African countries ‘ready to open our doors again to the world’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Cape Town’s international convention centre, converted into Africa’s biggest field hospital during the pandemic, has started booking events, albeit socially distanced ones. Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, plans to reopen some schools on Monday. And in Ghana, where Accra’s international airport has been open since the start of the month, bars, restaurants and places of worship are slowly getting back to normal.

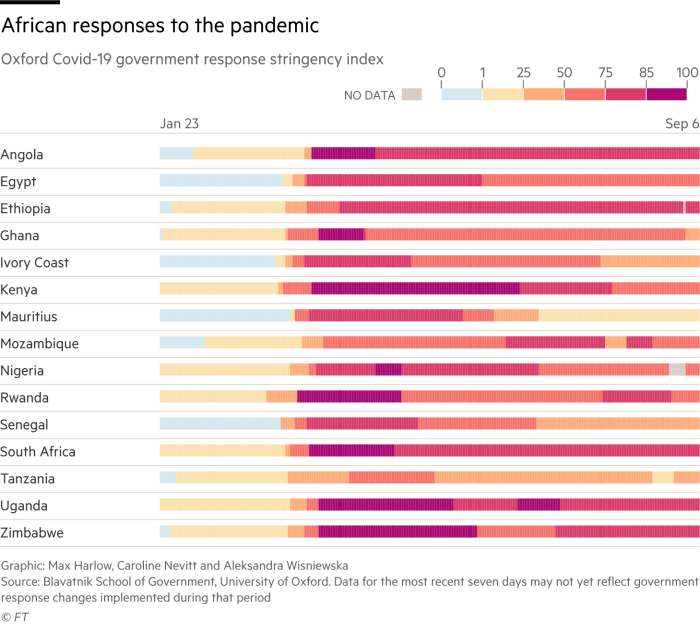

All over Africa, encouraged by low or declining death and infection rates, countries are tentatively opening up in the hope of reviving pandemic-scarred economies. With significant variation from country to country, schools are reopening, curfews and travel restrictions are lifting, and markets are getting back to full capacity.

Authorities are being pushed to reopen by the severe impact of lockdowns on livelihoods, particularly for informal workers who need to venture out each day to make a living. But they are also encouraged by growing evidence that Covid-19 has not been as deadly in much of Africa as originally feared.

The continent, which has 17 per cent of the world’s population, has recorded 33,430 deaths from Covid-19, or about 3.5 per cent of the global total. Even if that underestimates the true number, John Nkengasong, director of Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, said that Africa appeared to be “slowly bending the curve” of new infections.

In South Africa, which has recorded more than 650,000 Covid-19 cases, nearly half of those on the entire continent, infection rates have fallen to below 2,000 a day against a peak of 12,000 two months ago. Deaths, officially at 15,722, have also slowed to fewer than 100 a day.

After a strict lockdown, which triggered a 16 per cent economic contraction in the three months to June, South Africa will reopen its borders from October, six months after it first halted international traffic. In a televised broadcast, President Cyril Ramaphosa said: “We are ready to open our doors again to the world.”

Severe restrictions on the sale of alcohol are being eased and visits to game parks encouraged. “We asked you to stay, now come out and play,” went a tagline from South Africa’s tourist board, which nevertheless urged people to wear masks.

Travellers to South Africa will have to test negative for Covid-19 less than 72 hours before departure, a requirement similar to other countries such as Kenya. Despite South Africa’s tentative reopening, the economic impact is expected to remain severe, with some economists predicting the jobless rate could leap to 50 per cent from 30 per cent before the pandemic.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has also been badly hit economically, largely because of a fall in oil prices that make up 90 per cent of its export revenues. Economists are predicting the worst recession in decades.

Yet the health impact there has been less severe. Of its 200m people, 1,100 have died from Covid-19 out of 48,000 infections. In Lagos, temperature checks and mask-wearing are enforced at stores and restaurants, markets are bustling and yellow public transport minibuses are packed.

Babajide Sanwo-Olu, Lagos’s governor, warned in a recent tweet: “The gradual easing doesn’t mean the pandemic is over. It is not an invitation to carelessness or nonchalance.”

In Kenya, where infection rates have also been falling, the government is considering accelerating school openings — planned originally for January — to as early as next month.

“I want to go back to school, I love school,” said Larin Otieno, a 13-year-old student in Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum. “I will take all the precautions. I will wear a mask, wash my hands, use hand sanitiser.”

Jared Omusula, the headmaster of a private school with rickety galvanised walls, also in Kibera, was against reopening. “It’s not safe to open in October,” he said. With an estimated 1.7m Kenyans losing their job between April and June, Mr Omusula said, many parents had in any case returned to their villages, taking their children with them.

Most air and land links have been restored to Kenya, but the battered hospitality industry is waiting for an easing of a dusk-to-dawn curfew, in force since March alongside a ban on alcohol sales.

“The shock is there, but the recovery will arrive sooner than expected,” said Kwame Owino of the Institute of Economic Affairs in Nairobi, who echoed the country's central bank forecast that estimated Kenya’s economy would grow 2.5 per cent this year, against 5.4 per cent in 2019.

Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, said that apart from South Africa and the big oil producers such as Nigeria, Angola and Gabon, other economies would bounce back faster than expected. “Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are going to outperform the global economy,” he said, adding that Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and several others would grow this year.

Contrary to the World Bank’s prediction that remittances would fall as migrant workers lost jobs in rich countries, Mr Robertson said, they had risen as relatives sent back more money to cushion the economic shock. Remittances to Kenya were up by a fifth, he said.

Victoria Cooke, director of Gallery 1957, an art business in Accra, returned to Ghana last week to find things better organised and busier than in the UK, where she had spent lockdown. Three high-end restaurants had opened in Accra during her absence and the Kempinski Hotel, though strict on masks and sanitiser, was busy with official delegations, she said.

Ms Cooke had also been impressed by Accra airport, where an on-arrival Covid-19 test was processed in 20 minutes. “It was impressive, slick and quick,” she said.

Still, as more countries moved towards reopening, Mr Ramaphosa of South Africa struck a note of caution. “We cannot afford a resurgence of infections,” he warned. “A second wave would be devastating.”

Additional reporting by Neil Munshi in Lagos and Donald Magomere in Nairobi

Comments