Bloom raiders: the secret world of the everlasting flower

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Rebecca Louise Law’s installation is unveiled at the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Florida next summer, it will consist of more than one million flowers – all carefully collected, preserved and repurposed over the past 17 years. “I do not throw any flowers away. When they turn to dust, I keep the dust,” says the Snowdonia-based artist, whose ethereal floral displays have graced venues from San Francisco to Melbourne, and been commissioned by brands including Hermès, Jimmy Choo and Dolce & Gabbana.

Paintings, particularly seascapes, were Law’s métier before she began to experiment with 3D forms and organic material. Her love of flowers, however, was inherited at an early age from her father, the head gardener for Cambridgeshire National Trust property Anglesey Abbey. “The flower is my medium, my paint, and the space is my canvas.” Her work involves a combination of fresh blooms, which dry in situ, and preserved flora – from roses and dahlias to poppy heads and thistles to herbs, grasses and pine cones – often suspended in the air with copper wire. “I’m drawn to the fragility and deep tones of dried flowers,” she says. “For me, they depict time. They have growth and life ingrained into every surface.” Earlier this year, Law explored the concept in an intimate installation called The Womb at Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park in Michigan, its dense floral canopy designed to elicit the sensation of being cocooned in nature.

Whether she’s creating huge installations or smaller sculptures encased in Victorian-style vitrines, Law always focuses on sustainability – a key factor behind the recent reappreciation of once-fusty dried flowers. Interest in preserved blooms has shot up; earlier this year, handmade marketplace Etsy UK reported that searches for dried flowers had increased 93 per cent in just six months. Florists such as Grace & Thorn in London and Floriade in Wellington, New Zealand, are also seeing increased demand. “Half of our sales are now dried flowers,” says Floriade owner Annwyn Tobin. “The rise has been incredible.”

For London plantswoman Kitten Grayson, longevity is only one dimension. “We want people to know where the flowers come from and use any waste as compost to create a very beautiful cycle,” says Grayson, who is currently setting up her own cutting garden in Somerset to create a traceable and diverse supply for the theatrical displays she dreams up with creative director Harriette Tebbutt. Their dried-flower installation at Hampshire hotel Heckfield Place is a striking example. It hangs from the dining-room ceiling and is ever evolving, with new elements added each season from the hotel gardens.

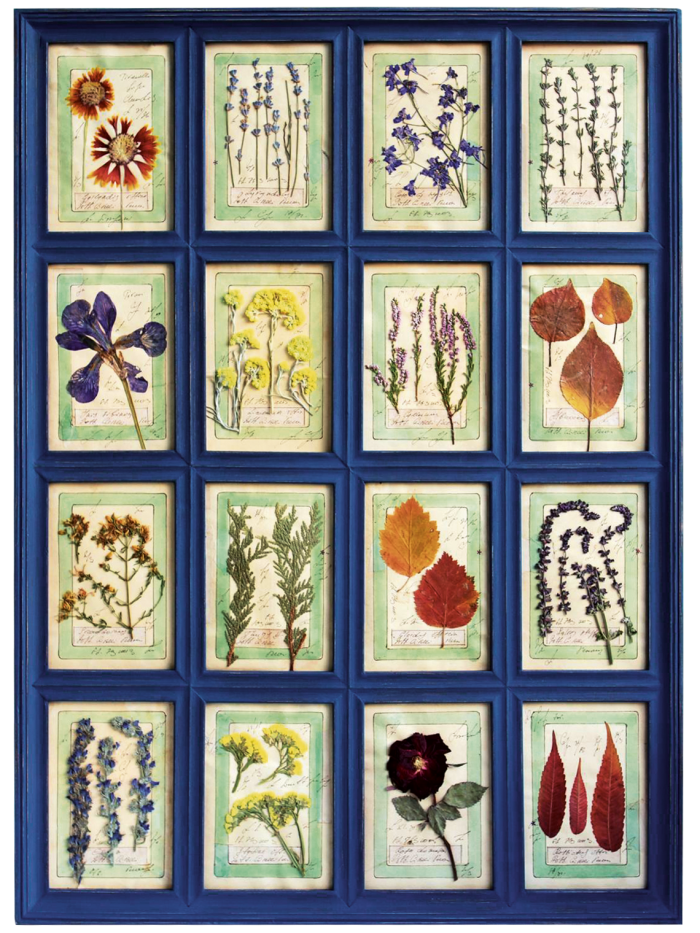

The art of pressing flowers is another Victorian pastime being revisited. Antiques dealer Alice Wawrik, who trades as By Alice, puts together framed herbariums of annotated vintage specimens. Mike Pollard and Rika Yamasaki of MR Studio London create artworks from pressed flowers and plants they either grow or forage, providing “a different sense of beauty to something more traditionally revered in a bouquet or garden”.

Florist Melissa Richardson, whose work has been displayed at Mayfair restaurant Sketch, favours flowers more typically considered weeds for her press. “We follow instructions written by botanist Joseph Banks in 1770, when he was collecting specimens on a voyage with Captain Cook,” says Richardson, who founded botanical lifestyle brand JamJar Edit in 2017 with creative director Amy Fielding. In 2018, they undertook a dream commission to create a wall of pressed flowers with specimens picked from the land around the client’s Dartmoor home.

Richardson also encases pressed flowers in clear resin to create eye-catching coasters. This technique is taken further by Irish artist and furniture maker Sasha Sykes, who captures pressed and dried wildflowers and colourful hydrangeas in bold resin forms – from lamp bases to table tops and folding screens. And since 2014, Polish artist Marcin Rusak has been taking flowers that otherwise would be discarded by florists and setting them into black or white resin. He cuts this composite material into slices to reveal fossil-like cross-sections in his Perma pieces, while his Flora Temporaria tables and cabinets use whole flowers in surfaces resembling 17th-century Flemish paintings. “Flowers are suffused with meaning and symbolism, and have become a vehicle to speak about ideas I care about, like consumption and value,” says Rusak, whose mother and grandfather were both flower growers in Warsaw. “Cut flowers are constantly in the process of fading. The struggle between decay and preservation is comparable to life in general – and I love to visualise this in objects.”

Rusak’s organic objects are part furniture, part sculpture. His latest Perma collection is constructed from sheets of milky-white “bio-resin”, which slot together in abstract yet still functional configurations. He’s also experimented with flower-infused glass, creating a series of vessels in which the molten material transforms the flora into “half-incinerated shapes of their previous selves”. The inclusion of ephemeral material gives the glass forms intriguing pattern and texture. “There’s a certain type of beauty connected to transformation,” he says. “It makes a break with the common-sense notion that what decays needs to be thrown away and replaced.” Creating permanence from the disposable – and beautifully so – is what makes all these preservation projects feel so utterly fresh.

Comments