Credit crunch: how the cost of living crisis is pushing households to breaking point

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

Russell Anderson is a man who has learned to live within his humble means. After a chronic illness forced him to retire as a coach driver three years ago, he managed to stretch his benefits to cover his bills, including rent and fuel.

Increasingly, he has found that balancing act harder to juggle. Anderson, who lives in rural Scotland, says the surging cost of fuel has made it too expensive to drive to his nearest Aldi, the low-cost supermarket he can afford, meaning he has to take a circuitous bus ride instead.

When his cat fell sick unexpectedly, there were more bills to pay. “I went to the vets, spent £170, and he came back even more sick,” says Anderson. He had nothing left to cover the bill that would have ensured the proper handling of his pet’s remains after it was put down.

Anderson’s credit rating meant he was turned down by two commercial lenders. By chance, he saw an advert for Glasgow-based community lender Scotcash on television and, to his relief, was approved for a £100 loan. He is deeply appreciative. “They bent over backwards to help me,” he says. “I’ve not got a lot of debt, and I don’t need to borrow a lot of money, but no one else would lend.”

His story is one example of the precarity now being faced by people on low incomes across the UK. With the rising cost of living stretching budgets to their absolute capacity, a single change in circumstance — from the end of a relationship, a broken appliance or the death of a pet — can be enough to push a household to breaking point.

Those with poor credit have few options when they need a small loan. One lifeline is community lenders, a small number of non-profits who support those facing financial exclusion from mainstream lending. But the sector is struggling to accommodate the growing demand. Compared with commercial lenders, their funding pot is significantly smaller; they also adhere to criteria on affordability for loans, which a growing number of customers are unable to meet.

“I would say we decline 90 per cent of applicants and that really troubles me,” says Simon Dukes, chief executive at not-for-profit loans provider Fair for You. “It’s harder now for us to find people to say ‘yes’ to as a responsible lender.”

Those working in the sector say that they urgently need more support to continue operating, let alone to scale up and match the needs of a growing vulnerable population. Many fear what will happen this winter, with the Bank of England warning of a recession and the biggest fall in household incomes for more than 60 years as the price of energy and everyday food items soars.

“Regulation, funding and collaboration are super important because it’s such a precarious sector,” says Sharon MacPherson, chief executive at Scotcash. “Think about how many businesses went bust during the pandemic: the future is never guaranteed.”

For those turned away by non-profits, the alternatives can carry more risk. Buy now, pay later products have faced scrutiny over the stringency of their affordability checks and the very last resort — illegal lending by loan sharks — opens the door to exploitation.

With the MOT on his car due for renewal and a higher energy bill looming, Anderson anticipates he will need to turn to Scotcash again before the end of the year to keep his car on the road.

The worst is yet to come

The history of not-for-profit lenders, including credit unions and community development finance institutions, or CDFIs, dates back to the late 20th century, driven by social movements in the UK and globally.

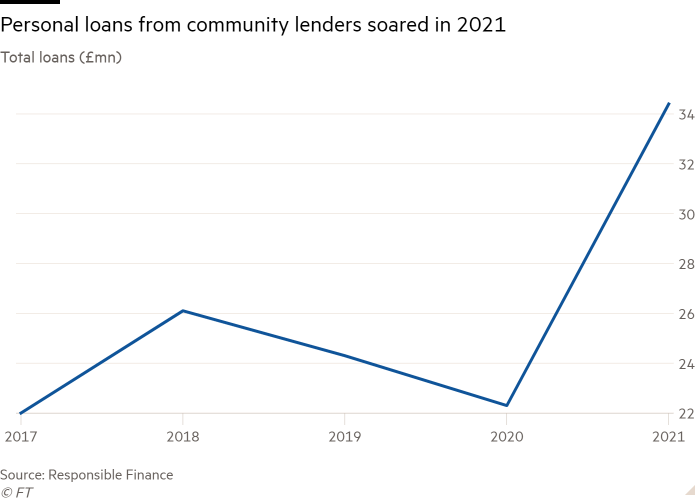

These community-focused lenders are funded by a variety of sources, ranging from grants to banks. Figures from Responsible Finance, the sector’s trade body, showed it had paid out £228mn in all types of loans in 2021 — a 32 per cent increase on the year before.

Faisel Rahman founded east London-based Fair Finance in 2005, inspired by his experience working in microfinance in Bangladesh, where it helped reduce poverty. “Everything true about financial exclusion in Bangladesh is the same in London,” he says. “You need data to assess it effectively and you have to be flexible, responsive and personable.”

Rahman has noticed that the kind of customer applying for loans has changed over time. Between 2005 and 2010, it was primarily those receiving benefits. By 2015, the dominant group were those with variable incomes, including gig economy workers and those on zero-hours contracts. Many often have less than £50 at the end of each month.

While a large proportion of customers live in deprived areas and have a median income of £15,000, Rahman emphasises this is not universal. A customer earning £65,000 turned to Fair Finance to help pay off payday loans after a missed payment.

The full impact of the cost of living crisis is yet to emerge, says Rahman. In the UK, inflation hit a 40-year high of 9.4 per cent in June, with the Bank of England predicting it will peak at 13 per cent by the end of the year, pushing up prices further. Fair Finance’s analysis suggests that later this year some customers will be unable to cover their bills and will have a negative budget even with advice on how to manage their money.

Maggie, another Scotcash customer, saw her food bill surge when her fridge-freezer broke in April, forcing her to shop daily and spend more overall. She found out about Scotcash through her local authority in 2018, and they lent £500 to support her. Maggie, who suffers from serious health conditions that restrict her mobility, has taken occasional loans from the lender since then.

The problem is exacerbated by what campaigners and community lenders call the “poverty premium”. MacPherson says the most vulnerable often pay more for fuel because of pre-paid meters, or cannot afford insurance. A number do not have their own bank accounts or savings. “They have no leeway whatsoever for putting money away,” she says. “Adding £2 or £3 extra on to a prepayment card for fuel means not being able to save it.”

Those who turn to community lenders are also least likely to access the growing number of apps designed to help customers make their money go further such as budgeting tools.

“In our experience, customers are slow adopters of these products,” says MacPherson. “When you have very little money and anything could tip you over the edge, you want to protect that as much as you can.” For those who cannot access loans, non-profit lenders play an important role in providing financial advice, she added, including by offering a digital benefits checker: “75 per cent of people are not claiming the benefits which they are entitled to,” she says. “It’s a double whammy alongside the increased cost of living.”

Credit unions, which rely on deposits from members’ saving accounts to make loans and have a cap of about 43 per cent APR set by the government, are also facing an uptick in demand.

In May, digital lending marketplace Freedom Finance said that a record 1.9mn people in the UK were now members of credit unions with total loans to members by the end of 2021 reaching £1.74bn, another all-time high. But their lending is capped by the sum of deposits they hold.

“The credit union movement in the UK is very small compared with the US,” says Robin Fieth, chief executive of the Building Societies Association, which represents a number of credit unions. “They have limited capacity to be the solution.” BSA members had warned him that it would only prove tougher in winter, when heating demand is far higher.

The importance of non-profit lenders has grown as commercial avenues have shrunk. In recent years, the Financial Conduct Authority clamped down on so-called “non-standard finance providers” that flourished after the 2008 financial crisis but drew criticism for their steep charges.

Maggie says she has used Provident Financial, formerly the UK’s largest doorstep lender (which sell loans and collect repayments from a customer’s home), but ended up repaying nearly double the amount she borrowed. Provident shuttered its consumer credit unit last year.

The number of active high-cost, short-term lenders in the UK fell by almost one-third between 2016 and the third quarter of 2020, according to the FCA’s figures.

“We know supply in the market has lessened because we’ve seen increased scrutiny and a number of lenders with poorly designed products being challenged which is, frankly, a good thing,” says Brian Brodie, chairman of Freedom Finance. “The unintended consequence is that fewer people are able to access finance.”

Loan sharks

One challenge across the sector remains a patronising and often moralistic attitude towards those without perfect credit scores, say professionals working in the sector. While people on higher incomes can access overdrafts or credit cards with competitive rates to better manage their money when times are tough, those living hand to mouth have no such safety net.

“Customers are financially savvy — there’s a common problem of people equating income with intelligence,” says Rahman. “They don’t need to be told how to do things, they need a fair option.”

Charities have warned that buy now, pay later is emerging as one area of concern. Providers of the short-term credit have faced questions around how thoroughly they check a user’s ability to afford loans, with concerns that users can load up debt across multiple providers. “Out of every 10 people we see, five or six are using buy now, pay later,” says MacPherson. “We’ve seen an explosion in that type of product, both for retail users but also daily needs, which is really unsustainable.”

While the government has committed to regulating the sector, it is only expecting to introduce new laws by the middle of 2023. After that, the FCA would have to consult on rules.

More disturbing is that a growing number of households are vulnerable to loan sharks or illegal lenders. The figure has increased from 310,000 in 2010 to 1.08mn in 2022, says Cath Williams, a manager in the government’s England Illegal Money Lending Team.

“The main reason people turn to them has always been everyday expenses — historically that’s been washing machines and school uniforms,” says Williams. “But more and more people are saying it’s to put food on the table or pay the electricity meter.”

In many cases, victims believe they are borrowing from a friend, says Williams, until they’re unable to meet their repayments. And loan sharks are getting more tech savvy with their methods of intimidation. “One illegal money lender who was prosecuted last year was using altered Snapchat pictures, with the implication that they could come around and knock on victims’ doors,” she says.

For those affected, escaping the clutches of an illegal money lender takes time. “The whole journey of realising that this isn’t a friend, then realising that this is something they need help to get out of — realising that it’s a loan shark — and then making a phone call to us is a three-year process,” she says.

Williams, whose team works closely with credit unions, says they cannot cope with demand and the numbers they turn away are rising. “As that goes up, there is a concern in terms of where people go — sometimes it’s family and friends . . . but at some point down the line they might turn to illegal money lenders, maybe as fuel prices go up.”

Case for investment

There is no single solution to protecting the non-profit lending sector, but lenders agree that ensuring a greater amount of money is available is a first step. One pathway is the dormant assets fund, a pot worth £880mn from financial assets including bank accounts, pension schemes and securities that have been untouched for a long period.

These assets, administered by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, are currently being spent on financial inclusion, alongside social investment and youth projects, with a number of community lenders benefiting from the project. In July, the government launched a consultation into what causes should be funded.

Dukes says Fair for You has been able to “grow its social impact significantly” thanks to Dormant Assets funding in 2020. “The current cost of living crisis makes the case for investment in financial inclusion even more pressing,” he says. Theodora Hadjimichael, chief executive of Responsible Finance, echoed Dukes’ sentiment, while highlighting the disparity in funding between fintechs and the non-profit sector.

“If you look at how much has been invested into buy now, pay later, and how much has been invested into high-cost commercial lenders, it’s eye-watering compared with CDFIs,” she says. “The more the government prioritises financial inclusion for dormant assets, the better.”

MacPherson also called for more local authorities to get involved. Scotcash is funded by Glasgow City Council and Glasgow Housing Association, now Wheatley Homes Glasgow. “It can be really hard to keep ahead of the curve of fintechs and ensuring that you’re relevant to customers,” she says. “We absolutely need government to build capacity of the sector.”

Tulip Siddiq, shadow economic secretary to the Treasury, says the Labour party would seek to reform legislation around the sector if elected. “Labour has pledged to double the size of the co-operative and mutual sector,” she says. “This will require regulators, such as the FCA and Prudential Regulation Authority, to have an explicit remit to report on how they have considered specific business models, such as mutuals, whose needs are too often ignored.”

The Treasury says it is supporting households with a £37bn package, including a direct payment of £1,200 to 8mn of the most vulnerable families. “We’re also backing Fair4All Finance with almost £100mn of government funding this year — a record amount — to support their work on financial inclusion, including helping people to access affordable credit,” it says.

Rahman says legislation to encourage mainstream lenders to support local communities would make a positive difference. In 1977, the US enacted the Community Reinvestment Act to ensure that banks made loans in neighbourhoods where they took deposits. “We don’t need the same [legislation as the US] but it’s crazy that there is no obligation for banks to be involved in tackling exclusion or accountable to the communities they are in,” he says.

“If you believe that financial exclusion is a problem, you have to believe that there’s a better way of doing this.”

Letter in response to this article:

Charities need same loan access as small businesses / From Sarah Gordon and others

Comments