The new ‘blood diamonds’: the elaborate plan to halt Russia’s trade

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you’ve worn, touched or seen a diamond which was cut and polished in the past decade or so, the chances are it passed through Surat, India.

India boasts more than 90 per cent of the world’s diamond manufacturing, and this historic trading city on the north-west coast is the industry’s capital.

Surat’s polishers, who sit in cramped offices hunched over abrasive wheels to transform rough rocks into dazzling gems, have won the city its reputation in part by tackling small gems hewn from Siberian mines.

Russia’s tiny diamonds are only cost-effective to manufacture when workers are paid less than in traditional diamond centres like Antwerp, but are favoured by jewellers for ornamentation such as the sides of a glitzy engagement ring.

Ramesh Savaliya thinks about three-quarters of the diamonds he processes in his small polishing business are from Russia, the world’s largest diamond producer. That’s based on what the resellers Savaliya buys from tell him; the stones do not come with paperwork identifying their origin.

That may not be the case for much longer. The war in Ukraine, thousands of miles away, is set to transform Surat’s cutting and polishing industry and reshape the secretive global diamond trade as the west tries to cut off Russia’s diamond dollars.

This month, officials from the world’s seven largest advanced economies, a group known as the G7, are expected to vow to work towards measures on the sale of Russian diamonds in their nations, in a bid to squeeze Moscow’s access to finance, and — they hope — impede the Kremlin’s ability to wage war on Ukraine.

Russia’s rough diamond exports were worth $4bn in 2021, trade statistics show. That’s only a fraction of Russia’s crude oil exports, but every available revenue source is important to Moscow’s treasury as it bankrolls President Vladimir Putin’s invasion.

Russia this year tapped Alrosa, the world’s largest diamond mining company by volume and two-thirds owned by state bodies, for a windfall tax of Rbs19bn ($244mn), forcing it to halt dividend payments.

In the US, the world’s largest market for finished diamonds, the government has already taken action — the Treasury department placed sanctions on Alrosa in April 2022, and President Joe Biden banned the import of Russian rough diamonds. The EU did not follow suit, however, as Belgium resisted restrictions that could hurt its diamond trading industry in Antwerp.

But soon, G7 capitals will join Washington by endorsing efforts to drive down Russia’s diamond mining revenues, according to a draft communique seen by the Financial Times, aiming to introduce an effective mechanism for tracking and tracing individual gemstones — which today does not exist.

Their hope is this would pave the way for the EU banning Russian diamonds, with Antwerp more comfortable with an inspections regime that would not simply divert gems to other diamond hubs, and the US tightening up its own sanctions.

If the G7 settles on a workable scheme, customs border control in western nations will need a declaration of where any incoming diamonds originally came from — although what that exact paperwork would be is still undecided.

However, it would be a sea change from today, where customs officers only require a government-issued certificate guaranteeing that the stones meet the requirements of the UN-backed trade regime called the Kimberley Process, which prevents the sale of diamonds mined in war zones and used to fund insurgencies.

Washington intends for this traceability initiative to outlive the Russia-Ukraine war and any related lifting of sanctions, according to diamond industry executives who have been consulted by western officials. If successful, it would in effect extend the concept of “blood diamonds” to gemstones used to bankroll state-backed warfare, as well as rebel activity.

It could also strangle the diamond industry, say those who work in it. More than a dozen people involved in the trade, from mining to international dealers and Indian polishers, expressed anxiety about how a lasting, unwieldy effort to throttle a relatively minor cash stream for Russia would threaten their livelihoods.

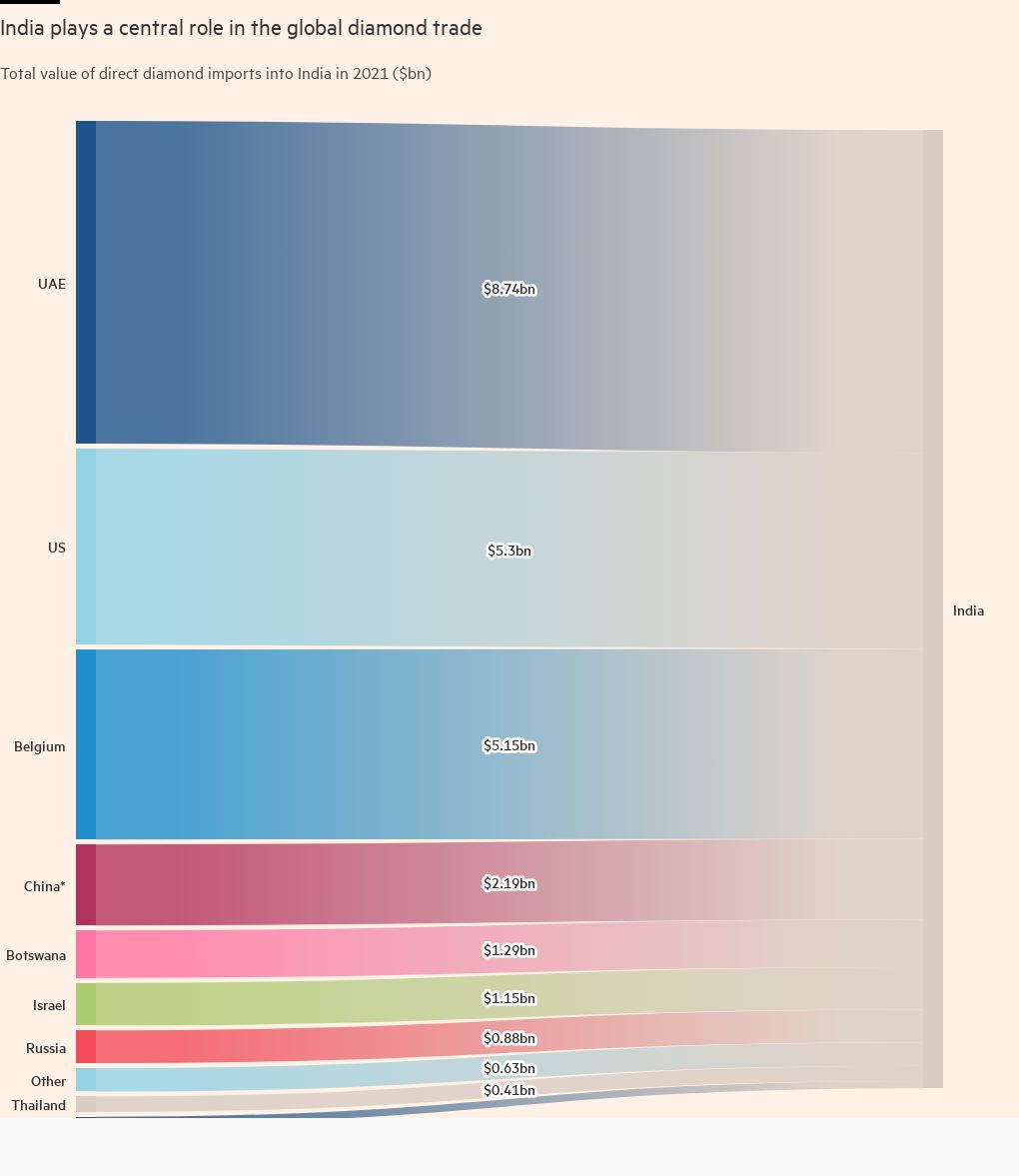

For India, which considers Russia a friendly nation and has not publicly rebuked Putin, removing Russian diamonds from circulation puts hundreds of thousands of jobs at risk — from the diamantaires (or diamond dealers) in Mumbai who sell to jewellers worldwide, to small traders like Savaliya and the roughly 25 polishers he employs.

“Russian diamonds are 60 per cent of the job creation in the [Indian] industry,” says Anoop Mehta, president of Mumbai’s vast Bharat Diamond Bourse, who estimates that India’s total diamond trade employs 1mn people. “They’re cheaper quality and smaller sizes . . . the smaller and cheaper the stone, the more people you need to cut and polish it”.

Savaliya has found himself in the eye of a geopolitical storm he wants nothing to do with. “From my point of view, two countries have a problem,” he says over a magnifying loupe on his desk in Surat, “and the whole world should not be bothered about it.”

The little brilliants glittering across a velvet tray on Savaliya’s desk were once hidden under snow-blasted Siberian tundra.

After being hacked out of Alrosa mines, the rough diamonds were then bartered by traders across the world, before finally ending up in Surat’s backstreet polishing industry.

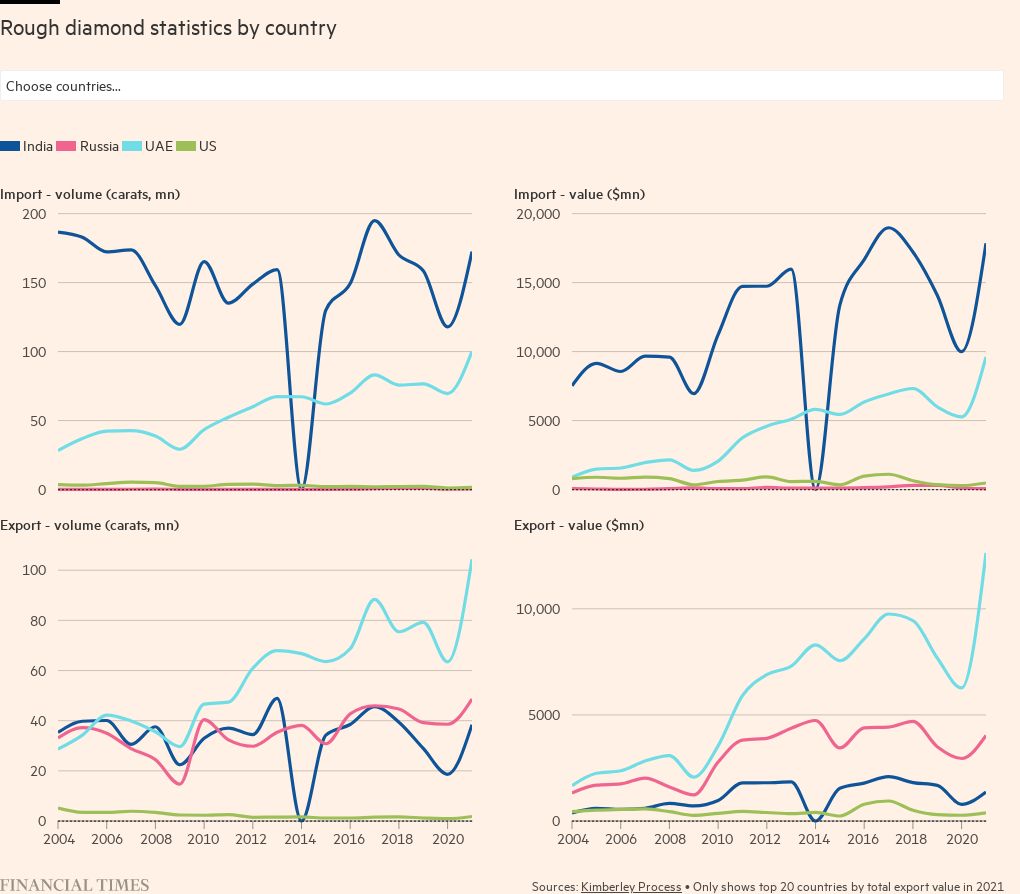

The opaque supply chain is far from the glamorous, exclusive image cultivated by diamond marketers. According to Edahn Golan, a diamond industry analyst, about 30 per cent of diamonds by volume come out of African mines operated by De Beers, which is owned by London-listed Anglo American, while 40 per cent come from Alrosa’s mines in Russia.

The miners sell to selected diamond dealers based in the hubs of Antwerp, Dubai, Mumbai and Tel Aviv, who have rights to a certain quantity of rough diamonds per year — coveted positions, given there are so few diamond miners to buy from directly.

But diamonds are an unpredictable commodity, and as buyers search for the size, clarity and colour they need, they filter out the ones they don’t and sell them on. The precious rocks “change hands many, many times”, says Russell Mehta, managing director of diamond dealer Rosy Blue India, at his plush office in Mumbai’s diamond bourse.

Mehta explains that diamantaires like Rosy Blue — which is qualified to buy rough diamonds direct from miners including Alrosa — spread the diamonds out across the supply chain by selling the jagged pieces they don’t want to traders in other hubs.

Those traders may have them polished in India, by contractors or their own workers, or hawk them to someone else. Eventually, polished diamonds flow back up to the diamantaires, who aggregate them to sell to buyers such as Tiffany, Signet Jewelers, Cartier or Harry Winston.

These packets of rough diamonds can only be sold if they are accompanied by a Kimberley Process certificate. As diamonds are sorted, selected and traded along this rough diamond supply chain, they get mixed in with stones from other mines — and become indistinguishable from each other. The KP certificate will show an aggregated package as “mixed origin”.

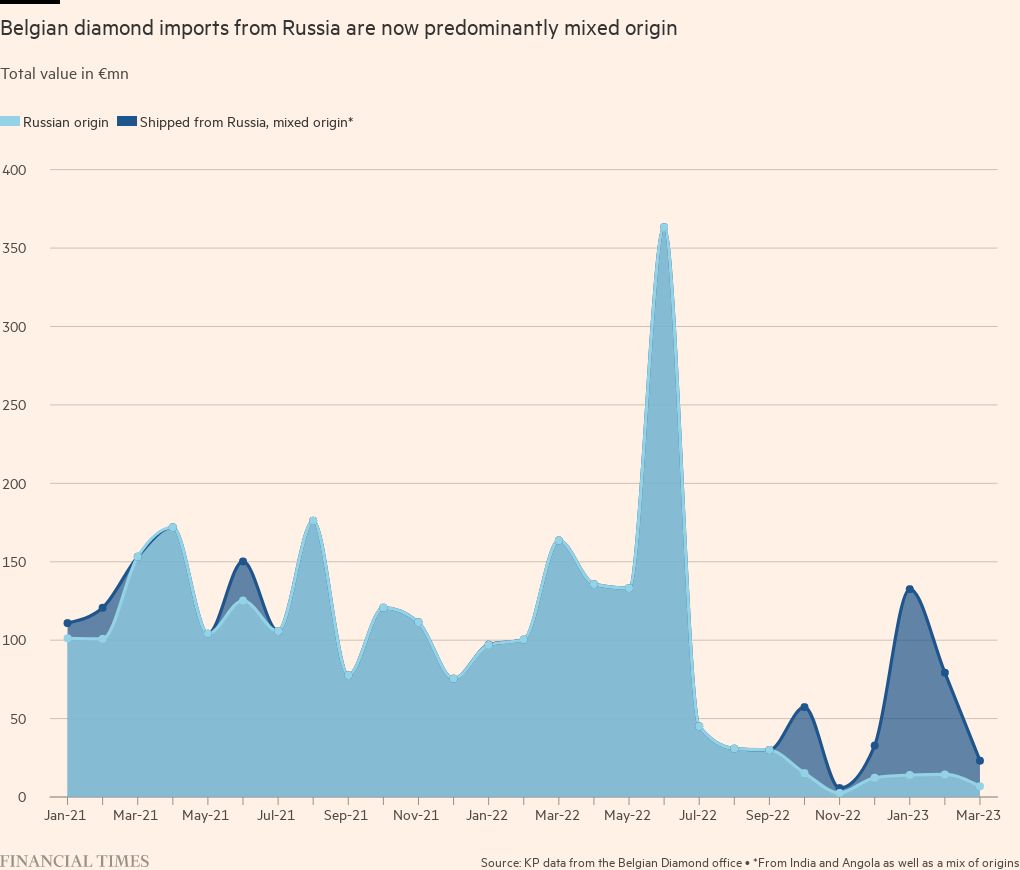

Russian diamond exports to Belgium reveal a huge surge in the parcels of diamonds classified as “mixed” origin in the past six months, from zero during April to September 2022 up to a value of €42mn in October and rising to €118mn by January 2023. The KP does not prohibit diamonds exported from Russia, which is one of its signatories.

Hans Merket, a researcher at the International Peace Information Service, an Antwerp-based think-tank, says the west has become frustrated with the KP’s rigidity on Russia.

“G7 countries are [currently] putting energies and resources into a process that certifies Russian diamonds as conflict free. They don’t want to leave this system as they need it, but they’re not happy with how it’s going,” says Merket.

In theory, a traceability scheme could change that. Today, only the biggest and most valuable diamonds are individually bagged and accounted for, says Rosy Blue’s Mehta. Some clients require suppliers to keep an audit trail, while De Beers also has a “Forevermark” certified chain that is priced higher. Mehta also has his own management systems to avoid fraud or theft for certified stones. All this tracking adds costs.

Below a certain size, however, tracing becomes prohibitive. “I can’t track and trace small diamonds. Period,” Mehta says. In India, the polishers he works with like Savaliya are “a cottage industry . . . And if [they] don’t have systems and processes to prove [non-Russian origin, they] simply cannot sell.”

Rosy Blue stopped buying from Alrosa after the war broke out, Mehta says. “I have customers who don’t really care about the Russian diamonds, like in India and in China . . . But then why create even some sort of a ghost or phantom in the minds of my other customers?”

In the past, all diamonds polished in India were classified as being Indian origin, as they are — in export parlance — “substantially transformed”, meaning they could still legally be imported to America. That could change, with the G7 traceability initiative paving the way for the US to close the transformation loophole. It might also convince Europe to join the sanctions regime.

The traders who scrutinise stones on the desks of Antwerp’s diamond bourse have, for the past few months, been under special protection.

In debates among EU members, Belgium has held out against adding diamonds to the bloc’s sanctions packages on Russia, diplomats and industry insiders say, because it is unwilling to risk Antwerp’s five-centuries-old status as a massive diamond trading hub.

But as Russia’s war has worn on, the European nation has had a change of heart. Alexander De Croo, the Belgian prime minister, tells the FT that his country intends to be a “leading partner” in the common endeavour to stem Russia’s financial flows from the diamond trade.

“We want to carve out Russian diamonds from western markets. But we won’t achieve this with the existing direct bans of Russian diamonds. They haven’t had any meaningful impact on the financial flows for Russia’s war machine,” he says.

A traceability scheme could prevent Russian diamonds from getting relabelled in third countries and ducking sanctions. “Real impact can only be achieved when we combine a direct and an indirect ban against Russian-mined diamonds,” says De Croo.

“In order to do this, we need a gradual introduction of traceability in the sector. This will require some time. But it shouldn’t stop us [from acting] now.”

The G7 and EU have been examining ways of creating an effective tracing system with global teeth, inspired by last year’s collective effort to impose a ceiling on Russian oil export revenues.

But how? Belgian industry players fear trade being diverted to other hubs such as Dubai, while failing to prevent Russian diamonds from being repackaged as originating in other markets and continuing to flood into the west.

“We will never accept any solution that is just based on rubber-stamping,” says Tom Neys, a spokesperson for the Antwerp World Diamond Centre.

So the idea, said one European official, is to come up with a system that “allows us to get a grip on the entire value chain, so we can do a direct and indirect ban, and so that the circumvention gate is closed from the start”.

That is easier said than done. Officials are concerned that paperwork can be doctored to disguise a diamond’s origins, and have therefore been examining technological solutions to better identify the stones’ provenance.

Ideas include machines that can analyse a diamond’s likely geographical origins by detecting and analysing its trace elements, or so-called nano-markers that can be engraved on a diamond and remain even after cutting and polishing.

But there’s a flaw in the tech plan for tracking and tracing diamonds — it’s not ready to roll out at mass scale. Pavlo Protopapa, chief executive of Spacecode, which has been developing technology to analyse the origins of diamonds, says prototypes of his machines won’t launch until the end of the year or early in 2024.

The upshot, says the European official, is that there will probably be a “transition period” towards a more robust system after EU diamond sanctions are introduced.

But not everyone in the industry believes the tech tracking solution is feasible, and worry that the G7 has yet to come up with a credible solution for policing its reimagined diamond supply chain. They say that strengthening an existing system of written supplier declarations would work better.

“It’s just a mess,” says one Mumbai dealer, who has been consulted by western officials working on the measures.

However it is introduced, a traceability scheme would bring upheaval for everyone in the fragmented and complex diamond supply chain.

Some complain it will push up costs in a commodity business where margins can be thin. One diamond industry executive fears that a cumbersome G7 initiative would risk affecting demand for natural gems across the board and hitting supplies from the informal sector the hardest.

“This creates a risk for us all,” the executive says.

Paul Zimnisky, an independent diamond market analyst based in New York, says that he sees flows splintering. Some will end up trading with Russia and China, while other verifiable supply sources head west, he predicts — even requiring processors and dealers to keep separate facilities for Russian and non-Russian diamonds.

“If they have major clients saying ‘we don’t want you to deal in Russian goods’, then they need to make a decision and will have to separate their supply chains and factories,” Zimnisky says.

The success of the G7 scheme hinges not only on Europe and the US, but on co-operation from other countries — not just the Southern African nations where many rough diamonds originate, but also India, the chokepoint for huge volumes of the world’s gemstones.

One of the big uncertainties hanging over negotiations is how New Delhi will respond. India’s Ministry of External Affairs declined to comment on the country’s position and referred the FT to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, which did not have an immediate response. India’s government-backed Gem and Jewellery Export Promotion Council did not respond to a request for comment.

But for the country’s diamond industry, what American consumers demand is just as important. There is “no option”, sighs Dinesh Navadiya, chair of the Indian Diamond Institute. “When you talk to Big Daddy you just say yes,” adds the Mumbai bourse’s Anoop Mehta. “You don’t argue.”

New York-listed Signet Jewelers, which calls itself the world’s largest diamond jewellery retailer, already started to expunge Russian metals and diamonds from its supply chain last year.

Tiffany has directed its suppliers to stop buying Russian rough diamonds for them, and to segregate Russian and non-Russian “melee” — the tiny diamonds used for embellishments, one of Surat’s specialities.

For its part, the Indian diamond industry has lobbied for the G7 to start its track-and-trace programme on bigger diamonds — one carat or above, which are already certified — before moving down to the smaller stones that its small manufacturers depend on.

In Surat, manufacturers say there is already a slowdown. Savaliya complains the supply of rough diamonds has become worse since the war in Ukraine started, with rough prices rising while polished prices stay down, eroding his 4 per cent profit margin to nil.

He has operated his one-room factory at a loss for the past six months, and for the first time in his nine years of running the workshop Savaliya has decided to close for a holiday — and he is not sure when he will reopen.

However, he grudgingly accepts he could find ways to adapt to a G7-directed diamond supply chain. “It is possible to keep [Russian gems] separate,” Savaliya assents, before adding with frustration: “But the expenses are bound to increase.”

Additional reporting by Anastasia Stognei in Riga

Photographs by Karen Dias for the FT

Data visualisation by Dan Clark and Sam Joiner

Comments