Multi-factor funds fall out of favour after poor performance

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Interested in ETFs?

Visit our ETF Hub for investor news and education, market updates and analysis and easy-to-use tools to help you select the right ETFs.

Years of poor performance have caught up with multi-factor funds, with more closing than launching this year for the first time in the sector’s 17-year history.

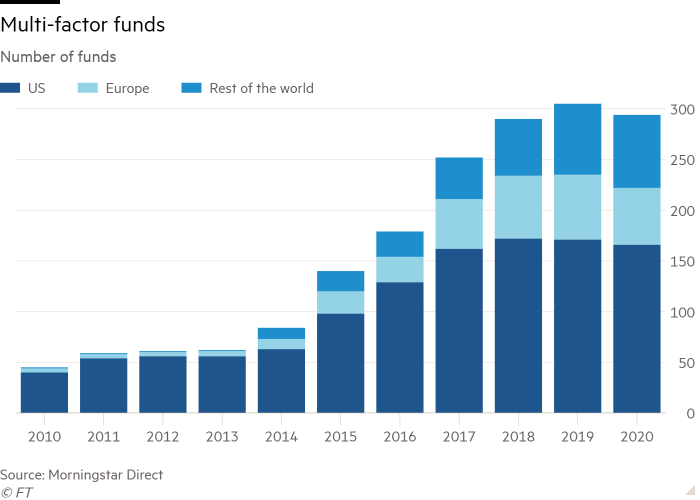

According to data from Morningstar, a record 27 multi-factor exchange traded and mutual funds closed in the first nine months of the year far outstripping the 16 launches. This is the first reversal for the category, which combines at least two investment approaches, since its birth in 2003.

Between 2014 and 2019 the number of multi-factor funds globally had jumped from 62 to 305, the bulk of them ETFs.

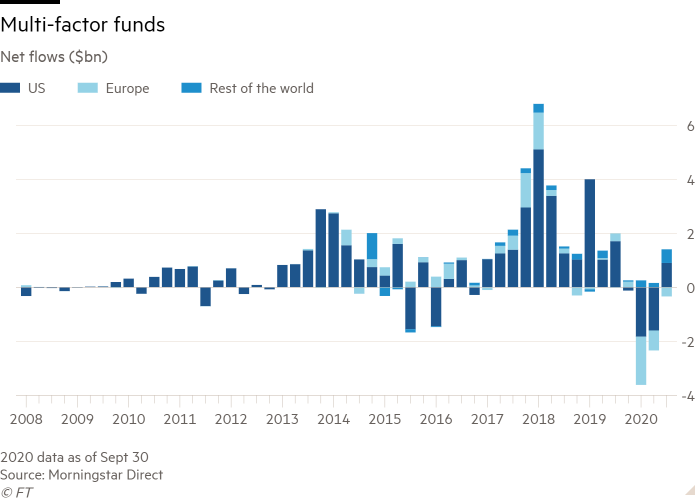

Assets, which surged from $7bn to $69.3bn 12 months ago, have since slipped to $65bn after record outflows in the first six months of 2020.

“Most multi-factor index funds have disappointed in recent years,” said Dimitar Boyadzhiev, senior analyst at Morningstar, who said that of the 91 multi-factor index funds listed in the US in September 2015, only 16 per cent had survived and outperformed their respective benchmark over the following five years.

Multi-factor funds are part of the concept of “smart beta”, which involves building portfolios skewed to “factors” that have historically been correlated with outperformance, such as value, dividend generation, momentum, small size and low volatility.

Multi-factor funds combine two or more of these elements, an approach designed to increase diversification and provide a smoother ride. They are offered by ETF providers such as Goldman Sachs Asset Management, WisdomTree, Pimco and BlackRock’s iShares unit.

However, Mr Boyadzhiev said the concept had been undermined by the poor performance of value investing, which by one measure at least is currently having its worst run for 200 years. The weak relative showing of smaller companies in the US compared to blue-chip behemoths such as the “Faang” quintopoly of technology stocks like Facebook and Amazon has also had an impact.

As a result, “most multi-factor funds have underperformed their respective Morningstar category indices over the trailing three and five-year [periods] through September 2020,” he added.

Mr Boyadzhiev said mass adoption of multi-factor funds was also being hindered by their complexity, which means “they often more closely resemble quantitative active strategies than passive index portfolios”.

For most of the past decade, multi-factor funds have consistently accounted for between 4 per cent and 6 per cent of the smart beta sector.

Consequently, in the US, which represents $57bn of the sector’s $65bn of assets, the market may simply have reached maturity, prompting fund managers to throw in the towel and close down subscale funds that had been launched in the hope of attracting significant assets.

ETF screener

Interested in finding out more? Our ETF Hub means in-depth data, news, analysis and other essential investment information is only one click away.

Outside the US, multi-factor funds are still seeing strong growth, albeit from an extremely low base, in China, where assets have almost quadrupled to $700m in the past 12 months, Morningstar said.

Amin Rajan, founder of Create-Research, a consultancy, said that while multi-factor funds might be struggling in the retail market, they were still popular with institutional investors.

A key strength is their ability to manage the correlation between different factors in a way that a series of single-factor funds could never replicate.

Multi-factor funds also have an advantage wherever performance fees are levied, in that they allow the netting of fees: an investor does not have to pay a performance fee for one factor that has shot the lights out, if another has tanked and dragged the overall performance back down.

“I would hazard a guess that we are not seeing a flight of capital from institutional investors,” Mr Rajan said. “I think this is retail investors getting out as part of a panic move,” amid the market ructions earlier this year.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments