FT Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign: Teaching personal finance with hair extensions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

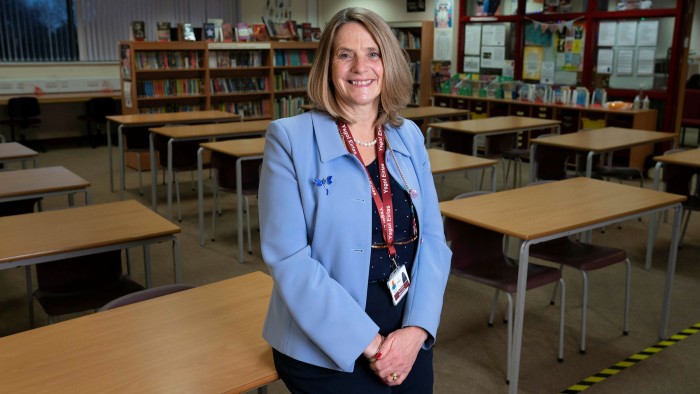

How would you persuade a teenager that learning about personal finance is worth their time and attention? For Nicola Butler, the answer was hair extensions.

The teacher at Ysgol Eirias, a secondary school in Colwyn Bay, Wales, overheard female pupils one day discussing the hair procedure, which can cost upwards of £400. “How can you afford that?” one asked. “Mum’ll put it on credit,” came the answer.

Butler was taken aback but spied an unorthodox opportunity to open a discussion with the 14-year-olds about the lure of consumer debt, interest rates and the real cost of borrowing.

It is through seizing on such conversations — using her own and her pupils’ experience of everyday life — that Butler brings home money lessons to pupils across the gamut of social backgrounds, from the wealthy to those standing in the weekly queue at the food bank. “I try to keep it as realistic as possible,” she told the FT.

This week her achievements were given public recognition, as a winner in the Interactive Investor Personal Finance Teacher of the Year Award. The annual awards give cash prizes to seven schools whose teachers have distinguished themselves as proponents of a subject that is not always seen as central to the curriculum.

The two winners — Butler in the secondary school category and Nick Redfern of Powers Hall Academy in Witham, Essex, for primary education — receive £5,000 for their schools.

Redfern initially trained as a teacher, but spent over 25 years working as an investment banker in London before moving back to a teaching role. With a high proportion of children from working-class backgrounds in his classes, he created lessons exploring the dangers of debt, asking pupils to work out which would offer the cheapest form of borrowing — a high street bank, a credit card, or a payday lender.

Showing students old advertisements from Wonga, a now-defunct payday lender, allowed him to drive home warnings about the sophisticated marketing techniques employed by lenders to attract new customers.

The judges also praised a “money personality” quiz devised by Butler, which introduced key financial concepts by exploring scenarios that pupils were likely to encounter, as well as school trips to local banks or — with sixth form girls — to the annual Women Mean Business Conference.

Butler, 53, became a teacher seven years ago, and is well placed to explain the risks and rewards of financial services having spent most of her career in finance, working for NatWest bank, asset managers and other companies.

But she also has personal insight into the hardships faced by lower-income or unemployed families. At the age of five, she was sent to a private school, but within a year her father had left the family home and her mother, saddled with debt, was declared bankrupt. She spent much of her childhood being moved around and pulled out of schools, at one point facing homelessness.

That searing experience has given her an acute sense that, even for her more privileged pupils, personal finance is an essential life lesson. “I do say to them — if things change, you have to understand that you need to be able to plan for yourself and not rely on anybody. I’m very, very aware of that.”

Another educator recognised in the annual awards was Jonathan Shields, runner up in the secondary school category. A teacher at Harrow School Online, he encouraged his pupils to take on some challenging finance qualifications. In 2009, one became the UK’s youngest ever qualified financial adviser, with a Chartered Institute of Insurance qualification. Shields is now introducing students to the Investment Operations Certificate offered by the Chartered Institute of Securities and Investment — normally the preserve of finance professionals or graduates.

FT Flic

This article is part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign to develop educational programmes to boost the financial literacy of those most in need.

Financial literacy education gives young people the foundations for future prosperity — and can help economically disadvantaged people out of deprivation. Join the FT Flic campaign to promote financial literacy in the UK and around the world

Personal finance should be a core element in every school’s curriculum, he argued. “It is a national scandal that young people do not understand credit cards, investments and all of the other basic financial infrastructure that is so critical to life as a successful adult.”

It is a need recognised by the Financial Times, which has launched a campaign to promote financial literacy and improve the prospects for millions of individuals by helping them understand how money works in everyday life.

For Butler, these lessons have become more urgent in recent years, as financial products have become more widely available to all. She recalls working in the head office of Pizza Hut in the 1980s when the finance team put through the first credit card payment for a meal at one of its restaurants. It was a different era, when credit was harder to access. “Now, suddenly, it’s just accepted. Everybody’s got credit cards,” she said.

While she worries about the temptations of putting purchases on plastic, helping pupils understand the ramifications is hugely rewarding. “Suddenly you see the penny drop. They’ll start asking questions and say ‘Oh, that’s why my Dad does that’. It’s absolutely amazing to see.”

Comments