Bananas for Warhol: the pop art of cooking

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It was the most hotly contested banana in history. (OK, possibly the second most hotly contested, after the bendy variety that the EU supposedly banned.) The banana on the cover of the 1967 debut album by The Velvet Underground was an image so simple and so suggestive – especially on early editions of the LP, where the banana could be peeled open to reveal raw pink flesh inside (“Peel Slowly and See”, read the instruction) – that it could only have been the brainchild of one man: the band’s manager Andy Warhol.

Given the circumstances, it’s not surprising that the Andy Warhol Foundation, which has overseen the artist’s estate since his death in 1987, thought it owned the rights to said banana. Nor that The Velvet Underground felt otherwise, seeing as the fruit in question had become synonymous with them. So when, in 2011, the foundation licensed the use of the banana on iPhone and iPad cases without the band’s permission, a legal battle kicked off. Two years of wrangling followed before both parties reached a settlement, the terms of which remain undisclosed. None of us is any the wiser about who owns it or doesn’t. Was it a banana split?

Warhol was a big fan of bananas. He took Polaroids of them. A self-portrait from 1982 shows him eating one. He even filmed drag superstar Mario Montez licking one not once, but twice – first in colour, then in black and white. Other artists might cringe at the obviousness. Not Warhol. He embraced foods that lacked subtlety.

With a major exhibition on Warhol opening at Tate Modern in March, some might wonder if the world needs another show on him right now. But time spent with Andy rewards the effort, not least when it comes to food.

Take his 1964 work Eat. A 16mm film assembled out of sequence, it shows the artist Robert Indiana (best known for his “LOVE” paintings and sculptures) eating a mushroom. Indiana was inspired by the orgiastic eating scene from the film Tom Jones, which he had watched the night before. Ahead of the shoot, he assembled a bountiful platter of fruit and vegetables, from which Warhol selected just the one mushroom, telling him to “make it last”. (You can imagine Indiana’s disappointment: “But I bought all this papaya!”)

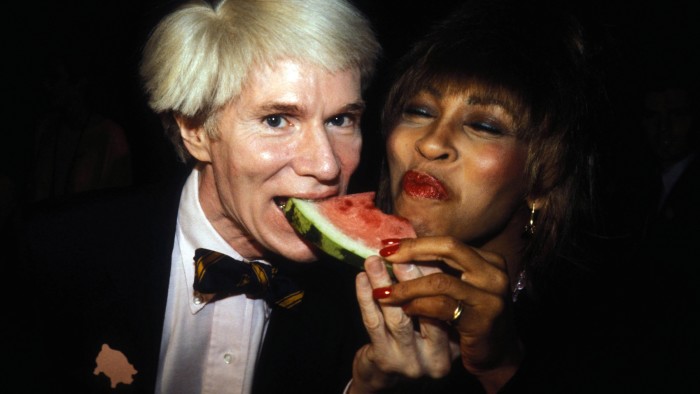

Admittedly the film, which runs to 39 minutes, has been slowed down. But Warhol shot nine three-minute rolls, which, by any measure, is a hell of a long time to be nibbling on one mushroom. Somehow, though, the film isn’t dull. Nor is it all that sexual. Perhaps that’s because what we’re watching here isn’t so much a man eating – a mushroom requires very little of that after all, unlike, say, a watermelon, the choice of which would have resulted in a very different, stickier, kind of film. What we’re watching instead is a man doing what you do when you have neither a phone nor a family to distract you between bites. Hence we see Robert Indiana looking out of the window and into the middle distance, lost in his own thoughts, his jaw moving up and down in a semi-bovine motion. Even if all he’s thinking about is his to-do list (“Must offload papaya”), it is gripping to watch.

Most of us have lost the habit, not of eating, but of eating without a sense of urgency, of really chewing our food and ruminating. It takes a 39-minute film to remind us of what we’re missing.

A lot has been made lately of the rise in solo dining, as if it weren’t largely attributable to the fact that, with a phone, no one need feel alone. Most of us would prefer the company of our phones to other people anyway. Warhol, ever prescient, solved this problem when he came up with his 1970s scheme for Andy-Mats – a chain of fast-food diners “for lonely people” where you take your tray to a booth and watch TV. He understood a fundamental truth – even singletons and loners deserve to eat out.

The only place the stigma of dining alone never seemed to apply was burger joints, and McDonald’s was Warhol’s favourite – not so much for the food but because he liked its packaging. His eye for commercial design led to some of his most famous works – the Campbell’s soup series, the Heinz ketchup boxes, the Coca-Cola screen prints – common brands with iconic logos that appealed to Warhol because every consumer in America, rich or poor, could own them. Some 30 years after his death, you can still see his legacy in the way so many foods are designed and displayed, and then exalted on Instagram.

Warhol would surely have approved of the renaissance in tinned fish in Portugal, handsomely showcased at the grocery store Conserveira de Lisboa, where shelves are stacked high with brightly coloured tins, or the fishing tackle shop-turned-restaurant/bar Sol e Pesca, where cans of sardines and tuna are served up with bread and salads.

Warhol would also have delighted in Lina Stores, the chain of Italian eateries that started 75 years ago with a deli on Brewer Street in London’s Soho, expanded to include a small restaurant round the corner on Greek Street in 2018, and last November added a larger deli-restaurant in a former warehouse behind Granary Square in King’s Cross. The latter looks like a cross between an ice cream parlour and a 1950s canteen, with candy-cane stripes and banquettes the colour of peppermint. There are even two booths with their own awnings, like you might see extending over the sidewalk outside apartment buildings in Manhattan. I like to imagine Warhol sitting in one of these, doing his sketching, as he was wont to do at Serendipity 3 on East 60th Street, his favourite “sweet spot” and unofficial headquarters as a young commercial illustrator in New York in the 1950s.

This general store-cum-café, founded by Calvin Holt, Stephen Bruce and Preston Caradine, was an apt bolthole for Warhol, full of madcap energy and a sense of its own myth. Was ever an origin story better told than theirs, by Pat Miller in the Serendipity cookbook? “It was 1954,” it begins. “The world was suffering from unrequited love, a big postwar baby boom and an insatiable craving for sweet solace. In the heart of Little Italy, sharing a cold-water flat with creepies, crawlies and things that go bump in the night, lived Serendipity 3. Princes under their frog suits, they waited, lips pursed, for the kiss that would reveal their true selves…”

Lina Stores now serves some of the best pasta in London (its crab and scallop rondini with confit cherry tomatoes is a sweet, tangy, fishy delight). But Warhol rarely ate such grown-up food. At Serendipity he subsisted on Frrrozen Hot Chocolates (the closest equivalent at Lina Stores is the Tiramisu Ice Cream Sandwich, which is like a posh arctic roll). Warhol also liked cornflakes with milk (who doesn’t regress now and again?). And when he cooked steak, which he did often, he lost interest once it was done and ended up with bread and jam. “I’m only kidding myself when I go through the motions of cooking protein,” he wrote. “All I ever really want is sugar.” Who doesn’t feel that way at least once a day?

Perhaps the ultimate Warhol food was chocolate. From an illustrator’s point of view, a chocolate bar offers the ultimate showcase, and the rise in artisanal chocolate has led to an explosion in exquisitely designed versions – Brooklyn-based Mast; Vietnamese-crafted Marou; all-female, British-led Creighton’s; or Edinburgh‑run Coco – so beautiful you want to line them up on a shelf and coo. Any of these would be perfect in Warhol’s recipe for cake. This doesn’t require the chocolate to be melted and spooned into a mixing bowl before going in the oven. All you do is lay a whole slab between two slices of white bread and, hey presto, you’re done. Tate Modern’s head chef Jon Atashroo has come up with his own version as part of an Andy Warhol-inspired menu being served at the Level 9 restaurant for the gallery’s exhibition. Joining savoury dishes that include “Tuna Fish Disaster” and “Pâté for the Cat”, the “Mars Cake” will consist of chocolate brioche Mars Bar French toast with roasted banana. My teeth hurt just thinking about it.

Comments