Collapse of Bulb highlights failings of UK’s retail energy sector

Simply sign up to the UK energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On a breezy summer’s day in July as Boris Johnson sat on the terrace of the headquarters of Bulb in Bishopsgate, London, he was full of praise for Britain’s seventh-biggest energy supplier, describing it as a “wonderful company” that offered customers 100 per cent renewable electricity.

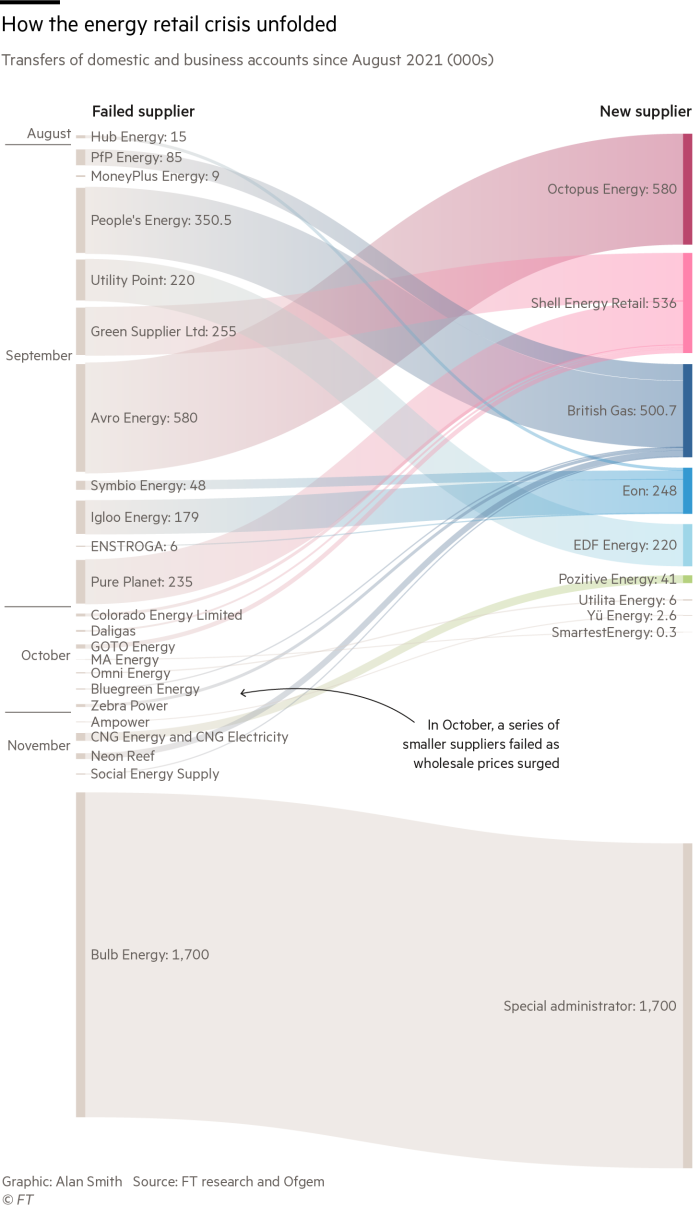

“Seems incredible to me,” the UK prime minister commented, as he toured the premises of the company that first entered the market in 2015. And so it proved on Monday, when Bulb became the 23rd victim of the sharp rise in energy prices since the summer, affecting 3.7m customers in total.

Up until now, affected households have been quickly transferred to rivals under an industry rescue scheme, financed by a levy on bills. But Bulb’s size — with 1.7m customers, it is the biggest supplier to fail in 20 years — means it will enter “special administration”, the first use of the mechanism since it was introduced in 2011.

Bulb will be run by administrators on behalf of the government until it is sold, restructured or its customers are transferred to its other suppliers. The taxpayer will foot the bill, which is expected to run into hundreds of millions of pounds.

But with more failures anticipated this winter, analysts have warned that the total cost to the Treasury and energy bill payers would run into billions of pounds.

The crisis has prompted consumer groups, politicians and industry executives to call for urgent action in a sector that had 50 domestic suppliers at the end of June.

“When the country’s seventh-largest supplier fails, serious questions must be asked about the state of the market and how it’s regulated,” said Gillian Cooper, head of energy policy for Citizens Advice.

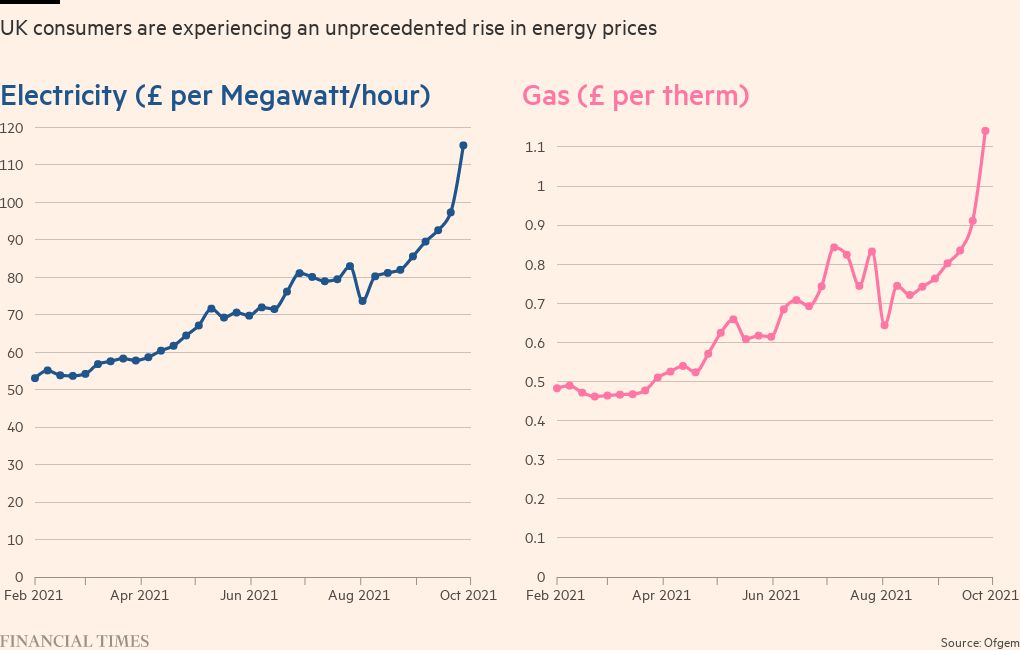

Industry executives have long argued that the regime is too light touch for failing to assess the liquidity of new entrants sufficiently and whether their financial model could withstand price shocks. Suppliers are bound by a price cap covering about 15m households that is reviewed twice a year, which has restricted their ability to pass on the rising wholesale energy costs to customers.

The cap was introduced only in 2019 by Theresa May’s government after years of pressure over “rip-off” energy bills. The regulator Ofgem reviews the cap twice a year, with the next change not due until April.

Meanwhile, ministers have made it clear that they do not intend to intervene. “Later, we will have to look at regulatory reform, but the priority now is to protect consumers, not companies,” an energy department official said.

The chief executive of one large supplier said action should have been taken sooner, pointing to the “glaringly obvious” holes in the oversight of the sector as far back as 2016, when a rise in wholesale prices led to the collapse of the first new entrant GB Energy. “This is a spectacular failure of regulation,” he added.

Larger suppliers in particular have long complained that regulators and politicians had encouraged a “race to the bottom” on energy prices. Amid a clamour from politicians to cut energy bills, the regulator has since early in the past decade encouraged new entrants to break the power of what were then known as the Big Six suppliers: British Gas, EDF, Eon, ScottishPower, Npower and SSE. The last two have since exited the market.

But the newcomers often took on customers at a loss to win market share. Many gambled that wholesale energy prices would not rise and had inadequate hedging strategies to protect themselves.

Andrew Lindsay, co-chief executive of Telecom Plus, which owns Utility Warehouse, the 10th-biggest energy supplier, said the failures came as no surprise. “All that has happened in the last 10 weeks is what I call the final blow, to what was an existing inevitable trend.”

Some suppliers are pushing for much tighter regulation akin to the financial services sector. That would include more rigorous checks on financial models and protection of customer credits.

“We shouldn’t accept suppliers that aren’t properly capitalised and who are effectively gambling with customers’ money rather than investing their own equity,” said Michael Lewis, UK chief executive of Eon, the second-largest supplier.

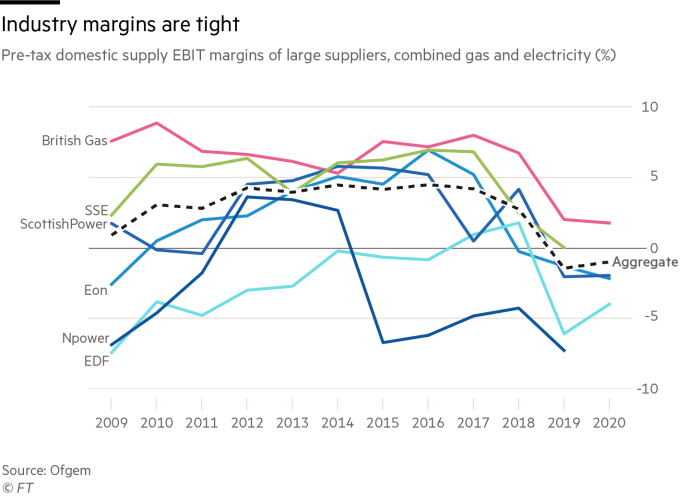

But industry executives also want ministers and the watchdog to recognise that they need to be able to make a sustainable profit and complain that the price cap is too inflexible. Figures from Ofgem data show the biggest suppliers on aggregate were unprofitable last year.

John Penrose, a Conservative backbench MP, who was one of the leading campaigners for a price cap before its introduction, admitted on Tuesday that politicians had got it wrong.

“We are where we are today due to mistakes made by parliament — it was the wrong type of price cap,” he told a podcast run by energy supplier Utilita.

Last week, Ofgem set out proposals to allow it to raise the price cap more often in the event of “unprecedented market changes”. But it must follow the regulatory process and consult on any changes, which will take until February.

It also said it would look at more stringent vetting of companies by “exploring a move towards prudential regulation, recognising that energy suppliers are managing complex financial risks”.

Meanwhile, politicians are turning the turmoil in the sector into a political blame game as it plays out against a broader cost-of-living crisis after recent tax rises, and with energy costs just one factor driving inflation higher.

Labour’s Ed Miliband, the shadow business secretary, blamed the collapse of suppliers on “a decade of Conservative inaction in government which has left us exposed and vulnerable as a country”.

But one government official said Miliband was himself partly to blame, as before the 2010 election he had as energy secretary left “90 per cent of the country . . . trapped on Big Six contracts”.

It was the Conservatives who had “introduced much more competition in the market that has driven down costs”, he said, insisting that the price cap had done its job. “It has been largely private companies which have sustained losses in recent months rather than taxpayers.”

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Comments