Companies trying to exit Russia have to ‘dance with the devil’

Simply sign up to the War in Ukraine myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

After weeks of silence over the future of its Russian operations, Société Générale delivered a bleak blueprint for other multinationals that have pledged to exit the country.

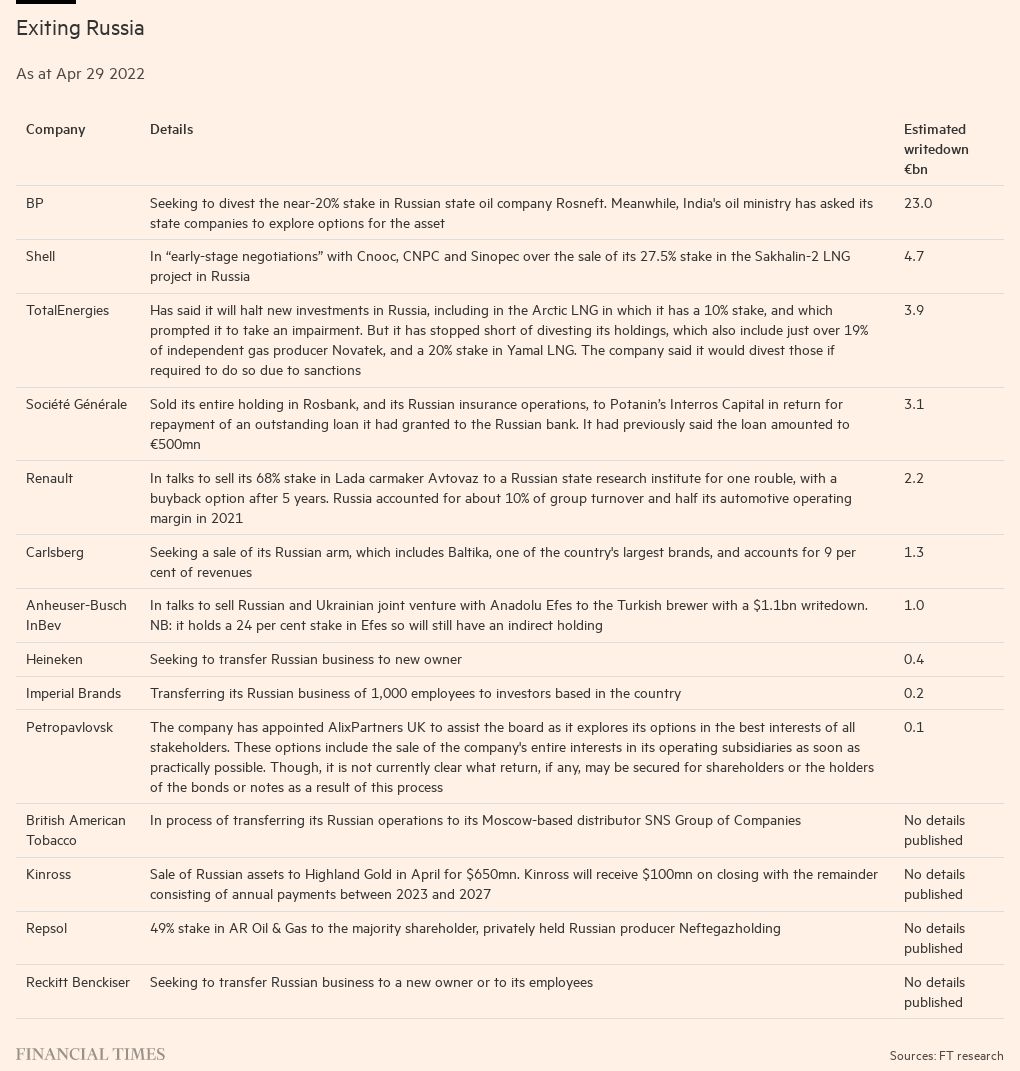

The French bank said in early April that it would sell its Rosbank network to Vladimir Potanin, one of Russia’s richest men and a nickel baron who has avoided EU or US sanctions, taking a €3.1bn hit in the process.

The transaction stunned some rivals and underlines the difficulties facing groups from oil majors to car companies who want to exit Russia following the invasion of Ukraine: few potential buyers, costly exit options and uncertain prospects for any future return.

“We are all trying to find a clever way to exit the country. But what SocGen did isn’t the best way to do it,” said one senior executive at a bank with operations in the country. “There is an ethical discussion . . . there is a reputational risk to consider when selling, or basically donating, to an oligarch.”

“Essentially they are giving a . . . gift to Potanin. OK he is not sanctioned, [but] is it the right thing to do?” the banker added.

Many western companies have found themselves caught between the prospect of expropriation by Russia, selling to locals caught in sanctions, or trying to scout out investment from Chinese or Middle Eastern buyers that might be freer to make deals but have so far shown little appetite.

SocGen is one of the few western groups to successfully agree to sell its Russian businesses. Rosbank, in which it first took a minority stake in 2006, had long been the source of internal tensions amid critical questions from investors. Despite the fact it finally became profitable in 2016, investment bankers praised the sale — which the bank negotiated on its own — as a clean and efficient way to get out.

“It’s impossible to continue in Russia, and there’s hardly anyone you can sell to. Everyone else is under sanctions; you can’t really sell to a Chinese buyer if they’re being asked to remain neutral. [SocGen] did really well,” said a person close to another industrial company trying to exit.

Corporate advisers are closely studying successful exits as hope fades for a rapid resolution to the war. “A lot of people assumed they’d just have to say the right thing, keep the lights on and they’ll be back in by Christmas,” said one consultant, but “the horizons are moving”.

The costs of a fire sale could be considerable, as Renault showed this week after it emerged that it was in talks to sell its majority stake in Lada-maker Avtovaz to the state for one rouble.

Under a deal outlined by Denis Manturov, Russia’s trade minister — which the French carmaker would not confirm — Renault would have the option of buying the stake back in five or six years at a price that takes into account any subsequent investments.

The divestment means Renault is giving up more than 14 years of investments, during which time it bought a 68 per cent stake in Avtovaz, overseeing a workforce of 40,000 and generating 10 per cent of its turnover and half its automotive operating margin last year. It has warned of a write-off of up to €2.2bn.

A New York executive with employees in Russia rejected the Renault model. “We won’t negotiate with the Russian government,” he said. But the limited options mean some are having to rethink.

A restructuring expert advising several companies on sales said: “A number of people made very grandiose statements about ‘we’ll never do this and we’ll never do that’ and now they’re thinking ‘oh bugger’. The reality is for most of these exits you’re going to have to dance with the devil at some point.”

For those exiting, the cost and complexities are high. Tobacco maker Imperial Brands said last week it was transferring its Russian business to investors based in the country, and estimated a non-cash write off of around £225mn. British American Tobacco would soon complete the transfer of its operations to SNS in Moscow, said the Russian company. Neither group would say if any money changed hands.

Last month, Canada’s Kinross Gold struck a deal to offload its Russian assets to Highland Gold, a company controlled by mining magnate Vladislav Sviblov, for $680mn in staggered cash payments. He took control of Highland in 2020 after buying a 40 per cent stake from sanctioned oligarch Roman Abramovich and other investors. Before the war, analysts had valued the Kinross Russian mines at as much as $1.6bn.

That deal highlighted the challenges of extracting sale funds given western restrictions on transactions with Russian banks. Kinross said its proceeds would be paid out between the end of 2023 and the end of 2027, backed by “an extensive security package that includes share pledges, financial guarantees and an escrow account”.

When Otis Worldwide, the lift maker, said this week that its growing concerns about the sustainability of its operations in Russia had pushed it to consider finding a new owner, one analyst asked: “Are you going to be able to get your bat back? Or are [the Russian authorities] basically going to squeeze you, so it ends up being a loss?”

Some companies are seeking ways to circumvent deals with sanctioned companies. French shipping group CMA CGM recently bought logistics group Gefco from Russian Railways by structuring the transaction in two stages. Gefco bought back its shares first, allowing CMA CGM not to have to hand the funds directly to the Russia group, two people close to the deal said. Neither group responded to requests for comment.

Others to have succeeded in selling to local management teams include Schneider Electric, Publicis and Inchcape, which has divested its transport and sales operations for BMW, Toyota and Jaguar Land Rover in Russia for £63mn.

Duncan Tait, Inchcape’s chief executive, said: “The general view [from shareholders] was you’ll get nothing from the business, and there was a concern that it will actually cost money if you keep the business and run it down.”

Many businesses are concerned about dealing with any official Russian counterparty, or other individuals or groups that may yet be sanctioned. “It’s like the walls are closing in . . . What comes first? I get the deal away or my buyer gets sanctioned?” said one adviser.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that many western executives have recused themselves from any discussions around sales that could expose them personally to sanctions violations.

The alternative option for divestment is to find international bidders. But the restructuring expert said there had been fewer than they expected. “Everyone would like this to be solved by the Chinese, the Indians and the Turks because it’s clean and it’s easy, but the greater reality is, [the buyers] are Russians.”

Shell is in “early stage negotiations” with Cnooc, CNPC and Sinopec over the sale of its 27.5 per cent stake in the Sakhalin-2 liquefied natural gas project, but one industry veteran called it “a nightmare negotiation” because any Chinese deal would probably come at a big discount and require bilateral political agreement between Russia and China.

One Turkish energy adviser suggested Italy’s Saipem could transfer its shares in a company helping to build Arctic LNG 2, a natural gas development project, to its Turkish partner Ronesans. The Belgian brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev is in talks about selling its stake in its Russian and Ukrainian joint venture with Anadolu Efes to the Turkish beer maker.

But Turkish businesses are cautious for now, expressing concerns over complications with financing for acquisitions, which mostly comes from western banks.

The final option for multinational companies is to stay put. One adviser cautioned on the complexities of continuing to operate in Russia. “Procurement may be done outside Russia, financial transactions, and licensing of brands, intellectual property assets — how do you handle that?” he said.

Many foreign companies have so far held back from any public announcement of withdrawal — if only while they seek the least painful option. Prof Jeffrey Sonnenfeld at Yale School of Management calculates that more than 750 companies have curtailed operations in Russia but categorises 216 as “digging in” by refusing an exit.*

TotalEnergies, which holds a 19.4 per cent interest in gas producer Novatek PJSC and stakes in large LNG projects, has said it is ceasing new investments as the start of a withdrawal, though it has stopped short of trying to sell its stake in projects unless sanctions are ratcheted up.

It is the only oil major to have openly expressed doubts about quitting Russia, or at least selling to oligarchs. “We never stated we will stay in Russia”, said CEO Patrick Pouyanné. “We have just not stated that we will exit from Russia, which is a little different,” after previously stressing that walking out would hand back valuable resources “for free to Mr Putin”.

Additional reporting by Nikou Asgari, Peter Campbell, Judith Evans, Ian Johnston, Neil Hume, Laura Pitel and Tom Wilson

*This article has been amended to correct the estimated numbers of companies curtailing operations or refusing an exit.

Comments