Tana French: ‘I love the small, odd things that were part of people’s daily lives’

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It might have started when I was about five, digging in our back garden. The hole was knee-deep when I found a smooth, teardrop-shaped piece of emerald-green glass at the bottom. I remember rubbing it on my shorts to get the mud off and staring at the thing, enthralled. I had no idea what it was – in the end I decided it was probably an arrowhead. (It’s definitely not an arrowhead.) That didn’t even really matter much to me, though. The part that fascinated me was that it had belonged to someone else, someone who had stood where I was standing and who was gone now, someone who would always be a mystery to me, because I had no way of connecting to them – except through this unexpected little thing in my hand.

I’ve still got the green glass thing, which probably fell off a piece of costume jewellery, and I’ve been collecting scraps of the past ever since. Some of them were passed down from various relatives – I’ve got a dolls’ chest of drawers that was made for some great-great-great-grandmother in 1847, and a pair of minuscule dolls’ opera glasses that belonged to some ancestor – if you peer into them at just the right angle you can see a picture of a cathedral. Others I picked up at antique fairs or on eBay: a Viking belt chape, a vesta case with an engraving that says it was a souvenir of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Adelphi Theatre in 1906, a firebrick dated 1606 with carvings of what look like deer with wings. Some of them I found: I’ve got a bunch of shards of pottery from various eras, including a handful of Edwardian ones that came out of our garden when my kid followed in my footsteps by digging a really impressive trench.

Almost all my old scraps fit in my hand. The big valuable antiques, ornate furniture and fancy ball jewellery don’t do anything for me. The ones I love are the small, odd things that were part of people’s daily lives – an Edward I penny, a couple of Tudor clothing hooks, a handful of old clay marbles. And almost all of them are worth only a few quid, because I don’t want the ones that are in mint condition the way serious collectors do. I’m not after the things that have been kept reverently in display cabinets. I like the stuff that’s worn and battered, that’s been used and taken for granted, maybe broken and mended along the way. I use as many of my bits and pieces as I can. We keep coffee pods in a Victorian marmalade jar. For a while one of the clothing hooks was my key ring, but it kept catching on my pockets.

These little antique scraps each serve as a tiny defiance of time. The “C Hopson” who used an engraved silver thimble is long gone, but the fact of her existence is vivid in my mind whenever I darn anything. Wearing a locket brooch made from a first-world-war army button, or a 17th-century poesy ring, is like looking at cave-art handprints: it’s a recognition that some unknown person was real and alive, once, and a fragile link to them across all those years.

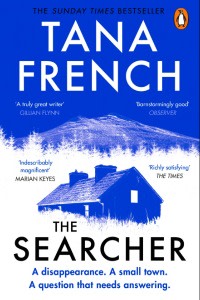

The Searcher by Tana French is published by Penguin at £8.99

Comments