Keeping a close eye on remote workers puts noses out of joint

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A little over a year ago, when the World Health Organization declared the planet was facing a pandemic, few could have predicted how far the nature of work would be transformed. When desk jockeys swapped familiar cubicles for the familial four walls, they did not think they were making a permanent transition to a hybrid or even entirely remote lifestyle.

For many managers, the exodus of employees has triggered fears of a collapse in productivity, even as margins are squeezed hard. Some believe the solution is software that can track workers’ every move online, keeping them honest out of fear.

For business students, this is a teachable moment. It is a chance to recognise that social problems cannot be solved with technical fixes, especially those with ethical risks that are likely to echo down the years. Instead, the disruption of coronavirus requires a cultural shift and acceptance of the new normal.

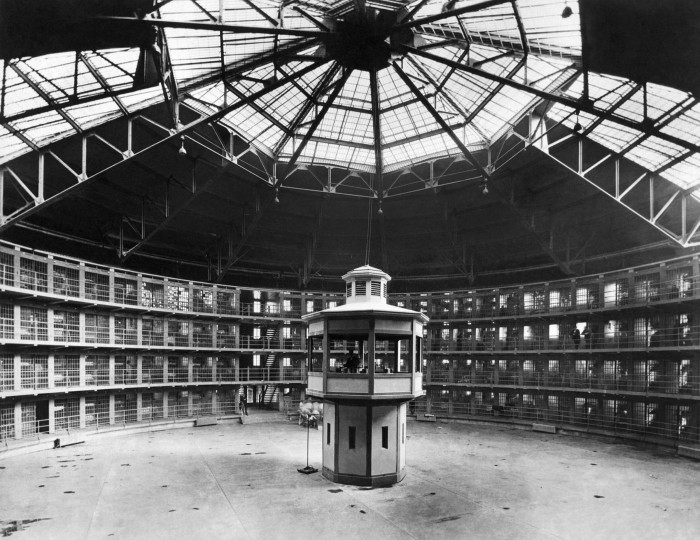

Offices have a “soft” notion of monitoring built in, simply from the presence of co-workers and bosses. While the existence of add-ons and shortcuts for hiding tabs on computer screens suggest that employees are not always hard at work, the panopticon effect of a shared workspace has long been assumed to benefit productivity.

Monitoring has only become more endemic in recent years as social media moved from niche to necessity. Stories of bosses discovering evidence of job applicants’ alcohol-related indiscretions have long circulated online, as have posts of employees lambasting their seniors, forgetting that they were Facebook friends. The idea of a total separation of personal and professional lives seems quaint in the digital age.

But there is something about employee-monitoring software that feels like a step up from this. The tech comes in a variety of forms: from programs that can give a readout of what each employee has been doing, along with screenshots, to always-on webcams, giving a sense of being under an all-seeing eye.

“There’s a lot of anxiety for managers,” says Jory MacKay, blog editor at productivity tech company RescueTime. The business has fielded inquiries about whether it offers monitoring of employees, MacKay says, though he emphasises that its products are for personal use only.

From an employers’ perspective, the proliferation of such tools — at a time when trimming overheads is key and there is a risk of commitment falling by the wayside — may seem like a godsend. In an age of Big Data, reducing employees’ productivity and value to a series of points on a curve appears a scientific way of approaching performance.

But such an approach raises several quandaries. At the most basic level, there are concerns around data protection and privacy. Employers face the risk of storing sensitive personal data, given that work laptops are often home laptops, as well as worries about effectively spying on domestic life.

Then there is a more social aspect: the way in which reducing productivity to numbers on a spreadsheet misses subtler human contributions. Reducing workers’ value to a simple score of time spent on “productive” or “wasteful” sites risks glossing over their talents and what else they bring to a company, such as in generating ideas or supporting and nurturing colleagues.

Even the productivity argument is questionable. A recent paper in the New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations noted that several studies on surveillance of workers have suggested these systems undermine their purpose, lowering trust in employers and reducing the quality of employees’ work.

“You have to have a wholesale movement to trust-based employment,” says Tariq Rauf, founder and chief executive of virtual workspace company Qatalog. “It’s not just about the change in your working practices but also the expectations.”

Rauf says asynchronous tools for messaging — from Slack to the humble email — will be part of the solution in the longer term, as many employees continue working in a hybrid way, partly on company premises, partly remotely. These tools are vital to preventing those working at home from being inadvertently left out of the loop.

But he also emphasises that the fundamental change must be mental: “I think the world is going to shift into a higher trust environment, and employers have to — they don’t have a choice.”

Other forms of technology can help with productivity — but on employees’ terms. Companies such as RescueTime show how the “quantified self” can be a powerful tool for improving our productivity. The company’s software puts screen time into categories and can block distracting activities for a set period. But importantly, users themselves decide whether to allow this.

The plethora of new digital social spaces, such as virtual conference halls, also offer inventive ways for workers to engage and build connections and trust with each other and their employer, without an overshadowing sense of paternalism or surveillance.

There will be many such dilemmas for business leaders in the coming years, where the easy and seemingly intuitive path may prove costly. This is especially the case with new technology which, once implemented, can be expensive and difficult to remove. Those leaders’ focus should be on the longer term, with an eye to understanding the human element of data. Reducing workers to automata in calculations of their worth could be a highly expensive error.

Comments