How climate change became political

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Whatever your perspective on climate change, it is likely to have been shaped by political culture and the media. For some, though, the subject is now so divisive that even the words “climate change” are controversial.

A study by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication in the US found that, in trying to encourage support for climate policies, switching to the phrase “extreme weather” was more effective in winning over American conservatives — for whom “climate change” has become a highly charged term.

This is just one example of how cultural attitudes, driven by everything from political philosophies to religious beliefs and even language, influence the ability of countries and policymakers to address climate change.

“In the political culture war, climate is one of the many dividing points that’s been amplified and exploited by certain actors,” says Anthony Leiserowitz, the Yale programme’s director.

“It’s complex,” adds Alison Anderson, a sociology professor at the University of Plymouth. “Ideology and personal values are crucial, and demographic factors like age and gender play a part — but, most importantly, it’s the political climate and the tone of the media debate that play a significant role.”

According to Andrew Hoffman, professor of sustainable enterprise at the University of Michigan, climate change is a highly contested cultural problem that tends to be seen as part of a leftwing agenda. “Once that happens, cultural projections and subtexts start to come in that drive people’s perception of it.”

This has not always been the case. For years, climate change was seen through a purely environmental lens. “It was a phenomenon happening to the natural environment that would have implications for species, and that doesn’t resonate with everybody,” says Sarah Burch, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo who studies community responses to climate change.

With the adoption of the Kyoto treaty on climate change, attitudes shifted, says Hoffman. “In 1997, what was previously a scientific issue became [one] that impacted powerful political and economic interests and the divide started,” he explains.

In the US, in particular, this prompted a wave of activity by companies and individuals in sectors such as oil and gas and coal, in efforts to avoid restrictions on fossil fuel consumption.

They tried to shape cultural attitudes, by investing in universities and think tanks and making political campaign donations. “They are really good at what they do and in how sophisticated and elaborate their tools of influence have become,” says Leiserowitz.

And, whether generated by vested interests or not, social media has turbocharged the divide in attitudes towards climate change. “People are moving into factions and social media has allowed us to become very tribal,” says Hoffman.

Today, views on climate change are often aligned with political allegiances. Last year, for example, Pew Research Center found that while 72 per cent of Democrats and Democratic-leaning Americans say human activity is driving climate change, only 22 per cent of Republicans and Republican leaners agreed.

Leiserowitz points to four countries — three of them former British colonies — where rifts over climate change are most extreme: the US, Canada, Australia and, to a lesser extent, the UK. “One of the things that binds them is English,” he notes. “That makes it super easy to transfer ideas.” However, the divide in this case goes beyond party politics, he says, and is rooted in opposing world-views: egalitarianism and radical individualism.

For those espousing egalitarianism, climate change is a huge threat “because of the effect it has not just on them but on poor people around the world and to ecosystems”. They are therefore likely to support collective action. “But, for radical individualists, the one value above all others is individual freedom and autonomy,” he explains. “People with that worldview are inherently hostile to the issue of climate change.”

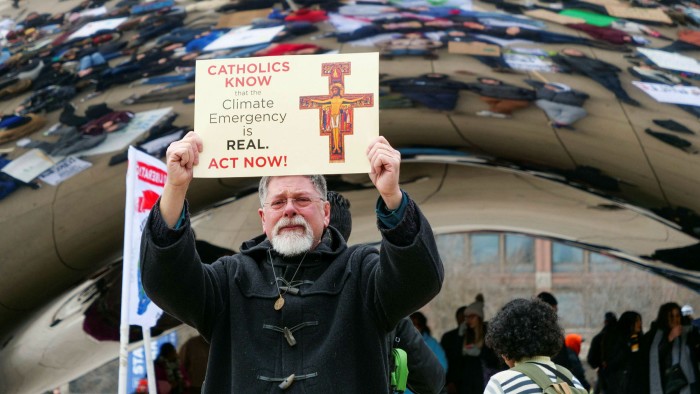

Religion also plays a critical role in shaping views, which is why September’s statement on the urgency of environmental sustainability by Pope Francis, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, and Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was seen as significant.

Cultural attitudes are generally given less attention in the fight against climate change compared to policy, business strategy and potential technology fixes. “We look to the technical elements to get us out this,” says Burch. “But the elephant in the room is that [the response to climate change] is a deeply human phenomenon and the problems and solutions are embedded in our politics and behaviours.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments