Henry Taylor, Moca LA review — a visionary painter tackles race, brutality and politics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Critics have defined Henry Taylor in myriad ways: activist painter, portraitist, genre painter, outsider, social realist. This insistence on labelling him likely stems from his subject matter’s deceptively straightforward nature: Taylor is best known for portraying African-American figures and his emphasis on the marginalised and the quotidian. But the Los Angeles artist’s sprawling hometown retrospective at Moca, B Side, makes it clear that such broad-brush descriptions overlook the visionary, esoteric and emotive qualities of his work.

Take his earliest series, Camarillo Drawings, portraits of patients who Taylor (born 1958) encountered while working as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital from 1984 to 1995. During those years, Taylor, who as a child had accompanied his father, a commercial painter, on jobs, was beginning to take art seriously as an occupation, earning his BA from the California Institute for the Arts in 1995. These studies, executed in graphite or coloured pencil on sketchbook paper, incorporate fanciful inklings of their emotional states as well as his own. He took ample liberties with hue and form: sallow greens and lurid yellows confer a psychological intensity on the elderly subject of “Catatonic” (1991), ailing yet piercing-eyed, while the man in “Split Person” (1992) has his face horrifically sliced in two, suggesting schizophrenia (per Taylor’s notes).

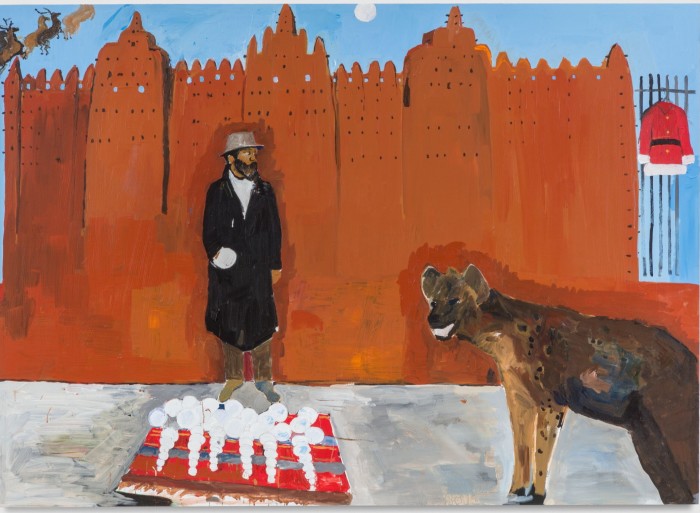

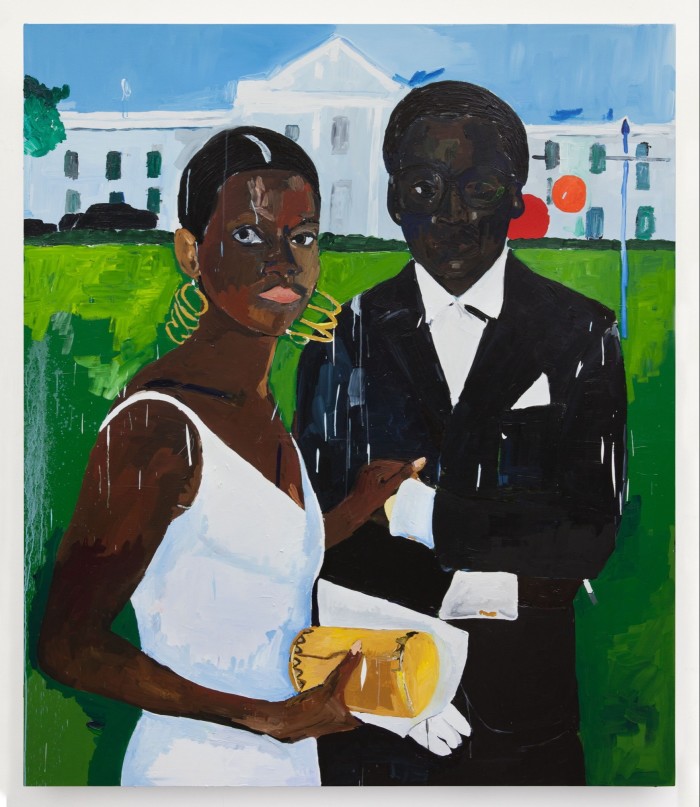

Those early drawings set the stage for the whimsical transformations that have become hallmarks of Taylor’s mature canvases. He revels in painting’s potential for creating absurd juxtapositions, as in “Hammons meets a hyena on holiday” (2016), where a hyena leers at artist David Hammons, selling snowballs against a backdrop of fantastical architecture, or suggesting time-travel in a pieces like “Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas” (2017), where actor Cicely Tyson and musician Miles Davis, painted from a 1968 tabloid photograph, are transposed on to an ostensibly Obama-era White House lawn.

A leitmotif of Taylor’s more traditional portraits is that the eyes diverge in size or angle, as in “My Great Niece Taylor Watson” (2020), or colour, as in “A young master” (2017), a posthumous picture of painter Noah Davis with one iris brown and the other eye partially blue as if with reflected light. These confer a heterogeneity of character akin to that of “Split Person”, only instead of that more directed diagnosis, they might symbolise dual sides of the same personality or different thoughts taking place simultaneously.

He manipulates the body for uncertain, unsettled effects: feet and hands are disproportionately large or small; bodies are skewed; limbs are elongated or even missing, as in “Eldridge Cleaver” (2007), whose legs are curiously curtailed and angular, as though he were becoming one with the chair in which he sits, ruminatively smoking.

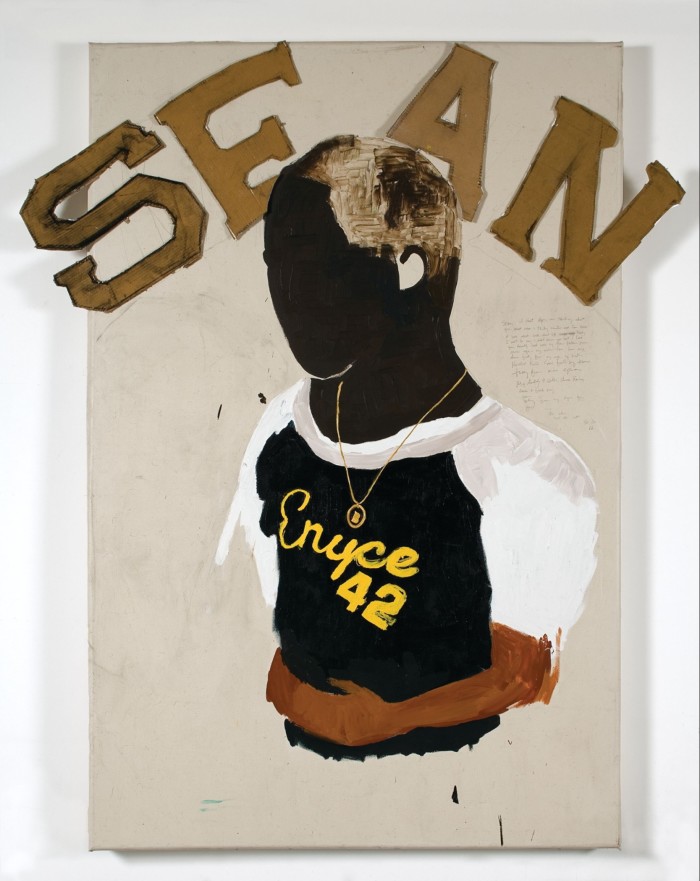

Taylor’s improvisational, expressive brushwork conveys a frenetic sense of flux. He leaves evidence of his process throughout his paintings: ghosts of roughed-out sketches haunt reworked images; unfinished passages are partially painted over; imagery is interspersed with drips, raw canvas, desultory splatters. Heightening the impact are snippets of text, such as a pencil-scrawled sympathy message dedicated to Sean Bell, an unarmed black man killed by police in 2006, in the painting “Homage to a Brother” (2007). It’s easy to see how Zadie Smith, writing for the New Yorker, finds in Taylor’s “restless” style a metaphor for black history, “the way many black people actually experience it: as simultaneous change and stasis, revolution and stagnation, one step forward, two steps back”.

These attributes are enhanced by monumental scale, which sometimes serves to elevate the ordinary and other times forces viewers to confront harsh inequities head-on. The 13-foot-tall painting “The 4th” (2012), its barbecuing protagonist towering over the viewer, her sheer size eliciting a reverential awe, reads as a celebration of underrecognised labour done by black women. By contrast, “THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!” (2017), a stark larger-than-life portrayal of Philando Castile the moment after he was shot at close range by a police officer, provokes a chilling, visceral reaction.

One spacious gallery is occupied by an installation featuring an imposing phalanx of mannequins configured as a Black Panther meeting, surrounded by posters protesting against war, incarceration and racial injustice. Made for this show, the untitled piece is among Taylor’s most explicitly political and is also a tribute to his older brother, Randy, a former associate of the Black Panthers. Here, surreal devices take on an especially disquieting nature: printed photos of faces and eyes of people murdered by law enforcement peer out from buttons pinned on the mannequins’ jackets and from inside a boom box.

Glimpses of Los Angeles, particularly downtown where Taylor’s studio is located, recur throughout his paintings. His version of the city is enlivened by eccentricities, such as a rose floating in the sky above a corner market in “Fatty” (2006). On one untitled 2022 canvas, a colossal second world war plane hovers ominously over a mysterious scene of two men sprinting down an asphalt road in the middle of the city. The streetscape appears quintessentially southern Californian, representing not an outsider’s airbrushed ideal but a gritty, if highly stylised, version of the urban reality lived by many Angelenos.

Even in the most down-to-earth situations, Taylor finds moments of enchantment and eeriness. Take the pensive mien of the man having his hair styled on a stoop in “Gettin it Done” (2016): golden orbs resemble glowing headlights within his irises while his corneas are rosy sunsets of salmon and Naples yellow. An entire world seems to inhabit those eyes, expressing, as with much of Taylor’s work, an expansive reverie within the everyday.

To April 30, moca.org

Comments