Female Iranian artists offer subtle subversion

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In “Listen”, a six-channel video installation by the Iranian artist and documentary photographer Newsha Tavakolian, female vocalists appear to sing ecstatically, but their voices are inaudible — a reminder that women are not legally permitted to perform solo in public in Iran. “They’re singing their heart out, but the sound is muted,” the artist says, speaking from Tehran. For the original installation in 2010, she made cover portraits for imaginary CDs; the 8,000 cases they adorned were empty.

Tavakolian, born in 1981, grew up wanting to be a singer, but discovered photography aged 16 and became the country’s youngest photojournalist. She created “Listen” while unable to work after covering Iran’s Green Movement of 2009 for the New York Times (“It wasn’t safe to have your camera outside; you’d be arrested”), and now does international assignments for the Magnum agency. Yet, she says, “when it comes to my art, there’s no compromise.”

“Listen” is at Frieze New York with the work of other Iranian women artists represented by Dastan, a leading private gallery in Tehran whose name can mean “many hands”. Like other galleries, it shut down during the protests that followed the death last September of Mahsa Amini, who was beaten in custody for wearing the hijab “improperly”. “We haven’t had a show in Tehran since the end of last summer,” gallerist Hormoz Hematian says, but adds that openings are planned for later this month. As the Woman, Life, Freedom movement has sparked global interest in the country’s contemporary female artists, Iranians themselves are rediscovering pioneering women from pre- and post-revolutionary Iran — innovators who inspired others.

Behjat Sadr’s photographed hand appears amid thick black strokes applied with a palette knife in a “photo-painting” on view in Realism, a recent Dastan group show in London. “She was a rebel Modernist ahead of her time,” says Morad Montazami, who curated Sadr’s first UK solo show, Dusted Waters, at the Mosaic Rooms in 2018. She was “one of the first women artists in the global south to make a courageous stand for abstract and experimental practice” from the mid-1950s as an art student in Rome and Naples. Though Sadr (1924-2009) became known as the first female director of Tehran university’s visual arts department in the early 1970s, her art was not recognised by a major retrospective until the 1990s. Two of her paintings appeared in the Whitechapel Gallery’s recent show of female abstract expressionists in London.

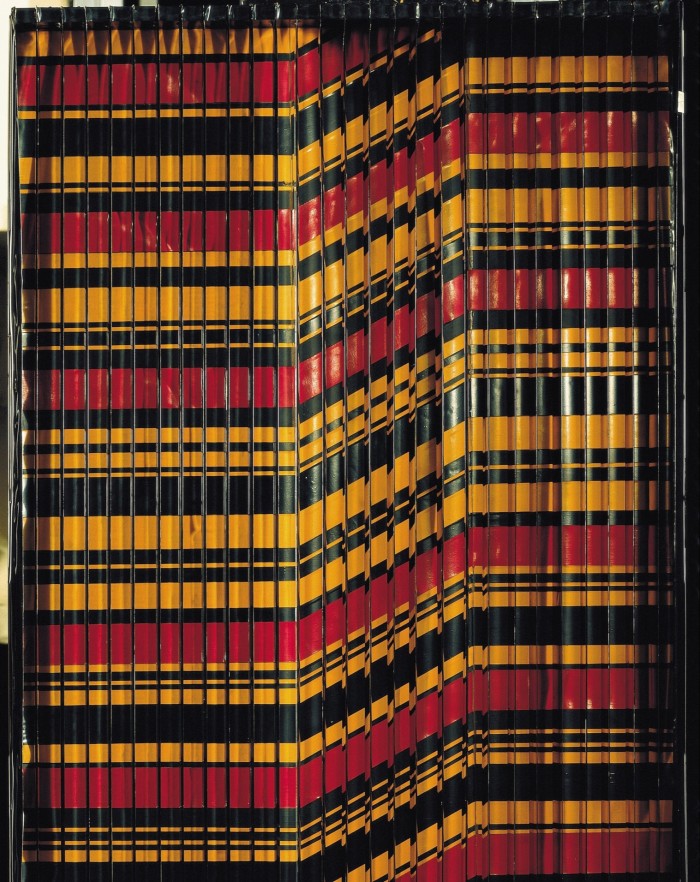

In contrast to Iran’s Saqqakhana school of art, which incorporated Persian motifs into Modern art in the 1960s, Sadr’s feverish abstraction, often inspired by nature, is more lyrical and free, as seen in an untitled oil-on-paper painting at Frieze made shortly before her death. As the artist noted in her diary, “I did not use my calligraphy or Iranian motifs in my canvas to stimulate national pride among my compatriots or the curiosity of strangers.” Among her radical experiments were Op Art reflective paintings on Venetian blinds (disparaged by one male critic as “housewife art”) and black paint on shiny aluminium.

“Black was her passion, her true impulse for more than 20 years,” Montazami says — possibly a metaphor for oil. Sadr photographed the pipelines and platforms of Iran’s oilfields in the 1970s, whose wealth enabled lavish art patronage under the shah and his empress wife, Farah — a system in which Sadr participated (taking part in the empress’s Shiraz-Persepolis Festival in 1968) but which she also reviled for its favouritism and control. The artist’s rebellious life has been as inspirational as her work, as glimpsed in Behjat Sadr: Suspended Time (2006), a documentary made by an admiring younger artist, Mitra Farahani.

Sadr left Iran for Paris soon after the revolution and died in Corsica. The other four artists on show at Frieze largely remained in Iran. Farideh Lashai (1944-2013) ranged from glass design and semi-abstract painting (a 2008 oil from the Trees series is at Frieze) to video and installations, in dialogue with works including Goya’s Disasters of War and Alice in Wonderland. Her work is “prophetic, bringing in emotion and politics”, says the artist Sam Samiee, who curated a recent retrospective in Abu Dhabi, Farideh Lashai: Afloat over Undulations. Lashai, also a bestselling novelist who translated Brecht into Persian, was jailed under the shah for having leftwing political sympathies. She tackled the complexity of Iranian history in surreal video installations such as “Rabbit in Wonderland”, in which an animated rabbit, an innocent amid geopolitical forces, encounters a map of Iran embodied in the Cheshire Cat, and meets Mohammad Mosaddegh, the prime minister ousted in 1953 in a US-sponsored coup for aspiring to take control of Iran’s own oil.

Even more indirect in its provocations is the pioneering contemporary take on Persian miniature painting of Farah Ossouli (born in 1953), who uses modern techniques, including airbrushing, to “try to pick up from where the Safavids left off”, the artist says from Tehran, referring to the golden age of court miniatures. “David and I (2)” (2014), part of her series Listen, do you hear the blowing of the darkness?, alludes to Jacques-Louis David’s oil painting from after the French Revolution, “The Intervention of the Sabine Women” (1799), in which women are mediators for peace. Systemic violence has “always been there but has changed its clothing”, she says.

The delicate decorative beauty of Ossouli’s paintings is deceptive, she says: “What you see can be the exact opposite of reality.” In the margins and illuminations, she adds batons, riot police, planes and bombs. “They look like traditional ornaments — until you look closely.” Her interest is partly in “how governments glorify war; how they present something so dark as if it were beautiful”.

There are also layered meanings in the suspended yarn sculptures of women by Bita Fayyazi (born in 1962), though “all my works are collaborative,” she says. Partly inspired by Louise Bourgeois, Fayyazi moved from ceramics to installations, using yarn and plaster. Fayyazi’s first model was her grandmother at 80: “I was so drawn to her physical presence, her fleshy, voluptuous body, and asked her to pose for me nude — which she did with such pleasure for my camera. The women I’m still making are her body,” she says. Fayyazi exhibits abroad but is unable to show such works publicly in Iran, given that exhibiting nudes is prohibited. In art as in daily existence, “we have a parallel life — interior and exterior,” she says.

For Tavakolian, “All women artists who work here and did in the past are a piece of a big puzzle. Together, we complete each other.”

Comments