BlackRock’s active strategies threaten to steal the show

Simply sign up to the Fund management myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

BlackRock’s stockpickers are accustomed to toiling in the shadow of the group’s exchange traded fund business, which last year sucked in more than $1bn a day on average from investors.

But as its index-tracking business drove BlackRock’s assets past the $10tn mark for the first time last quarter, there are signs that its actively managed investment strategies are finally starting to fire at the world’s largest money manager.

The businesses, which include equity mutual funds, traditional bond funds, esoteric private credit vehicles and hedge funds, accounted for 60 per cent of BlackRock’s fee growth in the final three months of 2021. That is in sharp contrast to just a few years ago when the company’s $3.3tn iShares ETF unit alone generated three-quarters of it.

BlackRock executives say that a multiyear effort to invigorate its actively managed equity funds business, and to build up a panoply of so-called alternative strategies to complement its active bond funds, is now bearing fruit.

“Active is probably our biggest success story,” Gary Shedlin, BlackRock’s chief financial officer, told the Financial Times. “We’ve always been a very strong, active fixed-income manager but, frankly, active equities and alternatives have not been huge drivers of our success until more recently.”

The renaissance of its actively managed strategies is a departure for a company that over the past decade has become synonymous with passive investing, whose seemingly irresistible rise has driven fees ever lower across the asset management industry. Alongside $3.3tn in iShares, BlackRock’s passive business includes $3.1tn in index-tracking mandates from pension plans, sovereign wealth funds and insurers.

The company has $2.6tn in its array of actively managed strategies, but the performance of its equity funds has long been troubled, leading to cumulative outflows of almost $30bn in the decade that ended in 2020, according to Morningstar data.

Yet BlackRock started out as a niche, active bond house founded by a group of First Boston and Shearson Lehman fixed-income traders and analysts led by chief executive Larry Fink. A series of acquisitions, most notably of Merrill Lynch Investment Managers in 2006 and Barclays Global Investors in 2009, transformed it into the industry’s biggest and broadest investment group.

After nearly uninterrupted outflows since 2014, BlackRock’s active equity funds have now enjoyed seven quarters of net inflows, according to Morningstar. Coupled with its traditional bond funds and alternative strategies, its active business took in more than $100bn in the last three months of 2021, propelling the year’s total to $267bn.

“It’s been a long journey,” Fink said in an interview. “So much of our notoriety might be because of ETFs and indexed investing, but the reality is that we’ve always been a very large active manager.”

Michael Cyprys, an analyst at Morgan Stanley, noted that although still dwarfed by passive funds, the comeback for its active strategies was having a meaningful impact on BlackRock’s revenues, because of the fatter fees they command.

“Active is firing on all cylinders,” he said. “BlackRock is frankly demonstrating that they’re also a powerhouse for active management, which is maybe catching some people by surprise.”

Revenues at its active equities business grew 48 per cent last year to $2.57bn, while the group’s active fixed-income strategies notched a 12 per cent increase to $2.2bn. Revenues at its alternative investment business, encompassing hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, infrastructure, real estate and private debt, jumped 21 per cent to $1.5bn.

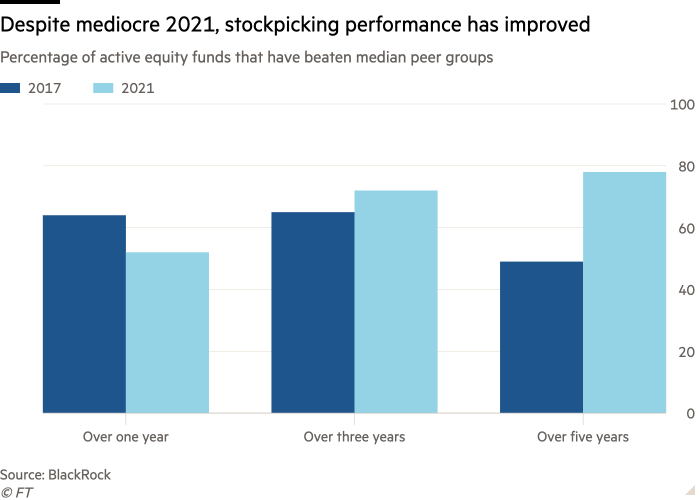

The performance of BlackRock’s stockpickers actually faded slightly in 2021, when only 52 per cent beat what the group considers their peer median, down from 78 per cent in 2020. However, over the past five years, 78 per cent have outperformed, according to BlackRock’s estimates, up from a record of just 49 per cent in the five years to early 2017.

Across the industry, internally generated performance data versus other active funds tend to flatter an asset manager’s results, but Fink said the improved performance indicated how “Project Monarch” — a restructuring of the active equities division launched in 2017 and designed to infuse it with the data nous of BlackRock’s quantitative unit — is paying off.

“There’s no question that after Project Monarch our investment performance improved, but we also built out our distribution platform and the flows have been driven by winning entire holistic mandates,” Fink said, referring to coups like taking over management of British Airways’ £21.5bn of pension plans in 2021.

Although BlackRock’s top brass is quick to credit the internal overhaul, it remains unclear whether the asset manager is merely benefiting from an industry-wide rush of money into active investing strategies.

Last year was the best one for active equity mutual fund inflows since at least 2000, according to EPFR. It is a picture few believe will last.

BlackRock’s active funds will also be heavily tested in the coming years as central banks are expected to ratchet interest rates higher to combat inflation. History also cautions against a sustained revival — the vast majority of active funds have underperformed their primary benchmarks over the past decade.

At the same time, the downward pressure on the fees that active funds can charge shows no sign of easing, largely because of competition from cheap index-tracking funds such as the ones BlackRock sells.

BlackRock’s own Equity Dividend Fund, with $21.6bn of assets under management, charges 0.71 per cent a year but has underperformed its benchmark over the past decade. The company also sells a comparable ETF, which now manages nearly $57bn, with a 0.19 per cent annual fee.

Morgan Stanley predicts that after contracting 3 per cent last year, industry-wide fees will shrink by another 2 per cent in 2022, extending an uninterrupted slide spanning more than two decades.

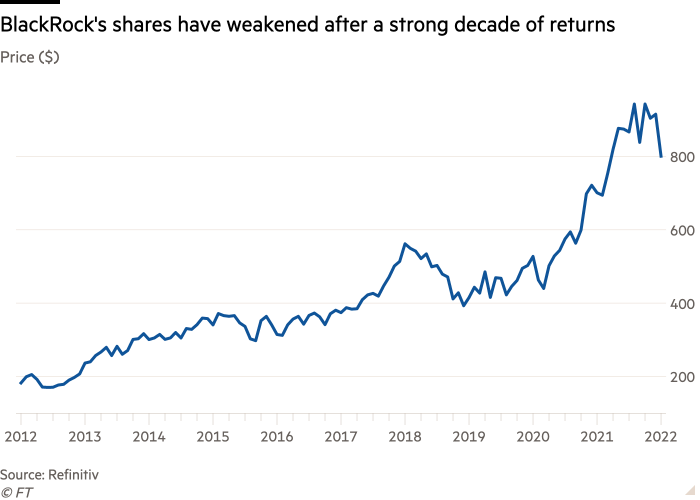

Firmer signs of improvement in its actively managed strategies have done little for BlackRock’s share price this year, which is down 12 per cent as markets have started on the back foot. Investors were also unnerved when BlackRock signalled at its results earlier this month that it would ramp up spending.

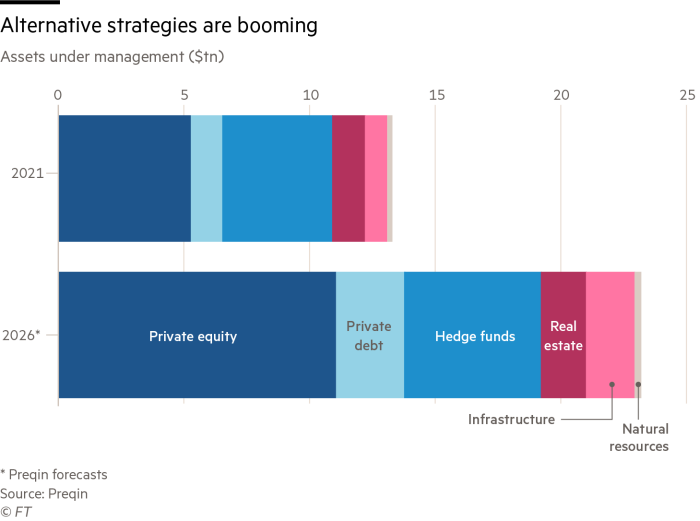

Executives at the company are betting that its growing alternative investment unit will benefit from the industry’s “barbelling” into mostly cheap passive funds on one hand and pricier private investment vehicles on the other — and help counter any weakness in more traditional areas such as stockpicking.

Alternative investments swelled to $13.3tn last year, according to data provider Preqin, as investors sought out higher returns. Preqin predicts that the sector’s assets will grow to $23.2tn by the end of 2026.

BlackRock’s own alternative investment business has seen inflows explode from less than $5bn five years ago, to $25bn in 2020 and $42bn last year, notes Fink.

“This is no longer a cottage industry,” said Edwin Conway, global head of BlackRock Alternative Investors. “This is far from a fad. It’s a structural shift, not a cyclical one.”

Nonetheless, BlackRock may again simply be riding a broad boom in “private capital” as investors, desperate to escape the dimming outlook for mainstream markets, throw money at the sector. Competing with the established giants of the alternative investment business is expected to be difficult, even for a company of BlackRock’s size.

Tellingly, the stock market value of Blackstone — the alternative investment behemoth that BlackRock was spun out of in 1994 — last year surpassed the asset manager’s for the first time since 2007.

Morgan Stanley’s Cyprys argues that BlackRock’s heft, coupled with some smaller acquisitions, means that it should do well in private capital too, but noted that the biggest part of the sector would be tricky to crack.

“The most challenging part is the flashier private equity part of the industry,” he said. “You struggle to see success stories of public market managers doing well in the private equity arena.”

Comments