Do or dye – the shibori crew leading the Japanese youthquake

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

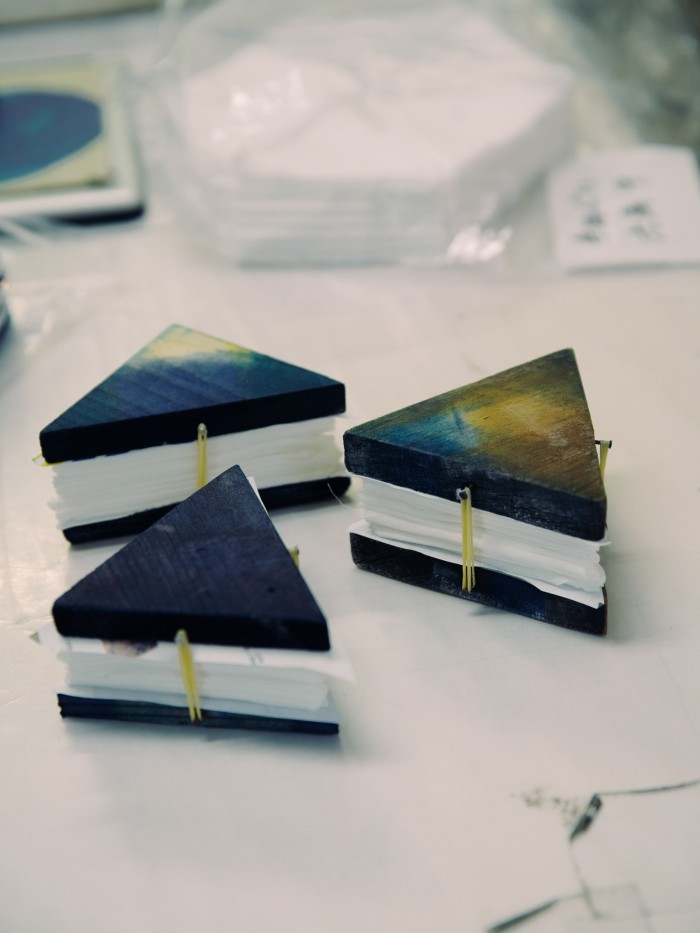

Hiroyuki Murase grew up surrounded by shibori, one of the country’s oldest dyeing techniques dating back to the 8th century. His hometown, Arimatsu, was and still is seen as the country’s shibori hub: much of the intricate pattern-binding and tie-dyeing process was done in the family kitchens and living rooms where children like Murase ate their dinners and did their homework.

Before the second world war, Murase’s father Hiroshi estimated that there were more than 10,000 shibori artisans in Japan. By 2008, when Murase decided to continue his family’s century-old legacy, the figure had dropped to fewer than 200. Postwar industrialisation and globalisation dampened demand for traditional crafts, while young graduates aimed for stable corporate jobs. At one point, despite being in his late 50s, Murase’s father became the youngest shibori artisan in town.

“Everyone in the village thought there was no future for shibori, that there’d be no next generation,” says Murase. Not only were artisans ageing and the culture of wearing traditional garments like yukata and kimono on the decline, but each family had its own, unique design – a crest of sorts – and whenever one family stopped, a technique would be lost. The fact that Hiroshi’s textiles were used by local luxury labels like Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake did little to assuage the sense of foreboding; much of the business was wholesale.

More than a decade later, Murase’s business has taken an unexpected turn. His own brand Suzusan, which launched in 2008 as a luxury fashion and homeware label aimed at giving the craft and his family business new focus, has attracted retailers such as Farfetch and Japanese department stores Isetan and Takashimaya.

Suzusan – which features bright, luxe cashmere and cotton pieces with relaxed silhouettes – is appealing to a new generation of creators. The youngest employee, Ryoga Ota, who joined the brand in 2020, is only 18; the average age of the Japanese team is 35. With help from these members, Murase – who is now based in Düsseldorf – draws shibori patterns on his iPad for employees in Arimatsu to use as guides, allowing him to avoid travelling back and forth between Germany and Japan. “I started the brand because I wanted to bring the tradition to the next generation, before it was gone,” says Murase. He now believes he’s achieved that goal.

Murase attributes the growing interest to the growing disillusionment with the corporate world and a desire among young people to lead a more balanced and meaningful life. “People in Japan believed that if you worked for Sony, Panasonic, Toyota, you could work there until you’re 65… that your life is safe,” he adds. “But during the pandemic, we saw huge companies go bankrupt… past definitions of success don’t mean anything anymore.”

One of Suzusan’s employees, Noriyoshi Yamauchi, joined the brand after leaving a major carmaker. His story aligns with studies by Susanne Klien, associate professor of modern Japanese studies at Hokkaido University, who for more than a decade has observed younger Japanese people leaving major cities to lead quieter lives in rural towns. The country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication found that more than 400,000 people left Tokyo in 2020. Says Klien: “[The pandemic] has really pushed people who’ve been thinking of it to have a different lifestyle. It’s a paradigm shift.”

In her 2020 book Urban Migrants in Rural Japan, Klien spoke to a number of people who had “broken their bodies” (karada wo kowashita) and suffered mental breakdowns before moving away or opting out of lifelong office jobs. Despite having advanced university degrees and education, she found many of her subjects were exploring more creative and stimulating work options, joining a venture or starting internships, and often working several jobs at once.

At present, the youths shunning corporate norms and city life are still a minority. Still, says Klien: “Some people dismiss it and say everyone will go back to Tokyo eventually, but I don’t think so.” The availability of remote work, and the fact that the government is working to decentralise its population in the event of natural disasters, suggest that the patterns starting now will be felt in the long-term.

For Murase, this shift has rejuvenated his workforce and their way of working; he notes that other small family businesses in the area, producing Urushi lacquerware and Owari Shippo enamelware, have also benefited from an influx of younger hires.

Shoppers, too, are gravitating towards items that are traditionally crafted or handmade, says Hirofumi Kurino, co-founder and creative adviser of Japanese retail group United Arrows. “If they see [traces] of handicraft or artisanal work, our customers love it.” Kurino sees the growing appeal of unique, well-crafted slow fashion as an example of what he calls the “post-luxury” consumer world.

The term isn’t limited to traditionally crafted objects. “Post-luxury is more human, more honest, more raw, more naked,” says Kurino. A major component is the mounting awareness around sustainability, including the dangers of mass production and overconsumption. Unlike many countries around the world where small artisanal businesses have largely been wiped out, Japan still has an active infrastructure of artisans and businesses to cater to demand.

Now that Murase is attracting younger employees, he’s focusing on helping them learn shibori, which can take up to a decade to master. But despite diminishing interest in lifelong, stable employment, Murase isn’t worried about staff working at Suzusan for shorter stints. “I often say to my staff that they don’t have to stay at one company. They’re free to choose their own life.”

Comments