Researchers hunt for new dementia detection methods

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Diagnosis plays a key role in the battle against dementia. Although the world still lacks a proven treatment for Alzheimer’s or, indeed, any form of dementia, many people who may be developing symptoms — and their families — appreciate knowing the likely course of the disease, for planning and other purposes.

At the same time, scientists developing dementia drugs need a reliable diagnosis, preferably before the onset of symptoms, to identify participants best suited for their clinical trials.

“Globally, dementia is grossly underdiagnosed,” says the World Dementia Council. In the UK, where the National Health Service has made dementia diagnosis a priority, around 67 per cent of the estimated number of people with the disease have received a diagnosis — one of the highest rates in the world.

According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, only 25 to 50 per cent of dementia cases are recognised and documented in many other high-income countries, and the rate is much lower in poorer ones. “Approximately three-quarters of people with dementia [worldwide] have not received a diagnosis,” ADI estimates.

Fiona Carragher, chief policy and research officer for the Alzheimer’s Society in the UK, gives two main reasons for the under-diagnosis. “The brain is the most complex organ in the human body and dementia is a complex set of diseases, so it is not surprising that we don’t have a simple test for the earlier stages,” she says. “Linked to that is the gap in research funding in dementia, including diagnosis, compared to other diseases over the past 20 to 30 years.”

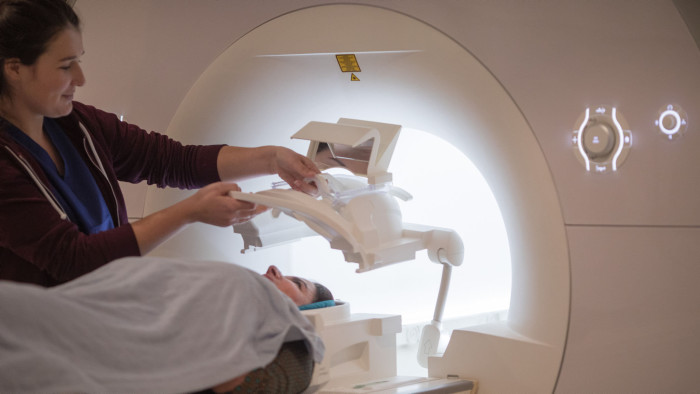

Although research into new techniques — including blood tests, brain scans and electronic methods such as virtual reality and speech-pattern matching — is gathering pace, most clinical diagnosis today relies on traditional methods such as cognitive and memory tests combined with interviews with patients and their families. These may be supplemented with additional tests to help identify the type of dementia.

Scans for example can show the shape of the brain and its biochemical activity. Another option is a lumbar puncture to take a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid from the lower back and measure levels of proteins characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

Many researchers are looking for biomarkers — molecules characteristic of a particular form of dementia — in blood. This is challenging, because the blood-brain barrier prevents much leakage from the brain into the bloodstream but the increasing sensitivity of biochemical tests is making biomarkers easier to detect.

Researchers at Washington University in St Louis last month reported they could identify people with brain changes characteristic of early Alzheimer’s with 94 per cent accuracy. They used mass spectrometry to measure the level of amyloid beta protein in blood — and combined this with each subject’s age and genetic analysis.

“While the idea of an Alzheimer’s blood test feels like it has been around for decades, advances in technology over the last couple of years mean that it is now becoming a reality, and fast,” says Dr James Pickett, Alzheimer’s Society head of research. “But it’s important to note this isn’t a blood test for dementia — it tells us that amyloid deposits are in the brain, which are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, but they are also found in healthy older people too.”

Brain scans are another fertile field for diagnostics research. Last month Oxford university launched Oxford Brain Diagnostics, a spinout using new computer algorithms to analyse MRI scans of the cerebral cortex for changes characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Adding to the diagnostic challenge is growing evidence of the sheer complexity of neurological conditions that can lead to dementia — and the difficulty of distinguishing between them.

An international research team recently published evidence in the journal Brain for a new type of disease that produces dementia symptoms very similar to those of Alzheimer’s, which they call late limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy or LATE. Unlike Alzheimer’s, in which two toxic proteins, tau and amyloid beta, accumulate in the brain, LATE is caused by another protein, TDP-43, which is usually present in the centre of nerve cells but may change form and spread out into the cell body as people get older.

Kirsty McAleese, a neuropathologist studying postmortem brain tissue from dementia patients at Newcastle University, highlights the complexity. “More than half of people with Alzheimer’s also have some signs of additional pathology in their brain, which may be LATE or dementia with Lewy bodies [abnormal groups of protein] or vascular dementia,” she says. “About 20 to 25 per cent have ‘mixed dementia’ with at least two full-blown pathologies.”

Ms Carragher sees a future combining a variety of techniques for each patient. These might include brain scans, blood tests and genetics but also analysis of the way the individual talks, walks and performs on special tests.

“With AI we’ll be able to bring all the diagnostic data together to provide everyone with a personalised approach,” she says.

Comments