Interview: Philippe Léopold-Metzger and Chabi Nouri, Piaget’s old and new CEOs

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Johann Rupert, chairman of luxury conglomerate Richemont, decided the company needed a chief transformation officer in November 2016, few imagined the scale of the changes he had in mind. In January alone, Richemont announced four new chief executives of brands, and two further brands lost their chief executives to more senior roles within the group.

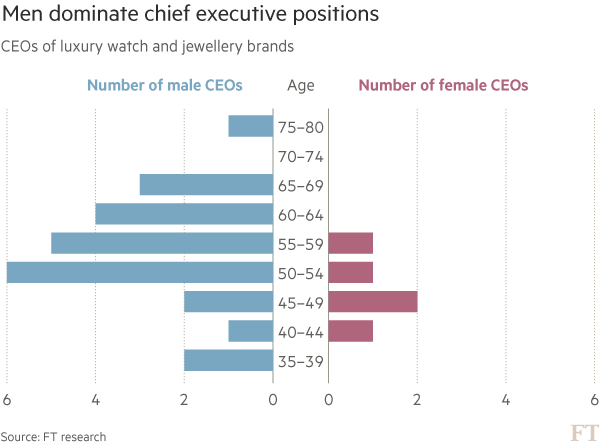

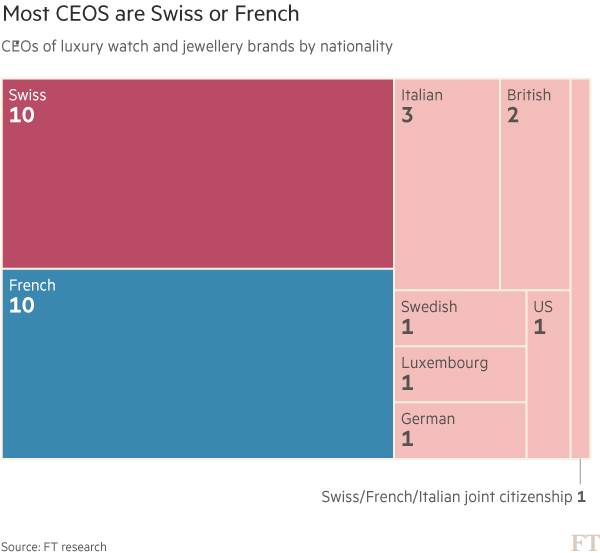

Another transformation Mr Rupert felt necessary was in Richemont’s male, francophone management. He told investors at the end of 2016 that he wanted to see “less grey men, less grey Frenchmen as a subcategory. We have too few women. We don’t have enough diversity.” (See industry data below.) Richemont’s all-white board has 19 members but only one woman, and there are no female chief executives at its watch and jewellery brands. That changes, however, next week.

On April 1, Chabi Nouri will be promoted to chief executive of Piaget from international managing director for sales and marketing, succeeding Philippe Léopold-Metzger, who has been in the job since 1999.

Ms Nouri is not the first female chief executive at Richemont. However, based in Plan-les-Ouates, a Geneva suburb where many watch brands have headquarters, she is the first at the heart of the horological industry. She plays down the gender issue and says that during her years at Cartier, also a Richemont brand, “being a woman was never a disadvantage”.

Her appointment signals a change in direction for the house. Piaget was founded as a watchmaker in 1874 and until the mid-20th century it supplied other brands with movements, after which it started selling watches under its own name.

During the 1960s and 1970s the brand gained a reputation for jewellery-watches, but its emphasis has tended to be on the watch element.

The watch industry has suffered since 2014 — Swiss exports were down 10 per cent globally in 2016 alone — but the jewellery market remains relatively buoyant, having grown 7.5 per cent in its 10 biggest markets in 2016, according to Euromonitor. Ms Nouri’s mandate is to boost Piaget’s presence there.

For the past two and half years Ms Nouri has worked with Mr Léopold-Metzger. He now acknowledges that, during his stewardship, Piaget concentrated on being taken seriously as a watchmaker at the expense of its jewellery. But given the changes in the market, “with hindsight, what I do regret is I could have started the strong development of jewellery earlier”.

In contrast to Ms Nouri’s demurral on gender, Mr Léopold-Metzger feels that a woman will have a greater affinity with jewellery: “Jewellery is very driven by beauty and elegance, and is more feminine than masculine. It is not the key advantage but I think definitely more an advantage than a disadvantage to have a woman leading the company.”

He is not, of course, suggesting that Ms Nouri rose to run a Richemont company because of “beauty and elegance”. Between her departure from Cartier in 2008 and her arrival at Piaget in 2014, she worked at British American Tobacco as global head of brand for Vogue cigarettes and was about to move to Japan with BAT when she was contacted by her old boss at Cartier, Bernard Fornas, who had been promoted to run Richemont. Mr Léopold-Metzger also received a call from Mr Fornas, encouraging him to meet Ms Nouri, though he denies he was under instructions to appoint her as director of marketing, communications and heritage.

Ms Nouri says she would not have joined if she had thought she was being foisted on others. “It was Philippe who had to want me to be here for this transition. If not, I would have not joined to fight.” They met, to test out their chemistry, and “most of the elements were quite in agreement”.

But while their personalities worked together, their experiences in the watch and jewellery industries could hardly have been more different. Mr Léopold-Metzger belongs to an earlier generation of management where intuition, not experience or rigorous analysis, played a more important role than it does today, he says.

He joined Cartier in 1981 and helped to built the brand into a dominant force in today’s global luxury market. (Cartier was responsible for most of Richemont’s €6.1bn jewellery sales in 2016.) He ran Cartier in Canada, the UK and Asia before taking over Piaget.

***

These days Richemont is a global business, and there is less place for intuition, as Mr Léopold-Metzger concedes: “Every time I see a product I’m excited, I want to launch it, and probably we have too many launches, which could have been launched later and been more focused. The times changed, and today we are in a much more marketing-driven world than five or 10 years ago.” As he says of Ms Nouri, “I think she’s a better marketeer than I was.”

Ms Nouri confirms that, under her management, there will be fewer launches; her priority is to “raise the awareness of these icons and make sure that they are known”. Given that her boss as of April 1 will be Georges Kern, Richemont’s new head of watchmaking, who built the IWC watch brand on such a policy, she is certainly on-message.

If Mr Léopold-Metzger describes his successor as a better marketeer, what is it that Ms Nouri admires about the man she is replacing? She thinks and answers carefully. “Philippe is probably the most ethical [man] and the man with the most values I’ve met. He really stands by his values and his ethics, and that’s quite amazing, I have to say.” He laughs: “You can translate that as ‘old guy only focused on the past’.”

He does not say this bitterly, but with a hint of nostalgia, and he wishes that he were leaving the role of chief executive at a better time for the company. “I would have preferred to end up with the growth continuing, but . . . it is the beginning of a new cycle.”

Besides, he is not leaving the business completely, as in April he will become non-executive president, overseeing special projects. “Some people probably would be happy if a brand collapses after their departure. But the best reward for me is to see the brand entering the next stage of growth,” he says optimistically. “Hopefully I’ll stay around a little bit so I can share some of the glory.”

Comments