Why business schools blend ancient and modern design

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Reverence for the past in Europe can be both a blessing and a curse for business schools in their quest to build facilities that will appeal to present and potential students.

Many European business schools are blessed with some of the continent’s most interesting yet neglected historic buildings, which can be adapted for teaching. But they are often also cursed with complex negotiations with local residents and official bodies to ensure they do not ruin the character or ambience of a structure or its location.

In southern England, the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School is raising £60m to convert the city’s first electricity plant, Osney power station, into an executive education suite. The plans, approved this year, would turn a derelict Victorian brick building on the banks of the river Thames into something reminiscent of a boutique hotel.

To get this far, however, the school had to run two informal consultations, meet-and-greet sessions with the architect, three formal public consultations, two Oxford Design Review Panels (an independent evaluation process) and six pre-application reviews with planning officers before the designs were approved.

“Executive education keeps us relevant and gives us impact,” says Sara Beck, Saïd’s chief operating officer, adding that while the process is lengthy, it is worthwhile for the presence the school gains in Oxford.

Meanwhile, on the outskirts of Paris, Insead is spending €100m expanding its original campus in the town of Fontainebleau to increase capacity by a fifth. The school has employed Jacques Herzog, the Swiss architect whose practice’s portfolio includes the Tate Modern gallery in London and Beijing’s National Stadium.

Fontainebleau has a rich history, as a home to French monarchs up to the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. This must be respected, says Peter Zemsky, Insead’s dean of innovation and the project’s sponsor. The expansion will replace some structures built in the 1960s and 1970s, not long after Insead was founded, and will halve energy consumption, he adds.

“French building codes are very demanding, so it helps that we are doing some positive things, not just trying to fit within the constraints of historic buildings,” he says. “It also helps that we are one of the major employers locally.”

Another factor is the need to maintain the local forest area, an attraction to students who live on campus. “When you build buildings nowadays, it is about two things: people and the planet,” Prof Zemsky says.

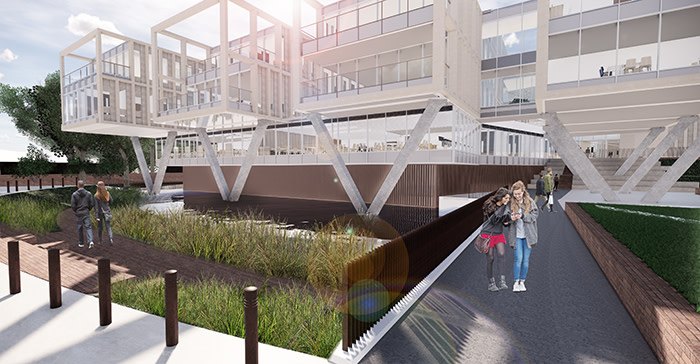

Back in England, Durham University Business School is spending £71m on a new home in the heart of the medieval city. The development is on a partly derelict plot, which includes a car park and an abandoned public bath. So far, it has required 14 months of planning and negotiation with local residents and environmental agencies to ensure the new buildings do not harm views of the city, whose castle and cathedral are a Unesco World Heritage Site.

This process has already led to a significant rethinking of the design, lowering the building by a storey and a half to ensure it sits below the tree line. Sections of the business school will stand on stilts above an artificial pond designed to reduce the impact of flooding. The pond will provide “opportunities for ecological enhancements” with the planting of insect-friendly trees and shrubs.

“The planning of a building like this takes a long time because there are so many stakeholders we need to bring in,” says Susan Hart, dean of the business school.

The amount of money available for a project makes a big difference to its ability to construct bold new campus designs. This is where US business schools often have an advantage over their European counterparts, says Nigel Dancey, senior executive partner at London-based architects Foster + Partners, whose projects include Yale University’s School of Management in the US and Aberdeen Business School in Scotland.

“American schools are better at going back to their alumni for donations, and those former students tend to give more back to their colleges,” he says.

But big construction projects can run into obstacles wherever they are. Concern about the history of a place might be a particularly European concern, but the US presents its own problems, as Insead’s Prof Zemsky discovered in the school’s project to build a small teaching facility in San Francisco. The problem here has not been planning restrictions but the challenge of getting power to the site from local utility Pacific Gas and Electric.

“California has been a more complicated environment for us to do real estate than France,” Prof Zemsky says. “A whole construction project can get bunged up if you can’t get electricity.”

Comments