Myanmar artists highlight history and struggle in Singapore Art Week

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Yeo Workshop opens its booth at the Art SG fair in Singapore next week, a painting by Burmese artist and poet Maung Day will hang there, depicting a bucolic backdrop in a delicate style that is at once surrealist, whimsical and naive. But just before the rolling hills and verdant woods is a disquieting element: a dog standing next to a corpse.

Called “Dog Found the Murdered Body of His Master on the Beach”, the acrylic painting illustrates a real-life murder that shook the fishing community in Rakhine state in Myanmar, where Maung Day used to live. The murder was part of the post-coup turmoil of recent years: on February 1 2021, the military seized power, putting an end to the democratic transition started by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party. Since then, more than 2,600 people have been killed and 13,000 arrested, according to a domestic human rights organisation.

Like many other murder cases in Myanmar, the culprit behind the murder in Maung Day’s picture has not been found. “The political instability and ensuing acts of violence have been an everyday reality throughout the country over the past two years,” the artist has said.

Part of a presentation by curator Louis Ho for the Singaporean gallery Yeo Workshop, the artwork highlights the tensions and violence in that region of Myanmar. Singapore Art Week, which includes Art SG, is “a timely platform to reflect on the plight of the Burmese people, especially those poor, rural, minority communities, who are most vulnerable to the violence”, says Ho. And his presentation is not the only one to highlight Burmese artists.

Since elections in Myanmar in 2010 and the 2012 by-election victory of the National League for Democracy party, Burmese art had been on the rise. Private galleries, such as Art Seasons and Yavuz in Singapore and Thavibu gallery in Bangkok, and public museums, notably the National Gallery Singapore, have started exhibiting the work of Burmese artists. A 2013 exhibition organised by the Guggenheim and a 2017 show in Tokyo included many works by Burmese artists and in 2021 the Centre Pompidou in Paris dedicated a large-scale exhibition to the Burmese modernist Bagyi Aung Soe.

But the coup’s leaders brought growing domestic artistic freedom to a halt, blacklisting anti-coup artists or those who had made pro-democracy work or art dealing with sexuality. This violence added to the oppression of local ethnic and religious groups, including the Rohingya people, the Muslim minority now confined to Rakhine state and victims of a genocide by the military rulers.

Artists within the country never stopped working, but they are under strict censorship and the constant threat of incarceration. Art fairs and art weeks are a good chance to see their works since they have limited possibilities to show within Myanmar or are in exile abroad.

Htein Lin, a prominent painter, performer and activist who has been involved in resistance movements for decades, became a cautionary tale. He was thrown in prison last August, along with his wife Vicky Bowman, the former British ambassador, charged with breaching immigration laws. They were finally released in November in an amnesty of political prisoners.

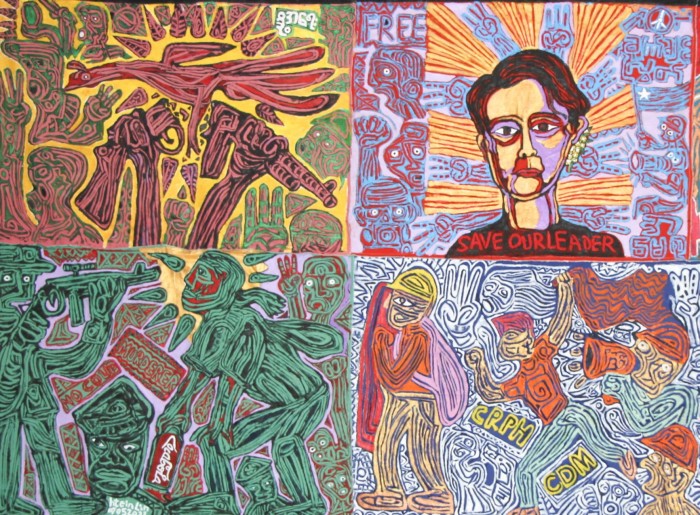

“It seems as if news of Htein Lin’s arrest was what jolted the art community in Singapore and south-east Asia [into greater awareness],” says Ho, who also curated Htein Lin’s solo show Another Spring at Richard Koh Fine Art in Singapore in 2022. At Art SG, Koh’s gallery is showcasing pieces by two Myanmar artists, Aung Ko’s “The Burmese Tiger and English Hunter” and Wah Nu’s cloud paintings.

For most artists who decided to leave the country after the 2021 coup, the challenge is to highlight the condition in Myanmar and still be subtle enough not to endanger their families back home. That’s why most of the works that will be showcased in shows and on fair booths prefer to address specific issues using symbols and ancient tales.

Examples of this are the pieces at the SEA Focus fair presented by Intersections, a gallery which focuses on contemporary art from Myanmar, Singapore and France founded by Marie-Pierre Mol. She will show “Lost Children 1”, a work by Maung Day revisiting the story of how the pied piper led children to disappear — a pervasive plague in Myanmar — and “Tales (The Kiss)” by Kyaw Htoo Bala, a young Yangon-based artist who studied at the Lasalle College of the Arts. “Bala recently opened an art space in Yangon,” says Mol. “I think it’s just amazing that he managed to do this at this time. It shows the resilience of Burmese people.”

Bala’s almost monochromatic collage is made with a traditional paper produced only in Shan state and was inspired by the stories his grandfather told him when he was a young boy. As an adult, the artist realised these drew on the history of his family, his neighbourhood and his country. “At the moment,” says Bala, “I’m creating my own stories based on the events in my life. For instance, a piece I will show in Singapore called ‘The Kiss’ . . . was inspired by lovers who seemed unaffected by the confusing, nasty and oppressive turmoil around them.”

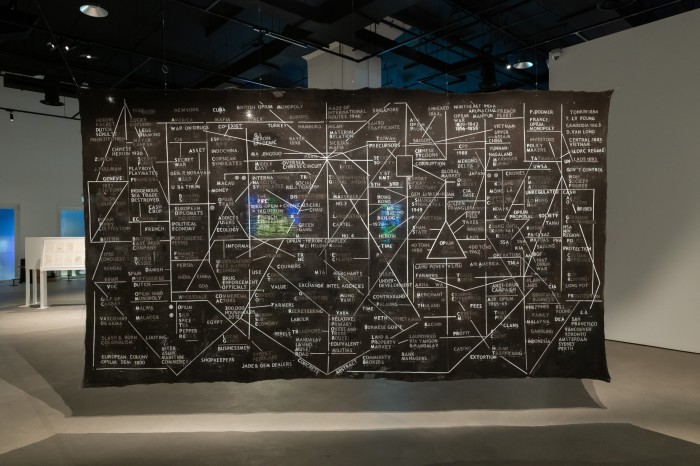

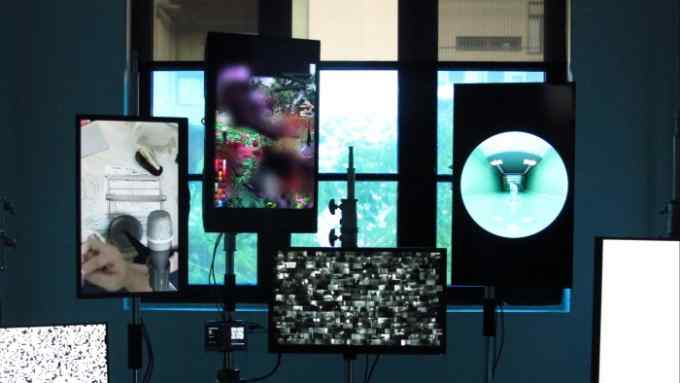

Outside the fair, there are works that indirectly address the deeper roots of the crisis. This is the case with Burmese artist Sawangwongse Yawnghwe, who presented two pieces at the Singapore Biennale in 2022, “The Opium Parallax” and “Footnotes”. These installations explore the history and conditions surrounding the opium trade in and around Myanmar. The first consists of a suspended panel: one side presents a simplified version of the history of the opium trade, the other shows a map of the complex web of relations between drug-dealing and geopolitics.

Yawnghwe is a descendant of the Shan royal family, and his grandfather was the first president of the Union of Burma, the party which ruled the country from 1948 to 1962 after independence from Britain. Following his death in prison after the 1962 military coup, Yawnghwe’s family formed the resistance of the Shan State Army, before being forced into exile.

Yawnghwe’s artistic practice can’t help but delve into the national history: “In my work there is always the desire of going back to the roots. But as a Burmese artist my roots have been completely destroyed,” he says. “Instead of being annihilated by this realisation, I look at this as a unique chance for freedom — a way of getting into new territory of how I define myself and my work as an artist.”

Comments