Gig economy: the best live music venues in Melbourne

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is part of a new guide to Melbourne from FT Globetrotter

Melbourne declared itself the live music capital of the world last decade after it crunched the numbers and found that it had overtaken Austin, Texas, as the best place to see a show. According to a census conducted by a music-trade body, the city had one live music venue for every 9,500 residents, which compares to about 18,500 in New York and 34,000 in London.

Melbourne is known to be a sports-mad town, given the popularity of Aussie Rules football, rugby, cricket and basketball and international events such as the Australian Open tennis and the Grand Prix. Yet by 2017, when the census was conducted, more than twice as many people attended gigs and concerts here every year.

Discounting the egregious caterwauling of soap stars, Melbourne has punched above its weight in producing artists from a wide variety of genres. Pioneering composer Percy Grainger, concert pianist David Helfgott from the Oscar-winning movie Shine and Olivia Newton-John are some of its most famous exports, while Dame Nellie Melba took her stage name from her hometown.

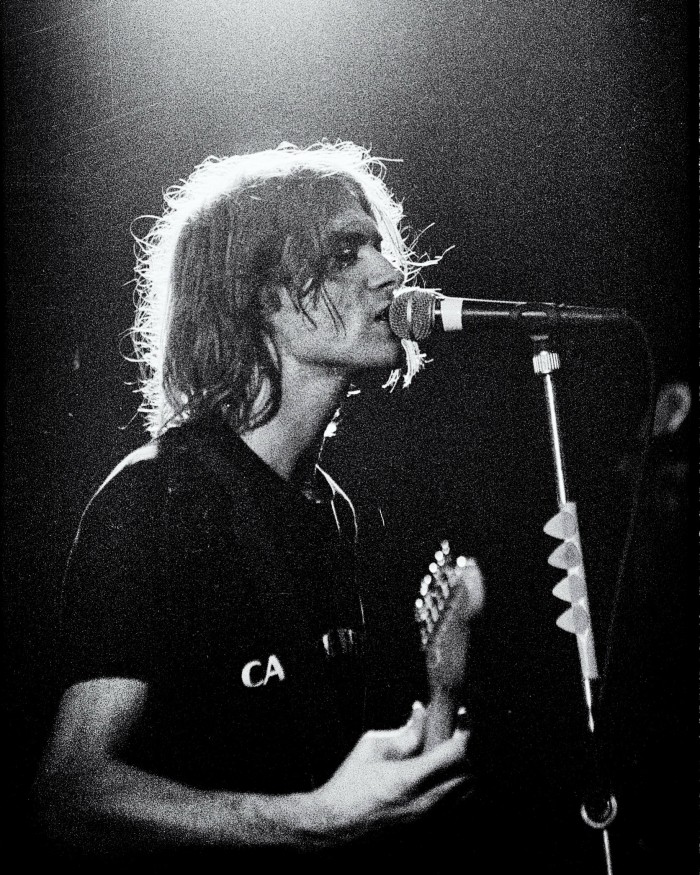

Acts including Men At Work, Crowded House (who formed in the city), The Birthday Party and its singer Nick Cave, the sublime Dirty Three and the legendary punks Cosmic Psychos emerged in the 1980s and ’90s to take Melbourne’s sound around the world. A new generation led by King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard and Amyl and the Sniffers has carried that flame further in recent years. All of them have played in some dingy Melbourne venue at some point in their journey.

The roots of Melbourne’s vibrant music scene can be traced to the Sunbury Pop Festival held to the west of the city in the early 1970s. It was intended to be Australia’s equivalent of Woodstock but instead it birthed the country’s emerging pub rock scene and showed Australians, who had long suffered from “cultural cringe”, that homegrown acts could hold their own against international headliners who rarely toured the faraway country.

Within years, the suburban pubs of Melbourne were raging and by the 1980s, the city had earned a reputation as having the best live alternative-music scene in the world, which had come to the attention of rival cities as distant as Seattle.

That homegrown rough-edged music, which didn’t take itself too seriously, found a natural ally with US alternative bands such as Mudhoney, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion and Nirvana, who started touring the country in the 1990s. A member of Fugazi, the righteous punks who led the way in touring Australia, was even beaten up by a rogue kangaroo when camping in the bush as Australia’s thriving live-music sector came to the attention of the world.

Fast forward 30 years and live music in Melbourne has ridden out one of the longest Covid-19 lockdowns in the world to turn it up to 11 again. It is a source of pride for many Melburnians that the evocative graffiti-strewn AC/DC Lane — an inner city laneway featuring tributary murals of the band’s deceased members Bon Scott and Malcolm Young, as well as other musical acts — is located in their town and not in Sydney, where the band originally formed.

Here is my guide for the best places to see and hear great music in a city that has long acted as a hub for the finest musicians and bands from around the country, no matter what genre.

Pick up a copy of Beat — the longstanding music magazine and gig guide — when you visit Melbourne for concert information.

Sticky-carpet venues: rock, metal, electronic, experimental

Good for: Random bands (often interminably random). Moshing. Beer

Not so good for: Tinnitus. BO

FYI: Booking is necessary for some of the larger venues, but most places are walk-in with cheap cover charge. Most venues are in a small outer radius from the centre of town, accessible via tram or taxi

It is in Melbourne’s inner fringes, not its centre, where the good, the bad and the ugly bands will emerge. Northcote, St Kilda and Brunswick have grown into vibrant live-music destinations as the traditional inner-city working-class entertainment strongholds have gentrified.

A longstanding favourite for those in the market for artists that feel like a figment of your imagination the next morning is The Tote Hotel (67-71 Johnston Street) in Collingwood, which has been hosting up-and-coming acts for 40 years. Anyone who is anyone in the Australian scene has played on one of its stages. It even has a resident ghost.

The Tote was almost lost to time in 2010 when licensing laws changed and it nearly closed down. A public campaign to save it brought it back from the brink. That means that you can still wander in and for a few dollars see bands and artists with exotic names like Smug Anime Face, Null Hypothesis and Bacchus Harsh that may — or may not — go on to great things. Every few years it feels like a new generation has claimed The Tote as their own, meaning the crowd can seem quite youthful.

The venue advertises itself as “cheap and loud” — a very accurate description. The ceilings are cracked and the floor of the smaller upstairs stage feels a little too bouncy at times, which, paired with dystopian techno or punchy heavy metal, can give the punter an “end of days” feeling. The Tote has just been put on the market but will continue as a music venue if a sale completes. Whether the new owners maintain the down-at-heel vibe remains to be seen but they’d be foolish to tamper with a winning formula.

The Espy on The Esplanade in St Kilda is another institution that has survived by the skin of its teeth against the constant march of property development. Its Gershwin Room has been used for many a live album, with hellraisers The Chats one of the latest to put their name above the door. The unwieldy venue, which can be chock-full of alpha males and backpackers on occasion, is now indirectly owned by private equity company KKR, which perhaps undermines its street cred a little. The nearby George Lane off Fitzroy Street has carved out a local reputation for Americana and rock ’n’ roll shows in recent years and is an alternative bet for a good evening.

Those in the hunt for bigger bands and upcoming international acts not ready for the stadiums should head to the Corner Hotel (57 Swan Street) in Richmond, which has played a part in the personal history of most Melburnian music diehards. In my youth, I slept on the park benches of Richmond waiting for the 5am train back home on a few occasions to see top live acts such as You Am I and The Tea Party. I also suffered my own version of Stendhal Syndrome when I face-planted during a particularly hypnotic show by The Necks. The venue is known for being hot and uncomfortable during the summer, and you can get stranded behind one of its giant columns during a sold-out show.

If you fancy a spontaneous gig crawl without overthinking the need to book in advance, then head to Northcote. You can start at Northcote Social Club (301 High Street) — a smaller venue than The Corner that attracts mid-level touring bands and has a great sound system and a decent beer garden — and flit up and down the high street heading towards Thornbury between the dozen or so small venues that have popped up in recent years. Bar 303’s (303 High Street) back room offers a particularly appropriate end to a late night. I was aurally assaulted by a fantastic stenchcore band the last time I was there. Few other cities could offer such cultural delights.

Hamer Hall

100 St Kilda Road, Southbank VIC 3004

Good for: Acoustic quality, Brutalist architecture, one-stop shop for culture

Not so good for: Latecomers

FYI: Booking essential for major touring acts, opera and orchestras. Head to bars and restaurants such as Bluetrain next door along the Southbank for pre- and post-show

There are few more recognisable concert halls in the world than the Sydney Opera House. That is not lost on Melbourne, which has a fierce rivalry with its northern counterpart and believes it still has an acoustic edge over a building that Clive James referred to as a “portable typewriter full of oyster shells”.

When I worked as an usher at Hamer Hall — Melbourne’s equivalent of the Opera House — the quip was that music fans went to Sydney to be seen outside the city’s concert hall but they came to Melbourne for the sound inside the venue . . . and they went to Adelaide for the ample parking.

Hamer Hall, which seats 2,500, is part of Arts Centre Melbourne on the Southbank of the Yarra river, which includes a nearby red velvet and gold metal complex containing three theatres, as well as the fantastic Australian Music Vault permanent exhibition that includes the history of the city’s live music scene. These all sit under a 162m white and yellow spire that acts as a beacon for the performing arts in the centre of Melbourne.

The concert hall is a 30-second walk away on the river and appears less glamorous in style. Opened in 1982, the rounded concrete edifice was designed by architect Roy Grounds in a distinctive Brutalist style that is remarkable for a city prone to throwing up artless glass office blocks and ill-thought out shopping arcades on every street corner.

From some angles, the hall looks like a giant pillbox with its slit-like windows and rounded concrete exterior. Inside, the soft padded walls are lined with reindeer leather and give the impression of an asylum.

The pay off is the imposing auditorium — described as having a “cyclopean character” by Architecture Australia — which was built to match the ambitions of the city’s orchestras. Sitting in the front of the balcony was once akin to peering down from the lip of a volcano.

Work has been done to remove any elements that deadened the sound in the cave-like space, including a move to replace the old beige comfy seats with timber-backed models that reflect rather than absorb sound.

Hamer Hall is home to the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and the preferred venue of the city’s chamber orchestra. It also doubles up as one of the city’s key large venues for touring artists and performers, as well as the international comedy festival (which this year runs from March 29 to April 23).

Hamer Hall, or the Melbourne Concert Hall as it was then called, proved to be a key part of my life when I worked the doors as a university student in the 1990s. I learnt the ropes by confiscating ice creams off well-heeled “patrons” and ushering agitated latecomers into hidden rooms so they could watch the shows without disturbing those on time. It was also where I met my wife.

It was here I was first exposed to Dvorak, Stockhausen and Verdi and the Australian version of Last Night of the Proms. I saw Billy Connolly six times in a row on one of his Australian tours, and it was the location of the first of about 30 Elvis Costello concerts that I’ve since attended. I snuck into that show by putting on my usher’s uniform and pretending that I was on duty, hiding in plain sight.

Jazz clubs

Good for: Ambience, quality of musicians

Not so good for: Oneupmanship between the venues

FYI: Melbourne has a healthy scene all year around, but it really lights up in October when the international jazz festival hits

The Bennetts Lane Jazz Club, located on an inner-city dead-end street with the same name as the venue, was a hallmark of Melbourne’s jazz scene for years. It acted as both a home for local jazz musicians and a haven for touring artists, many of whom appeared at the city’s jazz festival, meaning that the tiny venue played host to the likes of Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Wynton Marsalis.

However, it was a non-jazz artist who enshrined the popular venue into Melbourne folklore. Prince played at Bennetts Lane not once but twice during tours of Australia. The second show was a spontaneous three-hour solo set in front of about 70 people that kicked off at 2am.

Bennetts Lane — once dubbed the best jazz venue in the world by Lonely Planet — closed in 2017 after its founder Michael Tortoni, a jazz bassist and former stockbroker, succumbed to pressure from developers to sell the site. There was genuine concern that Melbourne’s jazz scene was in peril. That has proved to be well wide of the mark.

Tortoni moved a few miles across town to Brunswick in the north of the city and set up The JazzLab (27 Leslie Street), once again down an assuming narrow side street now lit up with the venue’s neon sign. The classy-looking oblong room — once a furniture warehouse — is based on the original Bennetts Lane set-up.

About 200 can fit into the space comfortably and while it hasn’t quite captured the mood of the original venue, it is a great hangout. As Tortoni explains, more musicians now reside in Brunswick — a former industrial area that has fallen to the hipsters — than anywhere else in the country, so The JazzLab may have situated itself perfectly for the next wave of Melbourne jazz.

Other options include The Night Cat (137-141 Johnston Street) in Fitzroy, which puts on the likes of Ethiopian legend Mulatu Astatke. The nearby Uptown Jazz Café (177 Brunswick Street) is a thriving smaller venue in what used to be a rock-heavy stretch connecting Melbourne to the eastern suburbs. It takes its name from Melbourne’s first jazz club, which was established by Graeme Bell, godfather of the local scene, in the 1940s.

Yet all is not lost back in the centre of town either. The Paris Cat Jazz Club (6 Goldie Place) has reinvigorated the Central Business District jazz scene since it opened in 2005, while the nearby Bird’s Basement (11 Singers Lane) boasts of having the best acoustics for a jazz venue in town. It doubles as a restaurant in the vein of London’s Jazz Café and floor space is prioritised for diners, so booking in advance is advised.

For international visitors put off by a small trek into the fringes of Melbourne, those central venues present a convenient alternative.

Share your favourite Melbourne music destinations in the comments

Follow FT Globetrotter on Instagram at @FTGlobetrotter

Comments