The textile artists taking needlework to the next level

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In Tate Modern’s current collection display – positioned next to a wall of Guerrilla Girls’ posters and a bold Barbara Kruger – is a depiction of a bathroom. A woman’s legs stretch to the end of the bath; children’s toys are dotted around; there’s a glass of red wine to one side and an iPad propped up on the other, showing an episode of Game of Thrones. The scene feels at once intimate and ephemeral. Its edges slightly frayed, the work is a personal story of motherhood – mundane and magical.

Date Night is a “silk painting” by 48-year-old, Malawi-born Billie Zangewa. Described as “One of Africa’s Most Closely Watched Artists”, she joined Lehmann Maupin gallery in May 2020 with a solo show in New York that saw her prices jump by 25 per cent. This autumn, she will open further shows in London and Seoul – where prices for her work will range from $75,000 to $150,000 – as well as at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco.

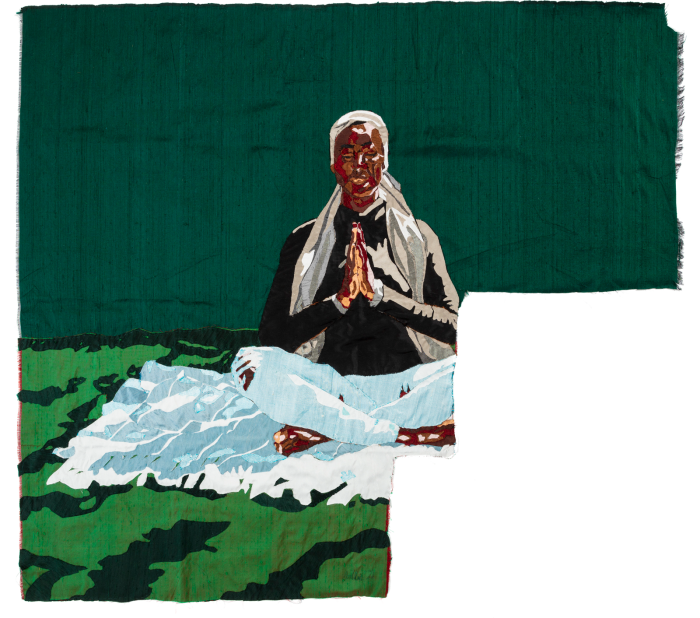

“When I first started out, people were like, ‘Oh, she’s handy with a needle’ and I was just put in the area of craft, of a woman’s pastime,” she says from her home in Johannesburg. The space doubles as her studio, and is where works such as 2018’s Vision of Love and 2020’s Heart of the Home were created. Although it was suggested she switch to cotton as a stronger fabric, she prefers to work with silk: “I like delicate and sensitive, that’s who I am. I don’t think I’ll ever be cotton. And I don’t want to be.” Re-establishing the power of textiles is fundamental: “I’m in charge of my own narrative and that’s a very powerful statement, to say that I’m a black woman and I’m in charge of my stories and how I tell them.”

Zangewa’s rise has dovetailed with a growing recognition for fabric-based pieces as fine art. At Artsy, purchases of textile works rose 48 per cent from 2019 to 2020, while a broad spectrum of fabric-based endeavours – from the modernist weavings of Anni Albers and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, to the fibre sculptures of 87-year-old Sheila Hicks and the quilts of Alabama’s Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective – have been the subject of high-profile shows. Hicks also features in the Whitney’s current survey show, Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950-2019, which positions 1960s textile art alongside the work of contemporary artists.

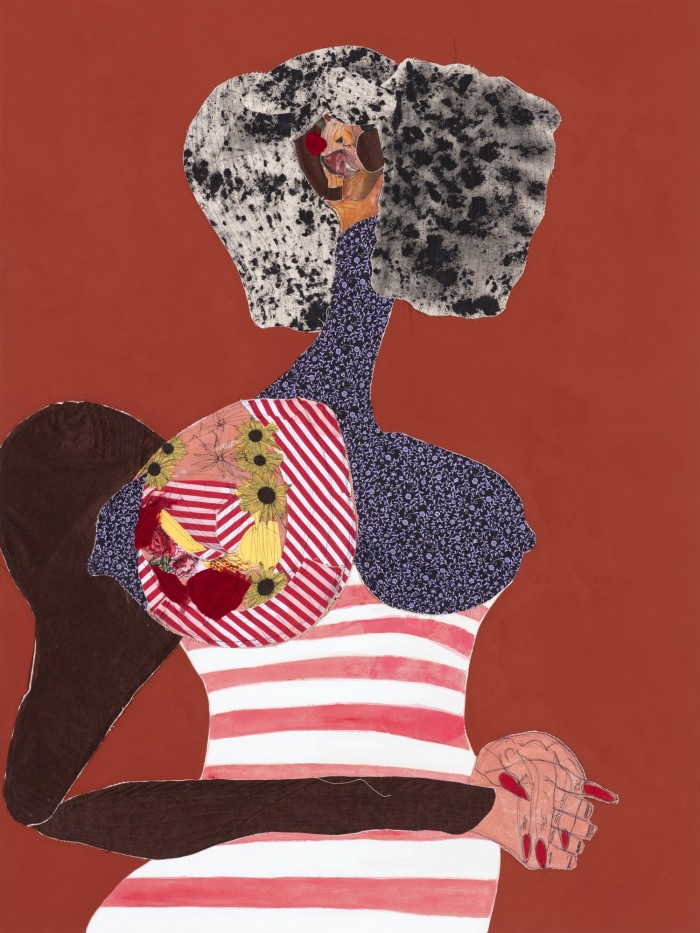

“Using textiles is not just about an aesthetic, it’s something that furthers my conceptual concerns in regard to how identities are constructed, about how a body is just a patchwork of experiences, a patchwork of projected ideas,” says 31-year-old, New York- and New Haven-based Tschabalala Self. “What’s exciting for me about textiles is that they are of the world.” Her figurative, mixed-media images – using fabrics and stitching as well as painting and print-making – first made waves in 2016, when influential art dealer and curator Jeffrey Deitch featured three of her artworks at Art Basel Miami.

Since that show, Self has enjoyed a residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem, solo shows from London to Shanghai and gallery representation by Pilar Corrias and Eva Presenhuber. Out of Body (2015), depicting two female figures, was sold by Christie’s in 2019 for £371,250 – over five times its high estimate – while Princess (2017) fetched £435,000 at Phillips last year.

“I initially thought to use sewing because my mother sewed. It’s a way to elevate her memory,” says Self of her inspiration. “My favourite pieces usually begin with me just pulling from my scrap piles, sewing pieces of fabric together with no direction in mind until something starts to form. Part of a face, the neck, and then from there I grow the figure more and more, bit by bit.” Her striking, predominantly female figures often have abstracted or exaggerated features – much has been written about the big bottoms. “My work is deeply connected to concerns around my identity politics and my love for the black body,” she continues.

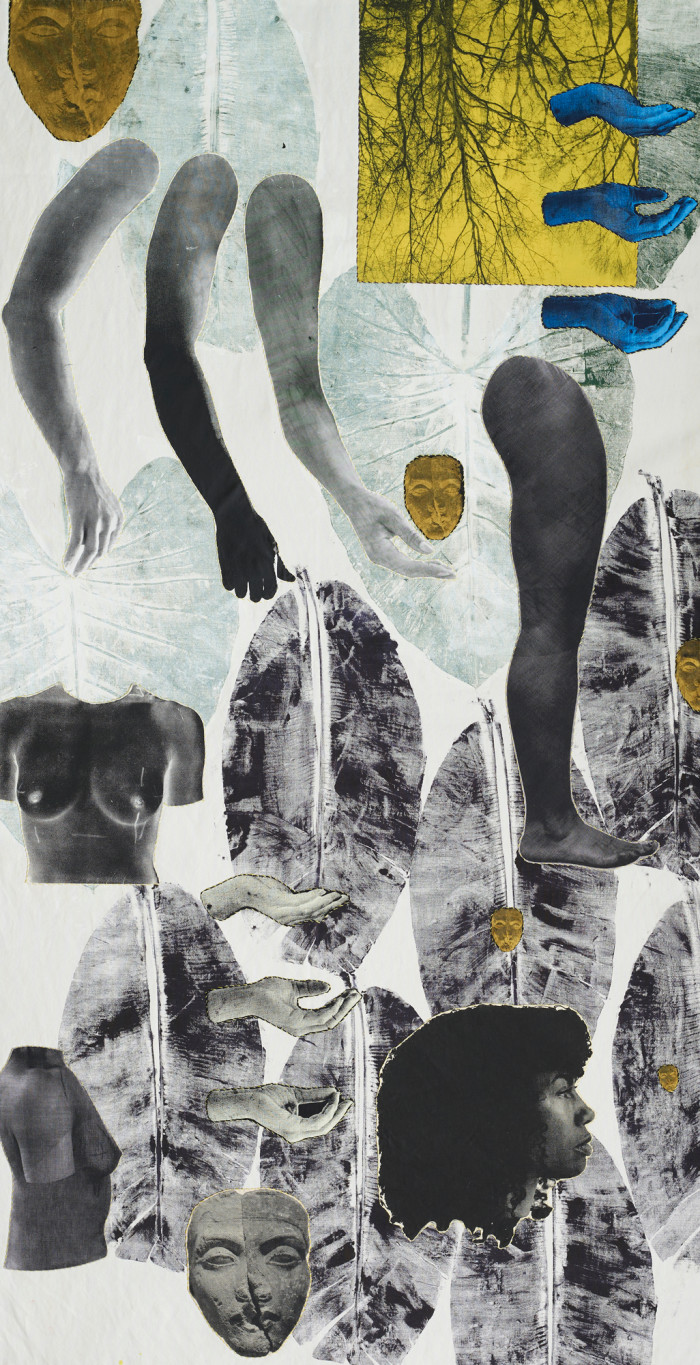

Another textile artist of the African diaspora, 45-year-old Zohra Opoku has had works acquired by London’s Tate Modern and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Working with textiles is quite a feminine space,” says the Accra-based, German-Ghanaian artist, who started sewing clothes for her dolls at age five, created whole wardrobes for herself as a teenager and studied fashion design before falling in love with screen-printing. “I was doing a residency at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht when I started printing a series of photographic portraits. I printed one onto fabric and I was like, ‘That’s it.’”

The images of people, sometimes herself, are often stitched into, sometimes hanging in ephemeral installations. “They are also a little bit layered,” she says. “And large, so that people get soaked emotionally into the work.” Textiles recur as the subject matter too, often looking at Ghanaian dress codes. “I look at how clothes define culture, at how different materials have language and history – whether it is the veil of a woman or a kente wrap of a man.” Her mostly monochrome aesthetic has recently given way to a more colourful body of work, which is currently included in Mariane Ibrahim’s group show at her new Paris gallery space.

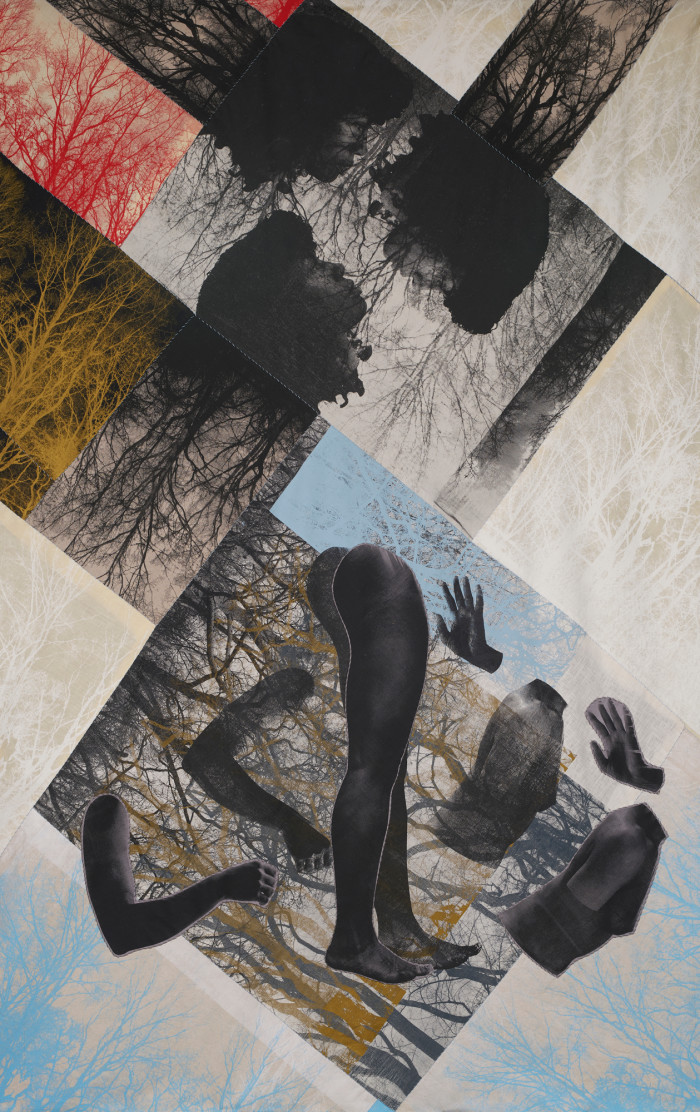

The effect of colour is instantaneous in the work of 32-year-old Diedrick Brackens, the Texan-born, LA-based artist whose textiles play with a palette of hand-dyed hues – rich purple, dusky ochre, shocking pink. At once graphic and painterly, they are inspired by west African kente weavings, 15th-century European tapestries and quilts of the American South, with the mystical and folkloric threaded into scenes that tend to centre on silhouetted male figures.

“I definitely want people to find them beautiful, but they’re also redefining what skill is,” says Brackens, who has recently modelled a Gucci poncho in the pages of VMan magazine and welcomed Rihanna into his studio. He happily straddles the realms of fine art and craft, having been awarded The Studio Museum in Harlem’s Wein Prize and also voted the American Craft Council Emerging Voices Artist; next January he will be exhibited at the Craft Contemporary museum in Los Angeles. “I feel like I belong in both camps,” he says.

Using craft mediums can be a successful way to ask people to consider a deeper story. “I think that by the time people are overwhelmed by the sentimentality, it’s too late for them to escape the messages that are present in the work,” he says. “That push and pull is one of textile’s most successful aspects. I think that there is sugar and then a trap…” In his series blessed are the mosquitoes, the “trap” is to talk about the disproportionate rate of HIV infection in black and Latino men; in bitter attendance, drown jubilee (2018), it’s the story of three black boys who drowned in police custody.

“Diedrick’s nuanced pieces explore the complexity of identity, all while engaging allegorically with American history,” says gallerist Jack Shainman, who recently showed (and swiftly sold) eight new weavings in his New York space. “You can feel his intention and hand across his entire artistic process – from the spinning, dying, and weaving of cotton, to the way he inserts himself into some of the work.”

In a conversation with writer Danez Smith, Brackens said he is interested in “creating a mood”, giving the viewer works without “a wall label that tells them where I’m from and what these symbols might all mean”. When he posted about his New York show online, he accompanied an image of his work a season without gravity with lines of his own poetry. It is a reminder that while there may be a linguistic link between “text” and “textile”, the stories interlaced in contemporary textiles are rarely linear.

“It’s about one individual being a sum of many parts,” says Self. “Through honestly investigating your own life, your own fears and desires, you are able to find something that everyone can identify with. It’s about finding something unifying.”

Comments