The Château that fired Picasso’s imagination

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

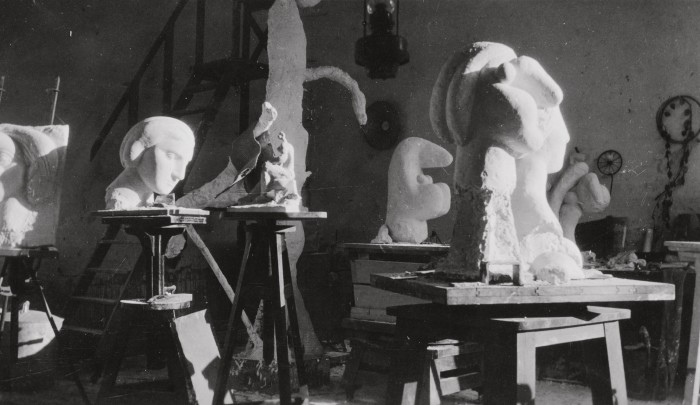

In 2016, the Musée Picasso-Paris hosted the exhibition Picasso. Sculptures. A recurrent detail appeared throughout the exhibition – a château called Boisgeloup, which appeared on labels under several plasters of Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s mistress, notably the Tête de femme (1931-32) and Buste de femme (1931). I was intrigued. It was at this 18th-century château in Normandy that Picasso threw himself into sculpture, a form of expression for the artist that – surprisingly – remains one of the least celebrated parts of his legacy.

In the 50th year since the death of the Spanish artist, I’m visiting Château de Boisgeloup. I take the train from Saint-Lazare in Paris to the town of Gisors, about 45 miles north-west of the capital, where I find Bernard Ruiz-Picasso – grandson of Pablo Picasso and Olga Khokhlova, and son of Paulo – waiting for me, all geared up with his felt hat, muddy leather boots and a khaki windbreaker that keeps out the freezing cold.

Behind him is the shiny black Hispano-Suiza H6B that Picasso acquired in 1930 and which his grandson now uses to dart around. Picasso always refused to drive himself, for fear of “ruining” his hands, as he told artist Georges Braque, as recounted by art historian John Richardson in Un Soir à Boisgeloup (2013). So while the car interiors – lacquered venous wood, cream wool seats that feel as though you’re lounging in a salon, and giant metal steering wheel – have been refurbished, my passenger seat is still the spot where Picasso sat (or, indeed, his sculptures – some of which were brought to Paris to protect them at the dawn of the second world war) during his many journeys between Paris and Normandy.

“My grandfather was looking for a place to develop and delve deeper into his experiments with sculptures,” says Ruiz-Picasso as we drive through the oak gates to Château de Boisgeloup. “He had already been to Fontainebleau, south-east of Paris, in 1921, but he had more knowledge of the Normandy region, which had more culture back then, with its many poets and artists – such as Claude Monet, who lived at Giverny. It was not too far from Paris and, with its openings onto the countryside, and its former stables, which offered the possibility of a studio on the ground floor, seemed perfect.” Picasso bought the property in June 1930 and arrived soon after with Olga and a nine-year-old Paulo.

The three-storey château, with its terracotta tiled roof and blond stones, is surrounded by a sumptuous 30-acre park all bathed in Normandy’s crisp light. Facing it is a 14th-century chapel, a mix of gothic accents and 19th-century stained glass. And next to that, an enfilade of stables, among which sits Picasso’s former sculpture atelier: the old wooden ladder he used to reach the top of his monumental sculptures is still visible inside.

“The house was built out of the stones of a castle that burned down in the 18th century,” says Ruiz-Picasso’s wife, the gallerist Almine Rech. “It was not equipped with electricity or heating, but Picasso was so eager to invest in the place that he moved in. Olga sought help from her friend Coco Chanel for the furniture and interiors,” she continues, showing me some furnishings – wicker chairs and some Louis XVI pieces – that are still here. From 1930 to 1935, Boisgeloup was a primary place of creativity. “When he was not in his studio, Picasso would host art dealers from Paris, and friends such as the artists Georges Braque, Élie Lascaux and Giacometti. And when Olga was in Paris, his mistress Marie-Thérèse would visit Boisgeloup.”

“I saw him with the eyes of a child. He always had famous people visiting, talking about serious matters,” recalls Bernard, who has particular memories of mopping his grandfather’s brow with a cold cloth during warm summers. When Picasso passed away in 1973, Bernard’s father, Paulo, inherited the estate. But just two years later, Paulo died, leaving Bernard, then only 14, at the helm.

It took some time for Bernard to understand its significance, even though it was where he had spent happy holidays with his family. “It was only many years after his death that I realised that I was born amid a kind of mythology,” he says. “Only then did I want to understand what Picasso represented, and what he represented within a complex history.” In 2002, he and his wife founded the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso (FABA) as they continued the restoration of the château.

On the ground floor is a wooden-beamed kitchen traversed by light (from which now comes the smell of cheese, leeks with vinaigrette, and omelettes that are being prepared for us); the dining room, with its clementine walls and chairs upholstered in blue and orange, mimicking the hues of the lozenge shapes in the carpet; and the grand yet sparse living room, where Picasso’s 1921 painting Trois femmes à la Fontaine used to hang. These rooms were all lightly refurbished in the early 2000s with the help of designers Élisabeth Garouste and Mattia Bonetti. Upstairs are the bedrooms, off corridors with red tomettes floors. Alongside a monumental tapestry by Picasso, based on his 1938 Femmes à leur toilette, artworks by Julian Schnabel, Franz West, Jacques Villeglé, George Condo and Miquel Barceló adorn the house that Ruiz-Picasso and Rech use as their getaway from Paris – somewhere they escape to with their two children and Almine’s two children from a previous marriage.

During the restorations, “so many painting tools and musical instruments belonging to Picasso were found in the attic,” Ruiz-Picasso tells me. The house still acts as a treasure box holding the artist’s secrets from this period. In Olga’s bedroom on the ground floor, and, above it, Picasso’s painting studio, you can sense their former owners; the floors of the latter are still constellated with the artist’s paint. It was here that Picasso drew his erotic and whimsical oil on canvas Le Rêve in 1932; here too he drew the view of the chapel and the dovecote wrapped under a rainbow. Today, as we peer through the window, the scene remains the same.

In 2012, there was a shift of gear for the foundation. “As we were spending more and more time in this house, Almine thought this place – at the least the studio – deserved to be opened to the public,” recounts Ruiz-Picasso. Though “initially resistant”, he was persuaded, and in October, FABA organised the first contemporary art exhibition at Boisgeloup, Un Soir à Boisgeloup, showing sculptures by Franz West, Cy Twombly and David Smith – set up in conversation with Picasso’s Head of a Warrior (1933). Since then there have been exhibitions almost every year.

FABA works along four pillars. “We study and preserve Picasso’s work; we organise exhibitions, and we support contemporary artists – because Picasso himself always backed other artists,” says Ruiz-Picasso. As well as shows at Boisgeloup, FABA also organises exhibitions elsewhere: one show pairing Picasso’s work with that of Richard Prince was hosted at the Museo Picasso Málaga.

The grounds of Boisgeloup are also filled with permanent installations of contemporary art pieces. In the cour is a bronze sculpture by Per Kirkeby, while atop a small hill in the park, Triangular Solid inside Triangular Solid (2002) by Dan Graham reflects the château back at itself. A 1995 installation by American artist Lawrence Weiner on the façade of the stable reads, in thick blue paint: “A line drawn from the first star at dusk to the last star at dawn.” The sentence seems to have been crafted for this place that weaves the past with the present, and where the legacy of Picasso is so carefully watched over that one imagines the artist’s spirit still present throughout its many rooms.

“We started FABA because we realised, over time, that we had many show ideas, and were lending art to exhibitions and museums as personal loans, sometimes almost 500 a year. Structuring all of those activities under the umbrella of a foundation, a non-commercial entity, made perfect sense – now all the loans from the Picasso collection go through FABA,” says Rech. This year, the role of FABA has become even more fundamental. No fewer than 50 shows and events will commemorate Picasso’s art, from a Paul Smith-curated exhibition of the artist’s objets in the Musée Picasso-Paris, to a symposium on “Picasso in the 21st century” at Unesco’s Paris HQ in December. Each exhibition will tackle a different facet of the Spanish master. His relationship to prehistory is explored in an exhibition recently unveiled at the Musée de l’Homme. And while the Musée Picasso in Antibes will dedicate a show to the last years of his life – Picasso 1969-1972. La fin du début (opening 8 April) – Young Picasso in Paris will be hosted by the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York, opening 12 May. Some of these events will question nuances of Pablo Picasso’s work, such as a collaborative exhibition with the Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby that is opening at the Brooklyn Museum on 2 June.

Pablo Picasso has never felt so immortal, so eternal, as he does in this anniversary year. “Our mission is certainly to safeguard my grandfather’s legacy,” concludes Ruiz-Picasso, in unspoken agreement with his wife. “But also to pursue his adventure and place him at the heart of the 21st century.”

Comments