gas and nuclear-related investments.

Less than 3 per cent of global economic activity is aligned with the taxonomy, according to a report last October by the EU’s Platform on Sustainable Finance.

David Ballegeer, a partner focused on sustainable debt at the UK law firm Linklaters, described the taxonomy as a “straitjacket” that would be difficult for issuers to comply with in its current form. But the EU’s green bond label would be easier to obtain from 2026, he said, when all listed companies and other large companies must start publishing their share of taxonomy-aligned activities and investments.

EU countries had pushed for more flexibility on alignment with the taxonomy, Tang said. The deal on green bonds reached on Tuesday must still be approved by member states’ ministers and the European parliament.

Sean Kidney, head of the non-profit Climate Bonds Initiative, said he welcomed the new rules, but also warned that very few bonds would qualify for the new label until the EU clarifies its classification of what is green. The taxonomy was “Eurocentric and narrow” and “not fit for purpose at the moment”, he said. “Whatever we do, we have to be sure we build on the success [of green bonds] and don’t kill the goose that laid the golden egg,” he added.

In the absence of regulation, index providers have so far relied on screening by groups such as the CBI to decide what to include in green bond indices. Last year the CBI drew attention to issuances it did not consider to have positive environmental and social impact, including a two-part $1.6bn issuance by the US utility company Consolidated Edison, which planned to use some of the cash to invest in gas meters.

Other jurisdictions have already sought to clarify rules of engagement around green debt. China’s central bank backed the publication of voluntary standards for green bonds last year, stipulating that all of the proceeds raised should go towards projects defined as green in either its own or foreign taxonomies.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments