The Fiat dynasty’s Ginevra Elkann on why her artworks are always in motion

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I don’t even know if I consider myself a collector.” That’s an inauspicious start to an interview with Ginevra Elkann, film-maker and member of the Fiat car dynasty, about how, why and what she collects. “During the years, I’ve certainly acquired art, but I don’t ever think I have thought of it as a collection. It’s rather a piece of art that I really respond to, that I respond to emotionally and aesthetically, and that I feel will make my life better.”

We are talking on the roof of Fiat’s enormous former Lingotto Factory, overlooking Turin’s southern suburbs. Film fans may know it best as the rooftop test-track from The Italian Job car chase, but to Elkann it has a deeper connection — her great-great-grandfather Giovanni Agnelli co-founded Fiat in 1899, commissioning what was then the largest car factory in the world. (It became the car company’s headquarters in 1997.) Even though she knows the building inside out, she still finds it a thrilling and unexpected place: “It has a James Bond quality — it’s got a helicopter pad and there’s a racing track, there’s something very surreal about it.”

It also has an art collection including Picasso, Renoir, Matisse, Canova and Canaletto, a 25-piece edit from the vast collection amassed by Elkann’s grandparents Giovanni and Marella Agnelli, which stars Schiele, Bacon, Lichtenstein and Klimt too. (Andy Warhol painted both Giovanni and Marella.) This selection, open to the public, is contained within the Pinacoteca Agnelli, a Renzo Piano steel-framed jewel-box of a building above the Lingotto. Elkann has been its president since 2007, and in May the Pinacoteca relaunched as a cultural centre, hosting exhibitions of contemporary art.

Under her watch, it has become a space for examining collections, exhibiting the Agnellis’ alongside others, such as those of Bruno Bischofberger or Astrup Fearnley, or pursuing a theme such as African art. Elkann says those shows were less about the individual artworks on display than the personality and passion such collections revealed in their owners: “That’s what I thought is interesting . . . This person knows everything there is to know about this, and has really focused their attention on that.”

Despite not calling herself a collector, art is present as much in Elkann’s domestic as her working environment. Her home in Rome, where she lives with husband Giovanni, their two sons and daughter — after spells in London, Rio de Janeiro and Paris — is full of contemporary works, including Pablo Bronstein and Francis Alÿs, mixed with 16th- to 18th-century paintings, Neapolitan collage, African art and paperolle reliquaries (ornate religious antique art formed of coiled and twisted paper).

She collects — or acquires — mainly painterly and photographic works, yet Elkann finds it hard to recall exactly which artists and works she has on display: they seem to exist as an extension of family and personality, not as a name on the wall or in a ledger. When pushed, names slowly emerge: “Mamma Andersson is an artist I love, and Christiana Soulou, and Elizabeth Peyton.” These artists’ works have an almost filmic sense of narrative deeper than the canvas itself. “It’s about emotion. What does art do? It opens up, shows you different ways of seeing the world that make you think.”

Does she regularly change which works are hung at home? “I’m the worst, because I hang very little actually, they lean! They’re leaning on a window, leaning on the floor, leaning here, leaning there, it’s very messy. Then I move them, and it’s a re-leaning . . . Most of them are in motion.” Her grandfather also rotated his works with regularity: his three Francis Bacon “Pope” paintings might be one day in his bedroom, the next in the basement.

Elkann says her grandparents’ collection came from “a true love for art, and the idea of having in your house these beautiful paintings that they lived with — I never really heard about the market”. She herself used to keep up with the market, visiting biennales and “art fairs everywhere” in her twenties and thirties, but due to “life happening”, that way of consuming art has passed. Describing her buying process as random, she now purchases through unexpected encounters more than strategy or search.

“Maybe I had it, but I don’t any more have any sort of acquisitive, big collector idea. It’s just, if I’m going to go to Mexico, enter an antique shop and find a beautiful sculpture — that has a value.”

Elkann is mainly known as a film-maker and producer. Having studied at the London Film School and worked with Bernardo Bertolucci on L’assedio and Anthony Minghella on The Talented Mr Ripley, she now directs features informed by the art she loves. “The way I see the image and the way I want to frame it has a lot to do with my interest in art, painting and photography.” The aesthetic of her first feature, Magari (2019), was inspired by Luigi Ghirri’s photographs of Italian landscapes; paintings Elkann owns sometimes appear as if owned by her protagonists or provide aesthetic references — her Domenic Gnoli bed painting inspired a shot in her next feature.

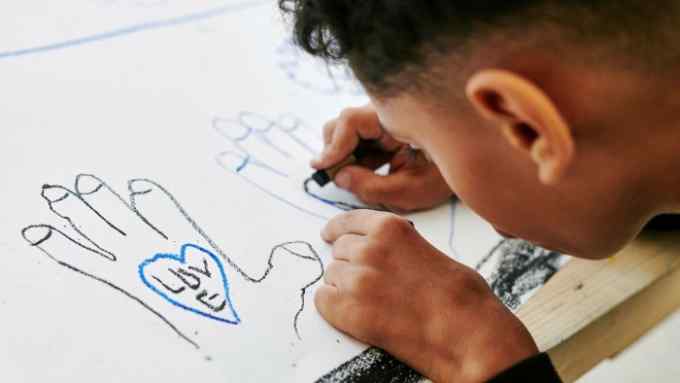

She is evidently excited about this new stage at the Pinacoteca. And now the Lingotto racetrack itself has been transformed into La Pista 500, a rooftop garden of 40,000 plants with contemporary sculptures, video and sound art — a twist on an 18th-century country garden circuit walk. A Cally Spooner sound piece resonates within a vast concrete spiral ramp; Mark Leckey has digitised the nearby Italian Alps for a video installation over a banked curve; Louise Lawler has created faux-birdcalls sporadically chirping the names of “canonical” white male artists from the undergrowth. It is a place contrasting tradition with experiment, classicism with contemporary.

With both the freshly planted rooftop and new curatorial direction set to mature over coming years, Elkann will have a new relationship to the place and collection. Having been directly involved in making the exhibitions since 2007, she will now be less hands-on. She talks about the place in familial terms: “When you have kids, you just let go, you trust — it’s about giving them the sense of place, and a sense of what the history is.”

Comments