Galleries and auction houses at loggerheads in Seoul

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

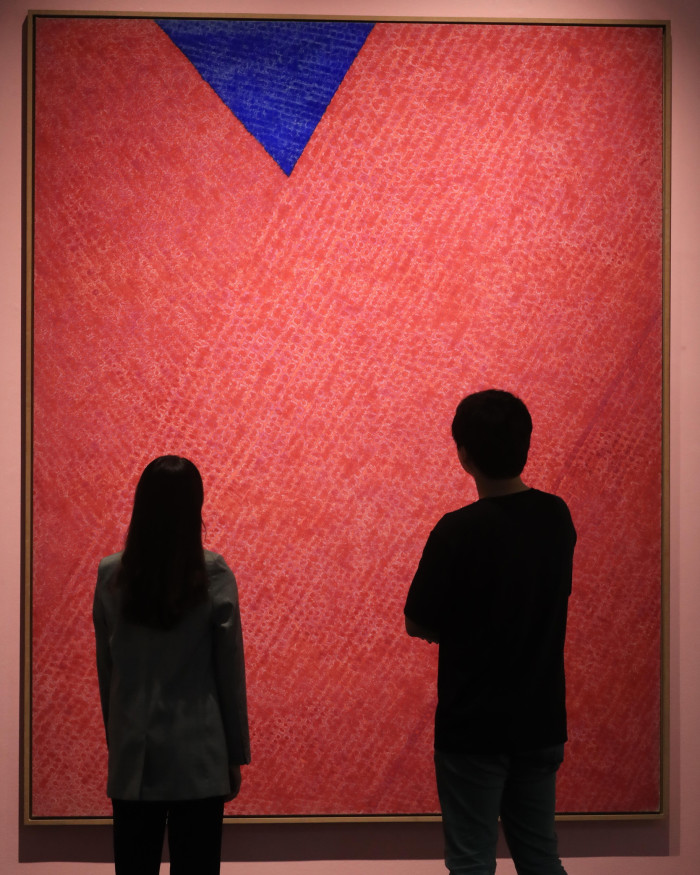

The inaugural Seoul edition of the Frieze Art Fair marks a defining moment in the history of the South Korean art market.

A pandemic-era boom, the growing presence of big-name international galleries, and the Hong Kong market’s travails amid concerns over censorship and Covid restrictions have all contributed to a sense that Seoul is ready to emerge as the region’s leading art industry hub.

But amid the self-congratulation there are also tensions. Local galleries are angry at the number of auctions being held by the leading auction houses — particularly of new works by young emerging artists most coveted by a new generation of collectors. Galleries also complain that the auction houses have been contacting artists directly and holding public viewings of their work in one-off shows in popular venues such as fashionable department stores.

“Excessive and frequent price fluctuations caused by auction houses are causing damage to artists who should be recognised for their artistic value instead of being subject to extreme capitalist logic,” runs a strongly worded statement issued in January this year by the Galleries Association of Korea. It accuses leading auction houses Seoul Auction and K Auction of violating a 2007 “gentleman’s agreement” designed to assure “healthy coexistence” between galleries and auction houses.

“Now is an important time to expand the base of the Korean art market and to step forward into the global art market. But this requires clear regulations on the roles and functions of domestic galleries,” runs the statement, issued in the name of Galleries Association chair Hwang Dal-sung.

Tensions between primary and secondary market players occur in art markets the world over. But the current dispute being played out in Seoul has specifically Korean characteristics.

Korea’s most venerable and established art collectors are much like their counterparts in the rest of the world — conservative, old money, with longstanding relationships with trusted galleries and institutions at home and abroad. Many are members of the founding families of the leading Korean conglomerates, or chaebol, that dominate the Korean economy: the country’s most famous private collection belongs to the Lee dynasty that built Samsung Electronics, the world’s biggest producer of smartphones and memory chips.

But the Korean market has changed dramatically in recent decades — transformed first by the rise of Generation X contemporary artists in the 1990s and, much more recently, by the rise of millennial and Generation Z collector-investors.

These new collectors reflect a transformation in the Korean economy and Korean society since the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, which hit Korea much harder than neighbouring China and Japan. Half of the country’s leading conglomerates went bankrupt during that period, a process with important knock-on implications for the Korean art market.

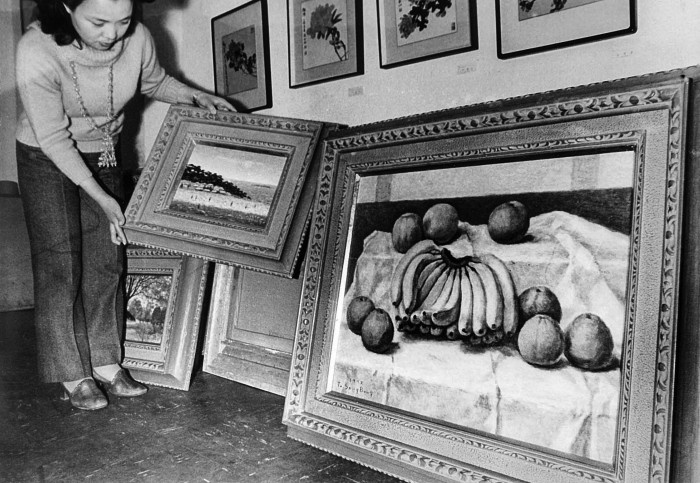

In the short term, much of the artwork being held in family and company collections was sold off in a desperate bid to raise capital. Responding to this surge of supply, in 1998 the Lee family that owns leading Korean gallery Gana Art (no relation to the Samsung dynasty) set up Seoul Auction.

That model was later emulated by Park Myung-ja, who had set up Seoul’s other leading gallery, Gallery Hyundai, in the 1970s. In 2005 Park established K Auction; her two sons run Gallery Hyundai and K Auction respectively.

The result is that Seoul’s two leading galleries and two leading auction houses are owned by the same two families — both of whom are also important players in the Galleries Association of Korea. Neither auction house responded to a request for comment about potential conflicts of interest relating to their common ownership with the country’s two leading galleries.

In the past two decades, new internationally competitive sectors including entertainment, fashion, gaming, fintech and crypto have emerged — sectors that are producing the moneyed younger Korean collectors fuelling the art market. And as the left-leaning former president Moon Jae-in placed restrictions on property investment, a lot of that money went into the art market instead.

Several Seoul-based gallery directors express concern that many of these new collector-investors are buying and trading contemporary art “like stocks and shares”. They blame local auction houses for pandering to this demand and worry that the long-term prospects of local artists could be threatened by the resulting market volatility.

One gallery director, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that there was a fear of a repeat of the excesses in the Chinese art market in the mid-to-late 2000s. “In China there was a huge boom, and prices rocketed. The artists often earned a lot of money, but they did not develop artistically and now a lot of them have simply disappeared.”

But advocates for the auction houses argue that the preference of the new collectors to enter the sector via secondary market players — for example, by buying small shares in individual artworks via online platforms — represents generational and cultural shifts with which galleries are struggling to keep up.

Jackline Byun, an art industry expert and adjunct professor at Ewha Womens University in Seoul, says younger Korean collectors “want access to market data that helps them to make their own investment decisions” rather than depending on the advice of specialists and advisers. “It is their way of expressing their own taste,” said Byun, who has previously worked at K Auction. “The auction houses allow them to do that.”

Some defenders of the auction houses also argue that many local galleries often do little to forge long-term relationships with local artists, with many preferring to act as exhibition spaces for hire. One said that the galleries are resentful because they feel they are missing out on what they regard as their rightful share of the profits from the boom. Galleries, on the other hand, argue that auction houses are “stealing” artists whose careers they have often spent years nurturing.

Clearly, what one industry veteran describes as local “power games” have not yet been resolved to the galleries’ satisfaction, even if hostilities appear to have been paused for the benefit of the industry’s foreign guests this month.

Comments