Computer art enters the mainstream with Lacma’s Coded show

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 1968, the Californian abstract painter Frederick Hammersley was at an impasse. He had just moved from Los Angeles to Albuquerque, to teach at the University of New Mexico, and he felt stuck, artistically. “I had painted myself out,” he later said.

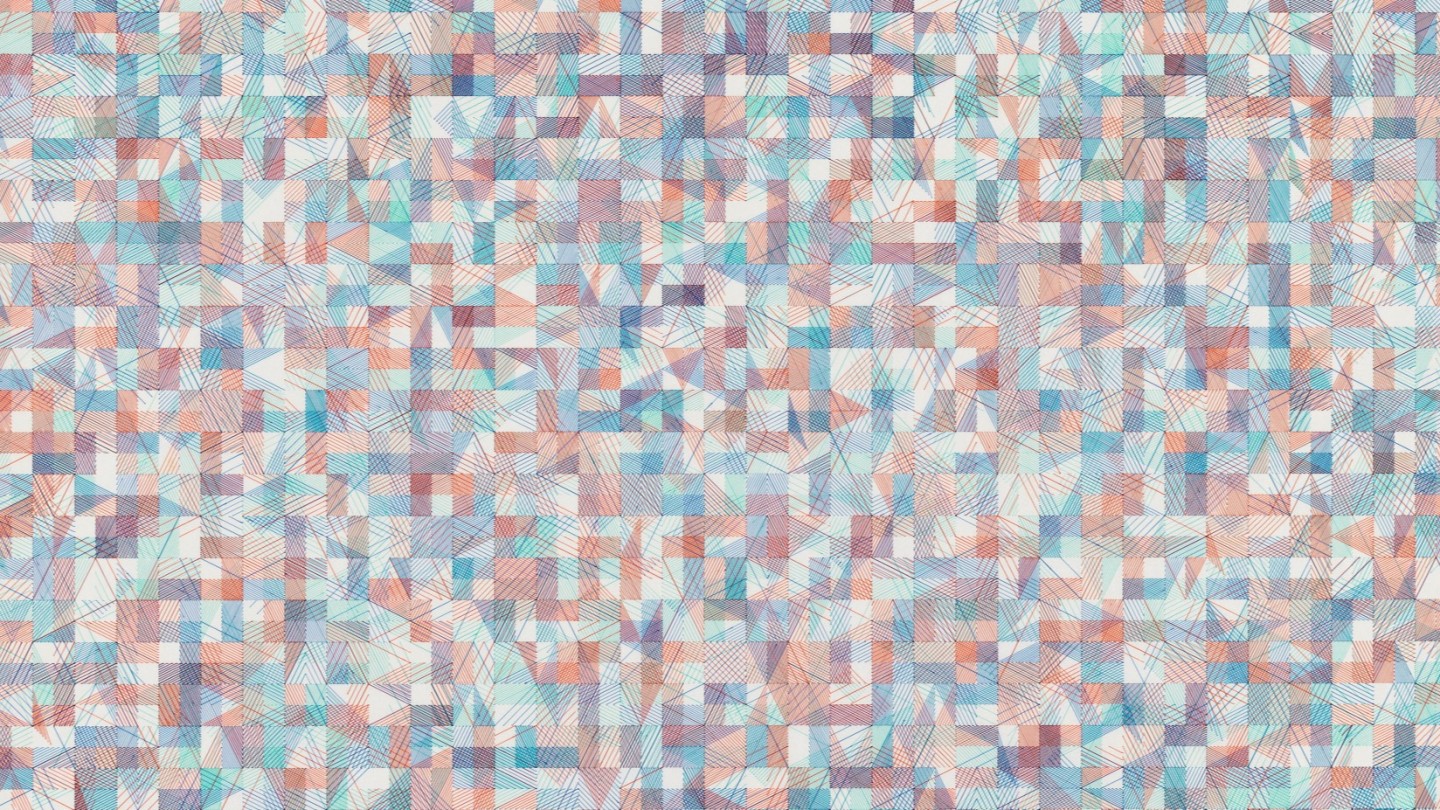

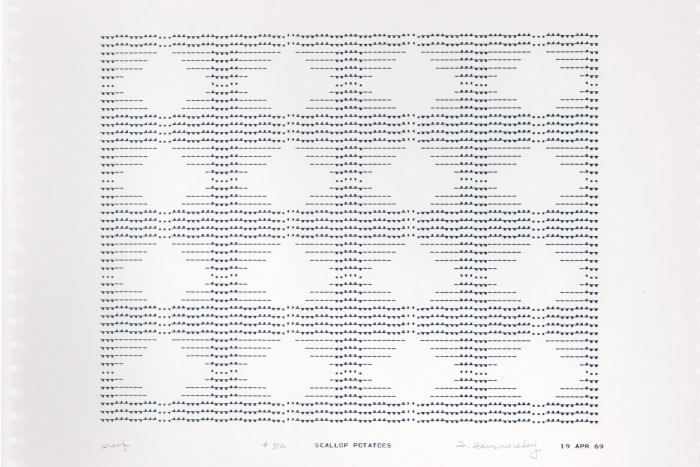

At the university he was introduced by colleagues to a software program, Art1, which enabled students and faculty to generate pictures using the university’s hulking IBM mainframe computer. Over the course of several months, he made hundreds of computer drawings — geometric abstractions composed from alphanumeric characters and symbols. They were printed on thin plotter paper with sprocket holes down each side. A year later, Hammersley concluded the series and returned to painting on canvas, going on to make some of the best work of his career.

When Leslie Jones, curator of prints and drawings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), first encountered Hammersley’s little-known computer drawings more than a decade ago, she began to research other pioneers of digital art. Jones’s exhibition Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-82 opens February 12 at Lacma and may finally usher historical digital art into the mainstream.

For decades, art made with computers was derided. Many denied it was art at all. Robert Murphy, chief executive of RCM Galerie, Paris, says that Manfred Mohr, a German artist now considered a godfather of the genre, would keep quiet about his technique for making his series of intricate plotter drawings, generated by algorithms. (Plotters, which hold pens to draw lines on paper mechanically, preceded ink-jet printers.) Once, a collector even helpfully suggested that Mohr might perhaps look into using a computer.

How times have changed. When Jones began her research, the first non-fungible token (NFT) had not even been minted and few foresaw the impact the blockchain would soon have on the traditional art world. Her interest in this field, she says, was fuelled by art-historical curiosity. “I did not do this exhibition to establish a history for NFTs, to justify all the work that’s being made now,” she says. “For me, it was really about understanding the work being made at that time.”

Coded draws revealing connections with artists from canonical movements such as Op art (Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley), Minimalism (Donald Judd), Fluxus (Alison Knowles, John Cage) and Conceptual art (Lawrence Weiner, Sol LeWitt), all of whom were influenced by the rise of computers and influential on computer art too. Coded chronicles a time largely before screens, before tradeable code-based tokens, when computers — first analogue then digital — facilitated the output of actual physical artworks, mostly on paper.

Since the crypto boom of 2021, when the first NFT to be sold at auction (Beeple’s “Everydays — The First 5000 Days”) fetched $69mn, auction houses as well as museums have dug into the origins of digital art.

In April 2022, Sotheby’s in New York presented Natively Digital 1.3, a sale that brought together contemporary NFTs with historical antecedents. In July 2022, Phillips mounted a larger online auction titled Ex-Machina: A History of Generative Art, with an informative exhibition that travelled from Paris to London, reaching as far back as the 1950s with an oscillogram photograph by Herbert W Franke, made with an early analogue computer.

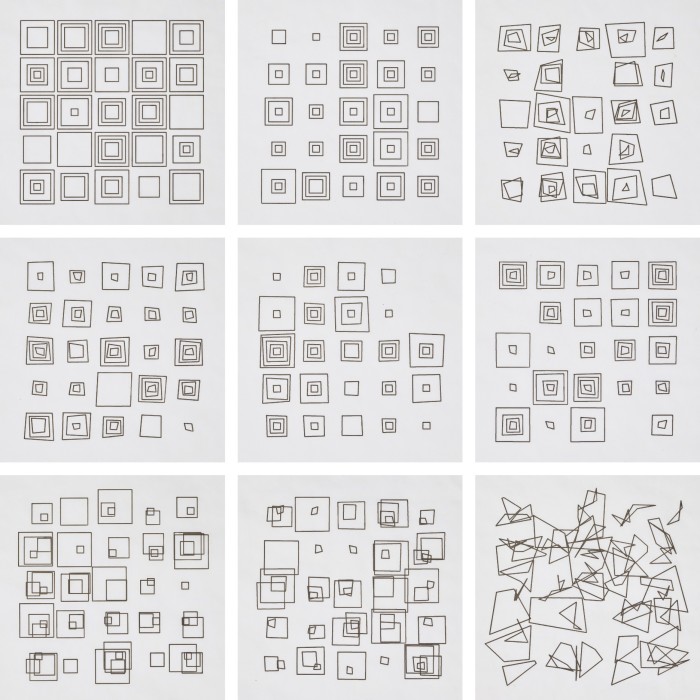

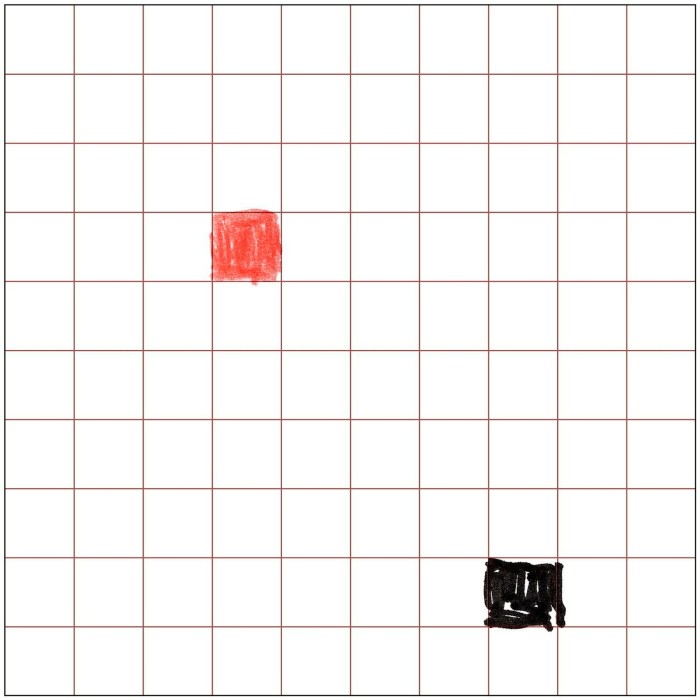

In the Phillips sale was a 1974 work by Hungarian-born artist Vera Molnár (now 99), which consisted of nine drawings on a five-metre strip of plotter paper. Around the time Hammersley was working with his university’s computer, Molnár gained access to an IBM owned by the Sorbonne in Paris. Molnár, also an abstract painter, had been working for years to “systematise” her methods. She dreamt of a machine that could generate drawings according to her pre-determined instructions. The IBM computer, which Molnár programmed with a punch card, as Hammersley had, made that machine real.

Her work at Phillips fetched £100,800, several times what her work had typically sold for in the past. That high price is something of an anomaly; the best historical computer art generally remains much more affordable, despite its rarity, than the highest priced NFTs. A new NFT by Molnár is in the Sotheby’s sale, a result of the artist’s first foray into the medium,

Such sales respond to twin impulses: the desires of digitally-native collectors to ballast their NFT collections with gravitas and historical legitimacy, and the gathering interest from traditional collectors in acknowledging the impact of digital media on virtually every aspect of contemporary culture. “The market for historic works of digital art is gaining steady momentum,” says Benjamin Kandler, project lead for digital art at Phillips in London. “It is becoming increasingly hard to find museum-grade examples in private hands.”

Wolf Lieser, founder of Berlin’s DAM Projects gallery, who has been selling and exhibiting digital art since the 1990s, describes the current interest in NFTs as “a total hype”. RCM Galerie’s Murphy agrees that the NFT market is compromised by financial speculation, while the market for first-generation digital art is led by more intellectual collectors, less concerned with prestige. “It’s not a Gucci bag, you know? Nobody’s going to go ‘Wow’ when you have it on your wall, because they won’t know what it is.”

Among the world’s leading collectors of such art are Anne and Michael Spalter. Since 1992, they have amassed more than a thousand works focusing on plotter drawings but also including NFTs and contemporary digital works such as David Hockney’s iPad drawings. Michael works in finance and is on the board of the Rhode Island School of Design; Anne is an artist and academic who wrote an early textbook on digital art. They co-curated Natively Digital 1.3 at Sotheby’s, which included one of Anne’s NFT artworks.

The ascendance of NFTs, Anne says, has helped establish the legitimacy of early digital work. “Everyone finally just accepted that digital art was art because the question had moved on to whether NFTs were art or not!”

That question seems to be settled now too. As with many museums around the world, Lacma recently acquired several NFTs by artists including John Gerrard and Tom Sachs. Thanks to Jones’s exhibition, 1960s and 1970s plotter drawings, prints and films by artists in Coded — including Molnár — have also entered the museum’s collection.

Molnár, hailed in her 10th decade as the grand-mère of computer art, has become such a household name in France that a question about her has been included in the national baccalauréat exam. Computer art has finally come home.

To July 2, lacma.org

Comments