Mino Raiola: meet the super-agent behind Pogba and Ibrahimovic

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If you had to guess Mino Raiola’s job from his appearance and clothing, you would say: small-town pizzeria waiter on his day off. In fact, Raiola grew up working in his family’s restaurant, and his service remains impeccable. From the moment we meet in his pied-à-terre beneath his parents’ flat, on a drab downtown avenue in the Dutch town of Haarlem, he tries to anticipate my every need. Where exactly would I like to sit? Can he get me an energy drink? Am I too hot with my jacket on?

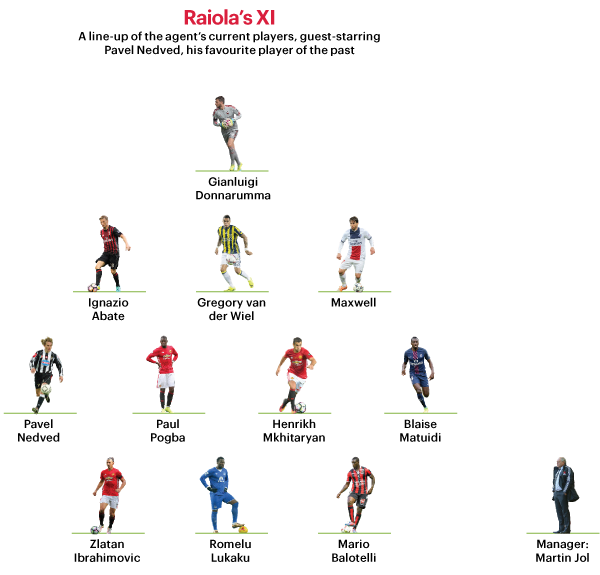

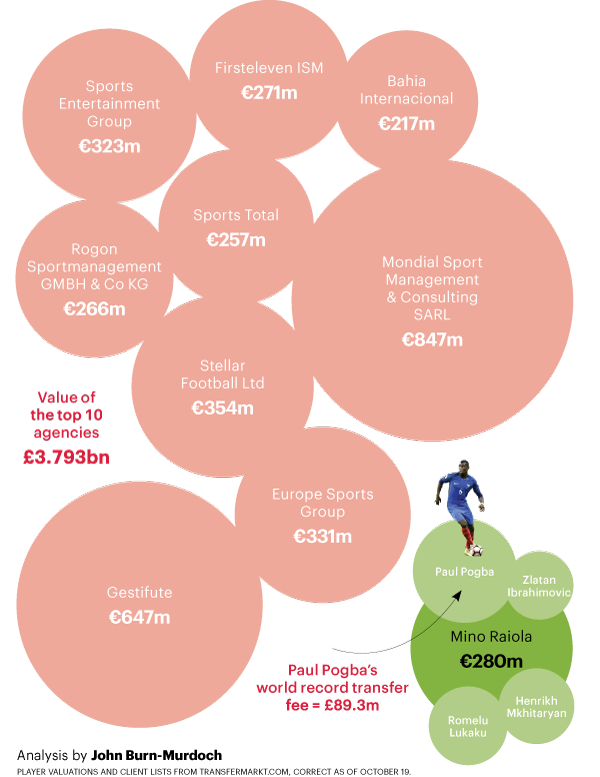

This chubby, bespectacled little Dutch-Italian is arguably the world’s most influential football agent. It’s no coincidence that Manchester United this summer signed three of his clients: Paul Pogba (for a world record transfer fee of £89.3m), Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Henrikh Mkhitaryan. Raiola’s select stable also includes Mario Balotelli, the great unfulfilled talent of the current generation. Like Raiola or hate him (as Sir Alex Ferguson does), he helps shape the transfer market. He is one of the major forces determining which players end up at which clubs.

To help me understand how he learnt his business, Raiola walks me the few hundred yards from his pied-à-terre to the spot where it all began — Haarlem’s beautiful, ancient Grote Markt or “Big Market” square. The family had moved to Haarlem from southern Italy in 1968, when Raiola was an infant. Several branches migrated together; he says about 35 of them lived in three adjoining houses. The Raiolas opened a pizza restaurant, Napoli, on the Grote Markt.

We sink into the outdoor chairs of the Italian restaurant that now occupies the spot. The owner brings me a free espresso, while Raiola surveys his former domain. A passer-by waves and Raiola calls out, “Hey, how’s it going?” — before turning to me and adding, “No idea who that was.”

He reminisces, “My dad worked 18, sometimes 20 hours a day here. At work he is extreme. When I was 11 or 12, I went to work with my dad to get to know him. He was in the kitchen, so what could I do? I could wash up. I still like washing up. It gives me a sort of peace to clean things, to see the instant result of your work.”

Soon, little Mino was dressed in a costume and waiting tables. The work honed his gift for talking to people (generally twice as fast as a normal person). He’d ask customers what they felt like eating, then come up with a personalised menu. If a regular customer was getting divorced, the boy would sit him down for a heart-to-heart. The business model worked: by Raiola’s count, the family ended up with 11 restaurants.

Raiola spoke better Dutch than his father and, as a teenager, was already negotiating with banks for him or popping in on Haarlem’s mayor. He also spoke fluent Italian, or at least Neapolitan. When a restaurant customer complained of trouble with his Italian suppliers, Raiola sorted things out. He founded a company, Intermezzo, which helped Dutch companies do business in Italy.

On the side, aged 19, he became a millionaire by buying a local McDonald’s and selling it to a property developer. After that, he says, he stopped being driven by money. His passion in his scant spare time was football. He had been a decent youth player, and in his early twenties, after dropping out of a law degree, he became technical director of the local professional club, FC Haarlem (now defunct). He developed an audacious plan to sign the brilliant teenager Dennis Bergkamp from Ajax Amsterdam but soon fell out with Haarlem’s other directors — stuffy old conservatives, Raiola thought.

In 1992 Intermezzo helped with the transfer of Dutch winger Bryan Roy from Ajax to Foggia in Italy. Raiola’s personal service included spending seven months with Roy in Foggia, and helping paint the player’s house. While in Foggia, Raiola met his future wife. He also got to know the peculiar world of professional football.

. . .

As an outsider who physically resembled the rotund English fictional character Billy Bunter, Raiola was sometimes snubbed by insiders. He was often asked, “Who are you?” But the disdain was mutual. He recalls: “I was absolutely not impressed.” Many of football’s leading executives had been appointed chiefly because they were clubbable ex-players. “Incest makes that world weak,” he says. “It’s dumb because they want to keep it dumb. It’s a closed world, with gigantic potential, and a huge turnover of money, but often managed by people of whom I think, ‘What the f***?’”

A rare smart executive, in Raiola’s view, was Luciano Moggi. The first time Raiola went to meet him, in the early 1990s, when Moggi was technical director of the Italian club Torino, the appointment was for 11am. Raiola, compulsively punctual, showed up at 10.45am. “I was brought into a room and it was like going to the dentist: there were about 25 people, all smoking and looking at things and talking. At 11.15am nobody had come to me, so I go to the secretary and say, ‘Please can you tell Mr Moggi I’m waiting, and can you tell me how long he will be?’ She looked at me and said, ‘All those people are waiting for Mr Moggi.’”

Raiola, a twentysomething with scarcely any contacts in football, politely informed her he was walking out.

“Two hours later I ran into Moggi in a restaurant. With him was an entourage of those 25 people, who had come out for lunch.” In Raiola’s telling, he went up and had the following conversation:

. . .

Raiola: Are you Mr Moggi? Moggi: Yes. Raiola: I find it very rude that you made me wait. Moggi: Who are you? Raiola: I am Raiola. Moggi: Ah, you’re Raiola. If you’re this unpleasant to me, you will never sell a player in Italy.

. . .

Soon, however, Raiola was selling players in Italy. In Foggia he had got to know the club’s coach, a workaholic Czech named Zdenek Zeman. They had talked football obsessively. One day Raiola told him, “The footballer you want doesn’t exist. That’s the perfect footballer: one who runs 17km a match, dribbles like Maradona, and can train harder than you can imagine.”

But then, in the mid-1990s, through contacts in the Czech Republic, Raiola spotted Zeman’s perfect footballer — another Czech, Pavel Nedved. Raiola today says: “Pavel Nedved is an extremist. The only thing he thinks of himself is that he can’t play football. But he can train harder than the rest.” Nedved would train at his club as a kind of aperitif, and then come home and train much harder in his garden. In 1996, Raiola sold Nedved to Zeman’s new club, Lazio in Rome.

The two Czechs reinforced the lesson Raiola had learnt from his dad: “extremists” succeed. Raiola became one himself. For more than 20 years now, he has travelled around Europe with a small suitcase, working. “It has cost me things,” he admits. “I haven’t seen my children grow up.” He and his family live in Monaco, only partly for tax reasons, he says.

If Raiola ever writes his autobiography (as he sometimes threatens to), he should call it The Art of the Deal. Contract negotiations, he says, are “my matches”. There’s a telling vignette in “Thank You, Mino”, an account by former Dutch footballer Rody Turpijn of his own transfer from Ajax to little De Graafschap in 1998. Raiola and Turpijn went to meet De Graafschap’s chairman in an unsightly motorway hotel. After Raiola’s opening rave about Nedved, which was both heartfelt and a calculated display of status, the chairman jotted down the salary he was offering Turpijn. “Doesn’t look bad,” thought Turpijn. It was more than he earned at Ajax. Anyway, De Graafschap was the only club that wanted him.

But Raiola exclaimed, “Do you know what he earns at Ajax? This isn’t a serious offer. Come Rody, we aren’t going to waste our time.” He got up to leave, so Turpijn dutifully rose too. The chairman pleaded with them to stay. In the next 20 minutes Raiola negotiated a contract (including every imaginable extra) that, writes Turpijn, “largely secured my future. Not only for the four years that I would play for De Graafschap, but just about for the rest of my life.”

The story illustrates one of Raiola’s maxims: even the smallest transfer can change somebody’s life.

Raiola regularly urged Turpijn to be more like Nedved. It didn’t happen: after a disappointing stint at De Graafschap, Turpijn retired from football aged 25, and happily went off to university. However, Raiola’s approach worked on a more ambitious young Ajax footballer he encountered in about 2001 — a Swedish striker of Yugoslav origin named Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

Raiola is a central character in I Am Zlatan, Ibrahimovic’s autobiography. No wonder, because perhaps the key influence on the modern footballer’s career is his agent. The relationship is often closer than the much-discussed but typically transient one between coach and player. This is especially true of Raiola, who keeps his stable of players small so as to offer each one a personal service.

The two immigrant boys met in Amsterdam’s chic Japanese restaurant Yamazato. Ibrahimovic had dressed in a suit. “But who the hell turned up? A bloke in jeans and a Nike T-shirt — and that belly, well, like one of the guys in The Sopranos,” he writes in his book. (Raiola believes that not wearing a suit is an advantage, as it leads people to underestimate him.)

Raiola can do good cop or bad cop, and he knew which one Ibrahimovic would respect. As Ibrahimovic tells it, Raiola disdained the Japanese dishes and, while scarfing down enough pasta for six people, berated the striker for underachievement. He asked Ibrahimovic his standard question for footballers: “Do you want to be the best in the world? Or the player who earns most and can show off the most stuff?” Of course Ibrahimovic replied that he wanted to be the best.

The Swede was impressed. He recounts phoning Raiola afterwards to ask him to be his agent:

. . .

Raiola: [Long pause] All right. But if you’re going to work with me, you must do what I say. Ibrahimovic: Sure, absolutely. Raiola: Sell your cars, your watches, and start training three times as hard. Because your stats are rubbish.

. . .

Soon Ibrahimovic was working like Nedved.

By this time, Raiola’s old enemy Moggi had moved to Italian club Juventus. One day he phoned Raiola to inquire about signing Nedved from Lazio. Raiola recounts the conversation:

. . .

Raiola: Do you have a watch? Moggi: Look, don’t be unpleasant. Yes I do. Raiola: What time are we meeting? Moggi: 12pm, in Florence. Raiola: I’ll be there at 11.50am. But I’m leaving at 12.10pm, and then the price doubles.

. . .

By 12.10pm Moggi hadn’t shown up, so Raiola left. Nedved did end up joining Juventus, and in 2003 won the Golden Ball award for Europe’s best footballer. Now retired, he remains in touch with Raiola. That’s Raiola: close to his players, hostile to clubs and authorities. (Football’s governing body Fifa once fined him for calling its president Sepp Blatter “a senile dictator”, after which Raiola briefly tried to run for Fifa’s presidency.)

Many of Raiola’s players treat him as an all-purpose helpmeet. Mario Balotelli once phoned him to say his house was on fire; Raiola advised him to try the fire brigade. Nowadays Raiola’s younger players FaceTime him. He moves around imitating them as they hold up their phones to show him things they want to buy: “‘I’m walking through the house. What do you think of it?’” He chuckles fondly.

Does he regard his players as friends? “Ninety-nine per cent of them, yes,” he replies.

So he doesn’t see Pogba as a client? “I don’t see him as a client at all. In fact I dare to say, family.”

I suggest that Raiola has turned the model of a family pizzeria serving a clientele of regulars into a football agency. His eyes brighten: “Unconsciously, yes. When you say that I get a little gooseflesh. And it’s true — we didn’t see ourselves as a pizzeria.”

What were you then? “A home. You came to eat at our home.”

His business model informs the layout of his Haarlem workspace: footballers tend to feel uncomfortable in offices, so the place is essentially structured as a kitchen, with a screen in the corner to show matches. On a kitchen rack is a plate inscribed, “Ristorante Napoli, Haarlem”.

. . .

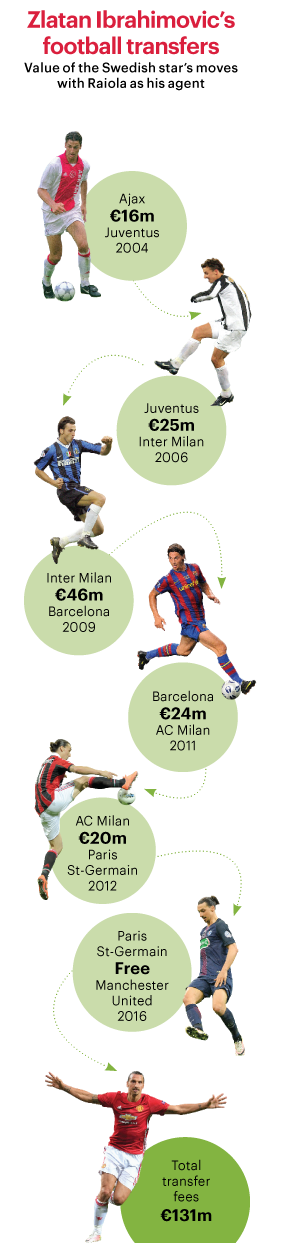

It’s commonly thought that clubs and coaches decide which players to sign. Often, though, the driving force is the agent. Raiola explains, “I always try to formulate a goal with a player: ‘That is what we want. We’re not going to sit and wait and see where the wind blows.’” In 2004 he decided Ibrahimovic should join Italy’s most “extreme” club: Juventus. Dressed in beach shorts and soggy with sweat after an unscheduled sprint through Turin, he did the deal with Moggi for a transfer fee of €16m.

At Juve, Ibrahimovic saw for himself how hard Nedved trained. “I thought you were exaggerating, but it’s true,” he told Raiola. Nedved told the young striker, “You don’t know what you’ve got.” Ibrahimovic merged the Czech’s work ethic with his own superior talent.

The striker’s 15-year European odyssey reveals one of Raiola’s gifts: anticipating changes in the transfer market. Raiola says, “It sounds arrogant. I saw every change in the football world coming before it happened.” In 2006 it emerged that Moggi habitually phoned referees assigned to Juve matches before the game. Raiola realised that Juve would suffer for this. Months before the club was punished by relegation to Italy’s second division, he arranged Ibrahimovic’s transfer to Inter Milan. In 2009 he moved him to Barcelona — a transfer that went wrong when coach Pep Guardiola dropped the player. Any mention of Guardiola’s name still jolts Raiola into almost instinctive tirades (“a coward”, “no balls” etc) but he quickly dispatched Ibrahimovic to AC Milan.

Then, in 2012, Raiola pushed the player out of Italy. “He didn’t want to go at all. But I’d been telling Milan for years, ‘You can’t afford these salaries any more.’” Italy’s football economy was declining, while rich Qataris had bought Paris Saint-Germain. Ibrahimovic reluctantly moved to Paris — where he earned €14m a year in a top-class team while Milan sank.

Ibrahimovic, after 15 years as a Raiola client, is now cumulatively the second-most expensive footballer in history, after Angel Di María. In that time, clubs have paid an estimated total of €131m in transfer fees for the Swede, whose career alone would have been enough to make Raiola rich. When I ask if he takes 10 per cent of a player’s salary, he replies: “Or more, or less. But that is agreed and is very transparent.” However, he insists that he considers money merely a byproduct of good work.

Guiding players’ careers sometimes goes wrong. Raiola’s greatest failure may be the Italian striker Mario Balotelli, who is now with modest Nice, his huge talent unfulfilled. Raiola says that Balotelli has often been distracted from achievement by falling in love: “Balotelli has chosen, unconsciously or consciously, not to put football in the middle of his life. So there were always marginal phenomena that influenced his performances. Zlatan doesn’t have that, Pogba doesn’t, Nedved doesn’t. But Ouasim Bouy [an unfulfilled Dutch talent on Raiola’s rota] doesn’t have that either.”

Does Raiola share some blame for Balotelli’s failure?

“Yes. A big mistake I made in his career was to let him go from Manchester City to Milan, against my advice. I should have said, ‘You succeed with City, that’s it, period. If I’d done that, hard, he would have.”

I suggest that many footballers, possibly including Balotelli, don’t particularly want to reach the top. Why should they? They can make millions without knocking themselves out.

“Well, that’s right,” replies Raiola. “That’s why in my recent conversations I have an important question for players: ‘Why do you play football? What is your drive?’”

What do they answer?

“Well, most haven’t thought about it yet. I send them home saying, ‘Go think about it.’”

A few years ago, Raiola unearthed a French talent with unquestionable drive. Paul Pogba was then a teenage hopeful at Manchester United. He hadn’t broken into the first team and Raiola told him he was underpaid, but added that perhaps he ought to stay anyway, especially as United had a “fantastic manager”, Alex Ferguson. However, in 2012 Raiola asked United for a better contract. He breaks into English to recount the negotiations:

. . .

Ferguson to Raiola: I don’t talk to you if the player is not here. Raiola: Get the player out of the locker room and sit him here. Pogba enters. Ferguson to Pogba: You don’t want to sign this contract? Pogba: We’re not going to sign this contract under these conditions. Ferguson to Raiola: You’re a twat.

. . .

Raiola was unfazed, partly because he didn’t know the word.

. . .

Raiola: This is an offer that my chihuahuas — I have two chihuahuas — don’t sign. Ferguson: What do you think he needs to earn? Raiola: Not that. Ferguson: You’re a twat.

. . .

Ferguson’s published verdict on Raiola: “I distrusted him from the moment I met him.”

Download a high-resolution image of the agents and agencies who run world football

Raiola canvassed Europe’s leading clubs to decide which one Pogba should join. “Juventus said, ‘We want him at any cost. This is the best player we’ve seen in the world.’ However, Juve historically had little patience with youngsters. Raiola told Pogba: “This maybe isn’t a good step for you.” Yet Pogba was set on joining the Italian club.

Raiola says he negotiated a salary that marked Pogba out as a valued first-team player. Afterwards he asked him: “Why did you want to go there?” Pogba replied, “Because in my life I have always chosen the hardest path. This was the hardest path.” He performed brilliantly at Juve, winning four straight Italian titles.

This summer, Raiola brought Ibrahimovic and Pogba to United. Why join a club that hadn’t qualified for the Champions League and has underperformed for three years? Raiola explains, “Because I think: you have go to the club that needs you. This club needed them.”

He had foreseen United’s need as early as summer 2015, when the club signed the young forwards Anthony Martial and Memphis Depay. Raiola claims to have known they wouldn’t succeed. “Not if you have to perform now,” he says, slapping a fat fist into a fat hand. “Martial and Depay come in and say, ‘We have to carry Manchester United, a giant institute?’ So already last year I told the people at United, ‘You’ll have to put in a guy like Zlatan to restore the balance.’ Then the attention goes to Zlatan. He has the experience, and dares take the responsibility.”

And, says Raiola, United needed Pogba too. “Look, Pogba could have gone to all the top clubs. But Real Madrid had just won the Champions League. He’d have been a trophy player there. Barcelona — their three trophies are Messi, Neymar and Suarez. What you see is the final result of years of sculpting. I spent two years working on Manchester United’s deal with Paul.”

United’s decision makers evidently trust Raiola. The coach, José Mourinho, has historically preferred to sign players from his own agent, Jorge Mendes, but now seems happy to work with the Dutchman. Raiola says: “I knew Mourinho from Inter, and there we’d had a bad relationship. I’d said things in the newspaper. But I think Mourinho is intelligent enough to understand what I do. At clubs that understand me, I have three or four players. Now at United, and before at Juventus, Milan, Paris Saint-Germain.” In these cases, says Raiola, he becomes a club’s “in-house consultant”. Logically, then, he must share some blame for United’s current dismal performances.

United paid a world record transfer fee of €105m for Pogba in August. Raiola has said he takes only a cut of his players’ salary — but what about media reports that the clubs paid him €20m, as a percentage of the transfer fee? “I can’t talk about the contract but, in a deal like Pogba’s, it’s not just the clubs who earn from it,” he says.

Were you paid a fee by Juventus?

“No — not in the way that you’re saying it.”

So you did get money from Juventus?

“I have to see how I can phrase this in a way that Juventus cannot tackle me through the law, let’s say. Hmm. How can I say it? [Long pause.] Yes: in this deal Juventus was not the only owner of the player’s rights.”

But third-party ownership of players (TPO) has been banned?

“Not then. Only afterwards [by Fifa in 2015].”

So until TPO was banned, you often owned stakes in players?

“Not often. But sometimes.”

And Pogba was one of them?

“It’s not TPO. Be careful with the legal definition of TPO. But let’s say that in that case there was an upside for our side. And by our side, I mean the player’s side.”

Which isn’t allowed any more?

“It’s not allowed any more.”

Juventus says, “No third party had any ownership of the player’s rights.”

. . .

Raiola boasts of having had great players in every era, and is busily planning ahead. “There are eight, nine players in the Brazilian [youth] team, each one better than the next. I have [Gianluigi] Donnarumma at AC Milan, who’s 17 and is already their goalkeeper. I have a top striker at Juventus, Moise Kean, 16 years old, who might make his debut this year.” Raiola doesn’t sound like a man planning to take up golf.

Many footballers lose all their money after they retire. England’s Professional Footballers Association has estimated that 10 to 20 per cent of ex-players go bankrupt. This is something Raiola thinks about a lot. “Look, you now have players who can earn €50m to €200m [over their careers]. How do you invest that — or not? Players are always getting offers from people.” He puts on an overexcited young voice: “‘Mino, a friend of mine has a real estate company, and they’re going to do this, and I’ll get 14 per cent, guaranteed!’

“But you also have to watch out for banks. Banks want to sell you products too. I now have an [investment] portfolio for various players, which if you add it all up is worth about €900m. And we’re more conservative than conservative. I always say to players, ‘We do not invest.’ We just want the player to finish his career with the money he earned, and more — but not less. What I suggest is, ‘Buy your own house fast, buy bricks, and otherwise keep your money in the bank, even if it’s at low interest. You don’t have to live off the interest. Don’t put it into businesses you know nothing about.

“All my players, in the beginning, want a restaurant, a hotel or a café. I come from the restaurant business and I say, ‘Don’t come to me with that, zero. Because I know what that is.’”

Simon Kuper is an FT columnist

Photographs: Matthew Peters; Raimond Wouda, TT/PA Images; Jacopo Raule; Instagram/Paul Pogba

Comments