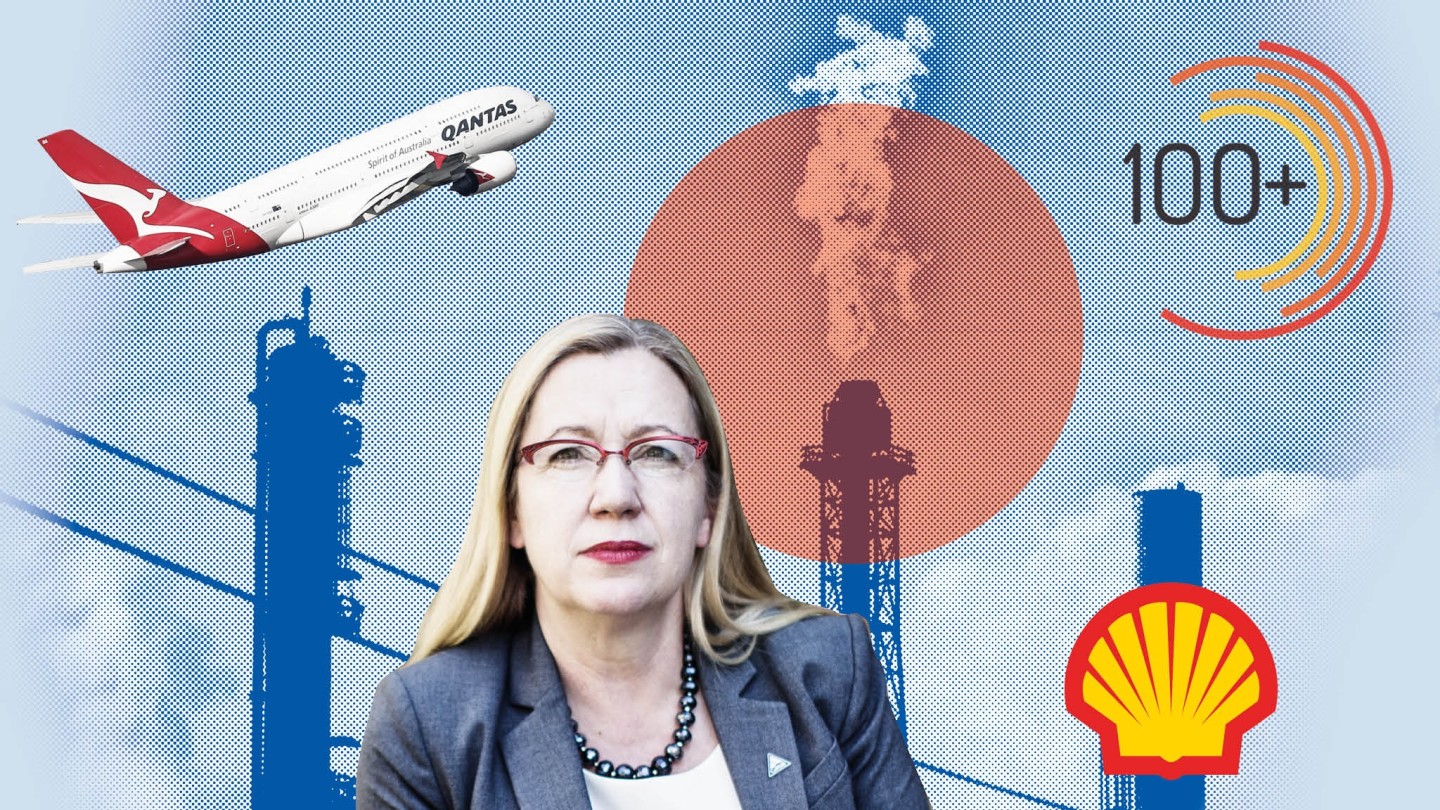

Corporate eco-warriors driving change from Shell to Qantas

Simply sign up to the ESG investing myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Ben van Beurden announced in 2018 that Royal Dutch Shell would set short-term targets to cut its carbon footprint, it marked a rapid U-turn by the oil chief executive and a big win for a group of investors.

Just months earlier, Mr van Beurden had argued that setting hard targets to reduce carbon emissions was a “superfluous experience”. But after concerted pressure from the Church of England pension board and Robeco, the Dutch asset manager, which had lobbied the oil major on behalf of an investor group called Climate Action 100+, Mr van Beurden relented.

In the first pledge of its kind in the sector, Shell said it would set carbon reduction targets and link these to executive pay. Since then companies from airline Qantas to energy group Repsol have set goals to drastically cut their emissions. Such reductions often came after tough conversations with investors from the influential CA 100+ group, which was formed in December 2017 with a five-year plan to drive change at the world’s biggest carbon emitters.

Fiona Reynolds, managing director at Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), one of the organisations behind CA100+, says its achievements in such a short space of time are notable. “It is the largest investor-to-company initiative in history. It is really driving the conversation on climate.”

Halfway through its five-year timeline, CA100+ now has more than 450 investor members with $40tn in assets. Industry heavyweight BlackRock joined earlier this year.

To its advocates, CA100+ has been revolutionary, collating hundreds of disparate investors behind a single cause and driving change at companies from PetroChina to BP. It has become the flagship group through which the investment industry demands global corporations act on climate change.

Its critics, however, argue the group lacks transparency, is unwieldy, not tough enough and used by companies as a smoke screen for bad behaviour.

“We all need Climate Action 100+ to succeed,” says Dan Gocher, director of climate and environment at the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, a shareholder advocacy organisation. “But the problem at the moment is there is a lack of transparency, there is a lack of milestones. What are they measuring themselves against?”

The new climate warriors

For years, eco-warriors, non-profit organisations and small investors have been the driving force behind campaigns to convince big companies to take climate change seriously. They protested outside business headquarters, filed shareholder resolutions and spoke out at annual meetings. Large investors, in contrast, largely remained silent — at least in public.

But in the wake of the Paris agreement, a rising number of large investors have become alive to the investment risks of global warming.

CA100+ also traces its roots back to the Paris climate talks in late 2015.

In the run-up to those talks, Anne Simpson and the team at Calpers examined the US public pension fund’s 10,000 public equity holdings and found that fewer than 100 were responsible for the vast bulk of emissions. It was a lightbulb moment for Ms Simpson, who had initially felt overwhelmed at the idea of conversations about climate with 10,000 companies.

“We realised we didn’t have to boil the ocean: we needed to focus on those 80 companies. The second thought was if it is true for Calpers [that only a small percentage accounted for most emissions], it is probably true for other asset owners.”

The following year, over a series of breakfasts at the French mission to the UN in New York, Ms Simpson spoke to other pension funds and groups such as the PRI about the “systemically important carbon emitters”.

“This small group of companies, if they didn’t get their emissions down, we were never going to meet the goals of Paris,” she says. “They are going to take everyone else [down] with them.”

By December 2017, Climate Action 100+ had formed, initially with the backing of 225 investors with $26.3tn in assets. “We envisaged it would be a dozen or two dozen investors. But then it grew so fast. It was the right issue at the right time,” Ms Simpson says.

Setting targets

From the start, CA100+ was an investor-led group, with a couple of asset managers or asset owners taking the lead on engagement with each of the 161 companies it targets, which includes the world’s biggest emitters as well as groups that generate large levels of carbon in individual countries.

It outlined three expectations for businesses — that they set an emissions reduction target; report in line with the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosure, a framework backed by former Bank of England governor Mark Carney; and ensure boards were focused on global warming.

As of October 2019, 70 per cent of those 161 companies have made some sort of commitment to tackle emissions. There is no updated figure for this year. Recent successes include: AGL, Australia’s largest emitter, setting a so-called net-zero emissions goal for 2050; Indian oil and gas major Reliance Industries announcing a net zero emissions target for 2035; European cement companies CRH, St Gobain & HeidelbergCement also making similar commitments; and carmaker Ford outlining a plan to become greener.

One asset management member says: “What Climate Action 100 plus is beginning to achieve is absolutely huge.”

Others are less complimentary, including about its decision not to publish the names of the investors that led discussions with each company. It also does not disclose details about progress it is making at individual companies. Last year, a group of civil society organisations, including ShareAction, ClientEarth and Greenpeace International, wrote to CA100+ calling on it to disclose more information on how it was pushing the world’s top carbon emitters to act on climate change.

A senior figure at one non-profit says: “What is missing is a systemic approach to what they want from companies and how they get there. Instead when the year is over we get case studies, how the engagement went, how they got ‘ambitions’.”

CA100+ says it is working on publishing a “company level” update early next year.

It adds: “It’s important Climate Action 100+ is held to account and there’s an onus on the initiative to be as transparent as we can be, while also recognising that company and investor discussions and negotiations are often sensitive and commercial.”

Another concern is the structure of CA100+. In each region, a different group acts as the contact point for the organisation, such as Ceres in the US. “You can’t just speak to CA100+,” the official at the non-profit says.

Others worry that CA100+’s actions can slow down progress at some companies. Colin Baines, investment engagement manager at Friends Provident Foundation, says that while the group has achieved “significant results”, there have been “some controversial decisions”.

French oil company Total is one example. Ahead of the annual meeting this year, where a resolution aimed at forcing it to set hard targets was due to be voted on, CA100+ issued a statement with Total backing a less taxing plan.

The shareholder resolution was “perfectly aligned with CA100’s stated objectives”, says Mr Baines. He argued the “intervention [by CA100+] undoubtedly had an undermining impact” on the AGM vote with some investors using it as an excuse not to back the proposal. Friends Provident was one of the co-filers of the resolution and is not a member of CA100+, but other co-filers are members.

“CA100+ does need to be cognisant of being used as cover by asset managers wishing to tick an ESG engagement box but unwilling to oppose management,” Mr Baines says.

CA100+ says Total has made progress and engagement will continue.

The group was also notably missing from some of the biggest climate resolutions this year, including at Australian companies Woodside and Santos, which saw landmark votes on proposals to set hard climate targets. The resolutions were filed by the ACCR, rather than the investors leading the engagement on behalf of CA100+, although CA100+ made its members aware of the resolutions.

There are also accusations that companies are using their interactions with CA100+ to give the appearance they are taking climate change seriously, while often only outlining ambitions for 30 years away with little or no plan for what happens over the next decade or two.

“The unintended consequences of Climate Action 100+ is that climate action is delayed. All of these oil companies are using the CA100+ backing as a fig leaf,” says another official at an investor group.

The first step in a long process

But Ms Reynolds says the initiative is based on a step-by-step approach. Getting companies to set an ambition to cut emissions by 2050 is only the first goal, she says.

“We need that step to happen. These large companies are making those commitments knowing that they will now need to figure out how to make it [work],” she says.

“The beauty of this is when people make public commitments, we can follow them.”

Over the next few years, CA100+ will be closely watched to ensure it is living up to its pledges. Before the end of 2022, the group will also have to make a decision about its future, including whether to include more companies such as banks.

But there is no denying that CA100+ can drive change, says Matt Christensen, global head of responsible investment at Axa Investment Managers.

He argues CA100+ demonstrates how the investment industry can work together, rather than relying on hundreds of asset managers and pension funds to individually tackle companies.

“While not perfect, it has been a success story. It has moved the needle on climate issues,” he says.

Comments