Stay on track with your Isa saving

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What relationship do you have with money? Does it love you or leave you? Just like human relationships, some people might feel like they are “soul mates”, yet for others, the answer is “it’s complicated”.

The impending tax year end and rallying cries from financial companies to use or lose your annual Isa allowance provides a useful nudge to evaluate how you and your money are getting along.

We all have different values, priorities and life experiences which influence our relationship with money.

If you feel fearful, scared or overwhelmed by money, you’re more likely to develop ineffective money habits. Common ones are avoiding making financial decisions; holding too much money in low-return assets; coming out of the stock market after a sharp fall; being unable to spend money on the right things; or unable to control your daily spending.

If you recognise yourself, don’t panic. People who feel overconfident about money and their capabilities are not immune to bad habits either. For example, taking investment risks which are unlikely to be adequately compensated by returns or even lead to a total loss of capital. They might feel they have plenty of time and can put off saving for retirement, or tell themselves they will save more when their income has reached the “right” level.

Others might overstretch themselves to buy a home in the hope that it will rise in value — as they have in the past 15 years — only to find it falls in value and they have little surplus income to enjoy life today.

When I was advising clients, I always explained to them that while money means different things to different people, we needed to agree that for planning purposes money meant purchasing power — being able to afford your current and future desired lifestyle until you die. And as we know, that lifetime is getting longer.

If price inflation averages 2 per cent per annum over a 35-year retirement period, your purchasing power would roughly halve over that time. On top of that, we have ever-increasing expectations as consumers. A smartphone is a necessity for most people in the UK now, but no one had every heard of it 20 years ago.

Preserving purchasing power and meeting rising expectations of living standards is easy while you are working and earning, because wages tend to match or slightly exceed price inflation over the long-term. For most, achieving this after you stop work or reduce your earnings will require you to invest beyond cash deposits.

A healthy relationship with money means that you can balance your immediate lifestyle desires with your longer-term needs — the most expensive and non-optional of which is financial independence — and build resilience against future possible financial shocks. It also means that you need to have faith in the future of capitalism to continue to deliver reasonable real returns on your capital.

52a70154-3c52-11e9-9988-28303f70fcffThe amount you regularly add or withdraw from your pot, how you adapt your investment strategy as you build wealth and how you react to market events will all influence whether you have a successful investment experience.

It’s been said that investment markets can remain irrational longer than some investors can remain solvent. As the eminent academic Zvi Bodie says in his 1994 paper On the Risk of Stocks in the Long-Run, equities don’t get less risky the longer they are held. You could argue that the longer the time horizon, the risk — in the form of uncertainty of returns — increases because there are so many events that can happen over multi-decade periods.

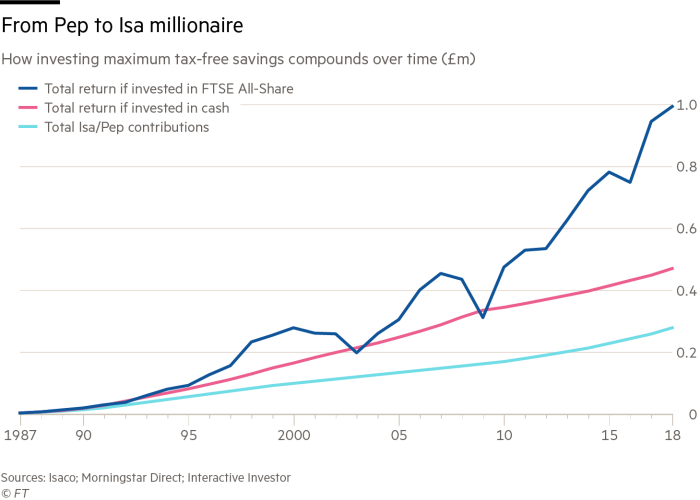

Compounding returns provides some protection against future investment volatility. Albert Einstein allegedly described compound interest as the eighth wonder of the world. Re-investing dividends, interest and capital gains into acquiring more productive financial assets makes a massive difference to investment returns as the chart for the FTSE All-Share index shows.

The longer that returns accumulate, the greater the protection from the inevitable market falls that will happen. And as Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s investment partner, says: “The first rule of compounding: never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

If you haven’t yet accumulated significant financial capital, the amount you add to your portfolio each year will have a greater impact on its yearly change in value than short-term investment returns. This is particularly pronounced in the early years.

For example, if you started to save £250 per month into a stocks and shares Isa, by this time next year you might have some investment growth, but it will be dwarfed by the size of your ongoing contributions. Even after 10 years, new contributions are likely to be responsible for around half the increase in fund value.

It isn’t until year 20 that investment growth contributes the majority — about 75 per cent — of the increase in value. By year 30, investment growth contributes 90 per cent of the increase in value.

What this means for younger people and those with more modest amounts of wealth is that they need to worry less about what investment markets are doing day-to-day, and focus much more on their annual savings rate.

People who have powered themselves to financial independence will tell you that what enabled them to build their wealth was their ability to save as much as possible, as early as they could.

That’s why learning to control day-to-day spending is such an important — and generally under-appreciated — skill to master.

This self-control will also pay dividends later in life. When the time comes to start to taking regular withdrawals from your capital, you will need to focus carefully on the level of income you’re taking. Having some flexibility will minimise the chance of withdrawals exacerbating market falls and extending periods of low returns.

The ancient stoic philosopher Hecato advised “What progress, you ask, have I made? I have begun to be a friend to myself.” In building up and living off your wealth, you are looking for steady progress, not perfection. That way you won’t just be a friend to yourself, but also become soul mates with your money.

Jason Butler is an expert on financial wellbeing and author of “Money Moments: Simple steps to financial wellbeing”; Twitter: @jbthewealthman

Comments