The downturn in the dollar is not just about rates

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is the former chief investment strategist at Bridgewater Associates

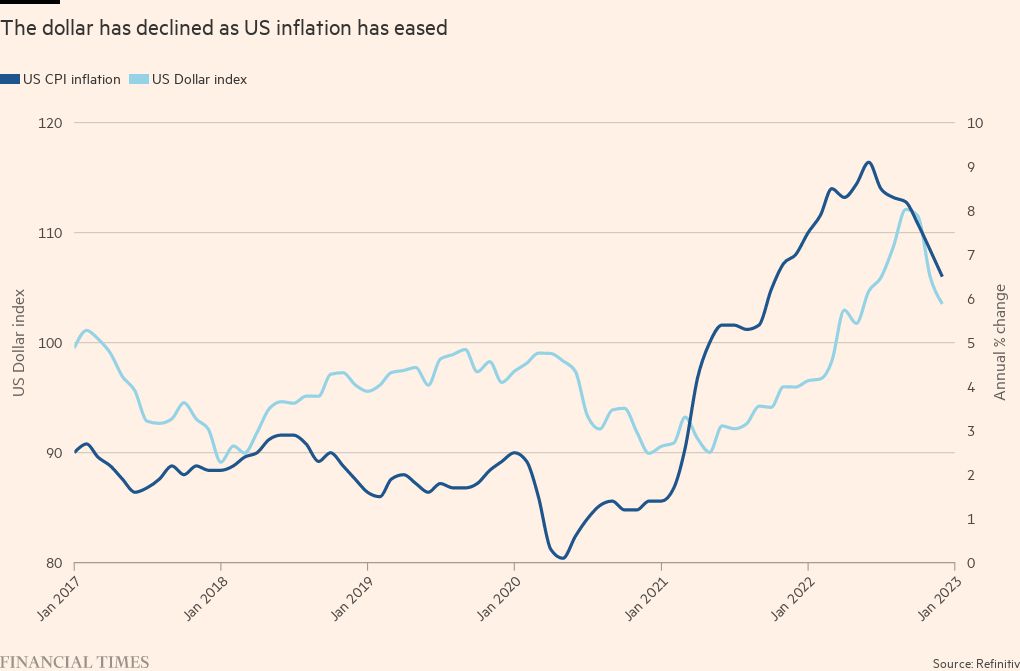

After steadily marching to a secular peak against a basket of its key trading partners last fall, the US currency has been quickly declining.

Moderating expectations for US interest rates explain much of this about-face, but not all. Indeed, to understand the most recent dollar weakness — and more importantly, where it is likely to be headed next — events outside the US will matter as much or more than what happens within its borders.

It all comes back to the dollar’s unique standing in global currency markets, which allows it to appreciate in two opposing environments. In part because of its global reserve currency status, it does well when the world is not doing well. In that scenario, investors want the relative liquidity and safety of US assets, especially Treasury bonds. This even tends to be the case when such shocks are home grown, as was the case after the US debt ceiling crisis in 2011.

At the same time, though, the dollar also strengthens when US economic growth is robust — and specifically more so than its peers. This often goes hand in hand with expectations for relatively more attractive US yields and equity returns that increase dollar demand.

Where the currency tends to underperform is when the country is doing OK, but no better (or relatively worse) than peers. That environment often means US interest-rate differentials are less likely to be the dominant factor pulling capital towards America. In such circumstances, US investors often have greater confidence to take more risk on overseas assets, especially if prospects for those markets are improving. That is exactly what has happened so far in 2023 — the dollar has quickly lost ground against most of its developed and emerging-market counterparts.

So where from here? To see the dollar continue to depreciate, it’s not enough that it is expensive relative to history and the US has a current-account deficit that requires funding. Most likely, we will also need to see the rest of the world continue to post economic data and implement policies that will shift capital to those markets. That’s possible but far from certain.

Beijing, for instance, is clearly doubling-down on supporting growth as it grapples with the societal cost of a quick exit from its zero-Covid policies, most recently deprioritising technology-related regulation and property deleveraging.

Stronger consumer spending, supported by potential improvement in sentiment towards the property market, would benefit expectations not just towards beaten-down assets in China. They would also benefit areas around the world that are sensitive to Chinese growth trends, from key commodities to favourite Chinese travel destinations. It is no doubt one reason that the Thai baht is the best-performing Asian currency so far in 2023, in part given expectations for a flood of Chinese tourists ready to spend.

Meanwhile in Europe, benign weather patterns have helped underpin stronger-than-feared economic outcomes in much of the region, reflected in measures of economic data versus expectations.

The dollar is likely to decline further if we continue to see a combination of improving economic conditions in the rest of the world, and a scenario of “immaculate US disinflation” that would allow the Federal Reserve to slow its pace of rate rises without unduly undermining growth. This would encourage investors to look to capture more attractive valuations and greater diversification through increased exposure to non-US assets.

Beyond suggesting continued US equity underperformance in relative terms, such a trend would take some pressure off overseas’ central banks that have had to intervene and raise interest rates in an attempt to slow sell-offs in their local currencies over the last several quarters.

But a word of caution. As is increasingly obvious after last year’s miserable misses by both many market participants and central banks, this is a time for humility — the potential for surprises remains high, be it in China’s reopening, the war in Ukraine or even winter weather affecting energy prices.

Moreover, it’s the same global optimism that is taking the dollar down from its recent peak that could sow the seeds for the next flight to safety. A rapidly, notably falling dollar would provide an unwelcome measure of support for US inflation — making the Fed more inclined to keep policy tight, even if it means a deeper recession. We are in a world with an ample number of catalysts that could reignite global growth and stability fears or lead the US to outperform again. For now, the dollar is down but not necessarily out.

Comments