Antony Gormley: ‘Architecture is our second body’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Sir Antony Gormley met a 21-year-old art dealer named Xavier Hufkens at his Eric Parry-envisaged London studio in 1986, he could not have anticipated a 35-year friendship and collaboration. “He was wearing a yellow jacket and looked put-together,” the British sculptor recalls of the art dealer in the making.

Today, the two are chatting over tea and coffee at Gormley’s David Chipperfield-designed studio at King’s Cross. Their banter is harmonious and the two fill the gaps in their recollections of that first encounter: Gormley remembers a big storm had destroyed his studio windows and Hufkens, then a young law-school dropout, was keen to converse about Gormley’s 1984 show at New York’s Salvatore Ala Gallery.

“When you’re that young, you are a little pompous, you have no fear,” says Hufkens, now 57, who offered the young Gormley, who by then had already exhibited at the Venice Biennale and the Serpentine Gallery, an exhibition at the gallery he was planning to open in an industrial building on Rue de l’Église in Brussels.

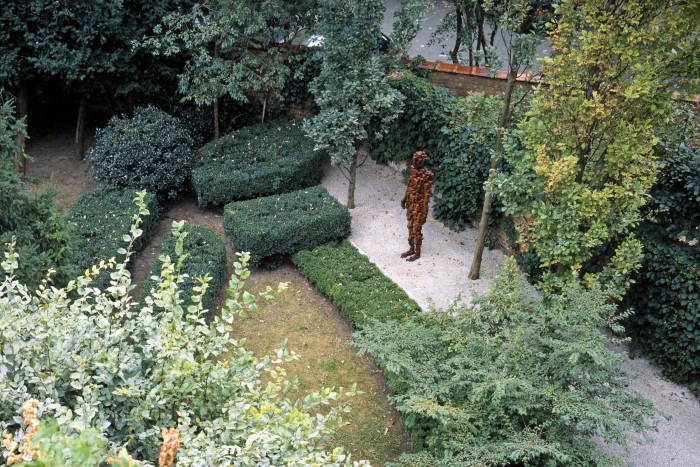

Gormley agreed, and the show of plaster, fibreglass, lead human figures and abstract forms inaugurated the two-floor gallery in April 1987, launching the career of Hufkens, who is now one of Europe’s most influential gallerists, while expanding the artist’s presence in Belgium. Many more shows and dinners at Au Vieux Saint Martin later, Gormley has recently opened Body Field, his ninth show with Xavier Hufkens at the gallery’s brand new Robbrecht & Daem Architects-designed space on Rue Saint-Georges in Brussels. The minimalist concrete building opened in June.

Hufkens’s gallery career enjoys a certain circularity. He says Gormley – whose most recognised work includes the Angel of the North and the solitary figures of the public-art installation Event Horizon, first installed on rooftops around London in 2007 – was partly the impetus for building the new contemporary space, which triples the square footage previously available for exhibitions. “When you have an artist you’ve already staged eight shows with, you need a space for new experiences,” he says.

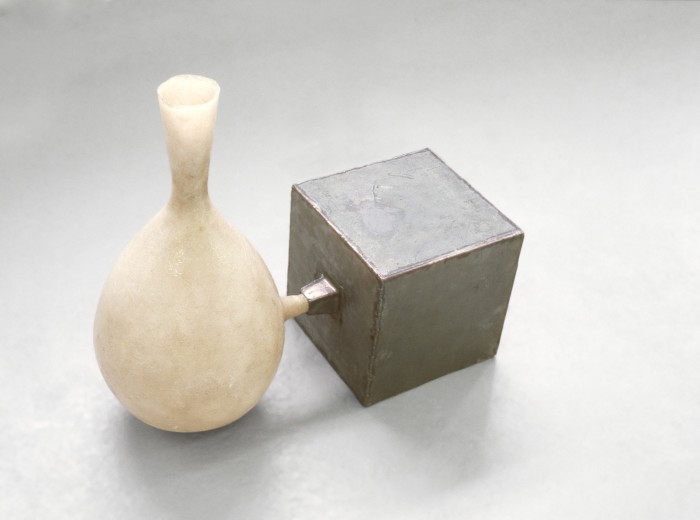

Gormley’s artistic response befits his friend’s gesture. Body Field includes a 155m-long, site-specific steel tube installation entitled RUN III (2022), which occupies the ground floor of the six-storey 827sq m gallery, leading the viewer through an orchestration of new body-inspired geometric cast-iron and concrete sculptures. Another eye-catching piece, CORNER (2022), consists of a concrete sculpture replicating the artist’s own body – in this case crouched but reduced to minimalist geometric silhouettes.

While Gormley’s own likeness has long been his main source, the pandemic has ignited a further desire to “meditate on our vulnerability and fear of claustrophobia”. As such, the artist calls the two works “bunker sculptures”, while rather more corporeal-looking works are peppered throughout the 27m-high gallery. “The body is where we dwell – it’s the closest bit of the material world to us,” he says.

The harmony between bodies and architecture is at the core of Gormley’s human forms. “Architecture is our second body,” the 72-year-old artist says. “As our species becomes more urbanised, we depend on the two grids: our internet connections and the city’s physical grids marked by organised architecture.”

Gormley has watched closely as Hufkens has transformed his gallery of three decades, a bold and risky move for an established venture. “Stripping down what was there and replacing it with a modernist – almost brutalist – building within a row of bourgeois townhouses was totally astonishing,” Gormley says. “Architecture of this ambition tests our ideas about habitat.” He considers the building to be a manifesto for the idea that “art can’t simply decorate what already exists but rather has to confront it”, and calls the new space “a rite of passage for all its artists”. Xavier Hufkens’s roster includes everyone from Tracey Emin and Lynda Benglis to Paul McCarthy and Roni Horn. He also supports emerging talent and has taken an interest in the careers of artists such as Nicolas Party in tandem with representing the estates of Robert Mapplethorpe, Louise Bourgeois and Richard Artschwager.

Gormley’s insight into how this new artists’ home would unfold through renderings has allowed him to develop his own visual lexicon. When he finally saw the building in person in September, he was stunned by “the authority of the flow across the floors and the indirect light sources seeping in from unusual places like a skull”.

The pair’s friendship remains steadfast. Whether dining together in London or Brussels, Gormley allows Hufkens to choose the restaurant – and order the food, “because he always knows what is good to eat where”. They recently roamed the streets of the Belgian capital after dinner to imagine where they could place one of Gormley’s massive public sculptures. It is not the first time: the biggest public-art project they worked on together was Exposure, which sits on the tip of a lowland in Lelystad in the Netherlands. The 60-tonne, 25m figure has been crouched in the remote Dutch town since 2010, although the dealer, who helped fund the project with Gormley partly through the sales of the sculpture’s limited-edition maquettes, has not visited the site since its unveiling.

Although the friends have had discussions about placing one of Gormley’s public works in Brussels, the lead figure from the artist’s first exhibition will remain in the gallery. Sadly, the wooden plank on which the sculpture originally stood back in 1987 has now gone missing. “I think I can find another plank,” the artist laughs. What remains is the enduring bond between artist and dealer, a rare thing within the art world’s constantly shuffling dynamics. “The reason why I have a gallery has always been to be surrounded by artists,” Hufkens says. “As a young man, I always felt a bit on the edge of the world, and my conversations with artists have been the only way to have an eye on life.”

Similarly, Gormley says their camaraderie has relied “on a mutual excitement about testing out what is possible”. He concludes: “This also includes risking to destroy the inhabited to build something at another level of concentration.” Time will tell if this new space elevates the experience of visitors.

Antony Gormley at Hufkens Gallery: a timeline of exhibitions

2002: Antony Gormley

2006: You and Nothing

2009: Aperture

2013: According to a Given Mean

2017: Living Room

Body Field is at Xavier Hufkens, 6 Rue Saint-Georges, 1050 Brussels, Belgium, until 17 December

Comments