Micro-lending market takes rising interest rates in its stride

Simply sign up to the Emerging markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Fund managers are optimistic that the booming market for impact lending to small businesses in developing countries can survive sharp increases in global interest rates, after coming through the coronavirus pandemic relatively unscathed.

The global impact lending market has grown from $715bn at the end of 2019 to $1.164tn today, according to data from industry body the Global Impact Investing Network. This has been driven by surging investor demand for more ethically-minded investments and products that can make a positive difference to society or the environment.

Much of this growth has largely taken place in an environment of low global interest rates, supported by trillions of dollars of quantitative easing by western central banks, which made for easier conditions for borrowers, globally.

But, with US interest rates shooting up from near-zero to between 4.5 per cent and 4.75 per cent — their highest level since 2007 — in less than a year in a move to tame inflation, the market for lending to micro businesses faces a serious challenge.

However, some analysts and fund managers believe that the structure of the market and the financial health and flexibility of the underlying borrowers mean that any rise in defaults will be limited.

“There’s not a lot of panic yet,” says Antonio Fatás, professor of economics at business school Insead. “There’s no doubt there are some investment projects that don’t make sense at a higher interest rate. But I don’t think everyone in these markets is on the edge.”

The impact lending market has grown as part of an effort to plug the estimated $5.2tn funding gap faced by about 65mn micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries each year, according to the International Finance Corporation. This gap is particularly acute in Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and north Africa.

Micro and SME borrowers are key providers of jobs and growth in developing countries — and they can range from a smallholder in Mali borrowing money to buy a cow and sell the milk, or a woman in Tajikistan running a small catering business for schools and weddings. But, with very likely no access to bank lending, their funding options are typically limited to friends and family, local loan sharks who can charge more than 1,000 per cent interest per year — or impact lenders.

Managers running impact funds — whose investors could be government-run development finance institutions or institutional investors — tend to make loans to intermediaries in the developing country, which then provide financing to a wide range of end borrowers.

The structure of the market has meant that interest rate increases have been passed on slowly so far, in part because some loans are fixed rate, or to allow the intermediary time to absorb and pass on the higher rate to the end borrower.

“The sector has been quite slow to adjust but it is now,” says Chris Wehbe, chief executive of London-based impact lender Lendable. “It catches up with everyone.”

Wehbe’s company provides financing to lenders such as Egyptian salary advance firm Khazna and Bangladesh-based ShopUp, which works with small and micro retailers. He says Lendable responded to higher interest rates in the first half of last year by keeping lending rates the same but trying to attract a higher quality of borrower, then, in the second half, raising rates while still looking for better quality borrowers.

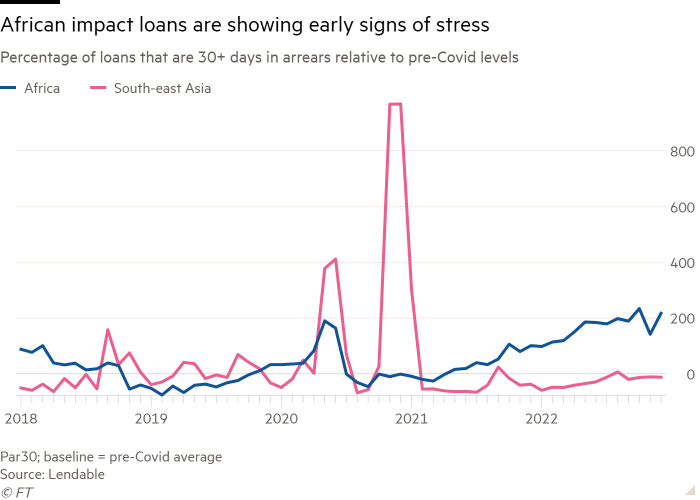

There has so far been no large surge in loss rates in the impact lending market, as was seen in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic. However, there are early signs that wider spreads over US interest rates could be creating stress for some borrowers.

That can be seen in the so-called Par30, a measure of loans in arrears for 30 days or more. While this does not necessarily mean the loan will be written off, it can point to future problems. In Africa, for instance, the Par30 is more than 200 per cent above its pre-Covid baseline, and higher than levels reached in the early stages of the pandemic, according to Lendable, which has a live view of lenders’ books containing about 38mn individual loans.

In contrast, south-east Asia suffered far more stress during 2020, but the Par30 there has fallen below pre-Covid levels — a sign that the region is coping well with the new economic environment.

Nevertheless, some managers argue that, having come through the fierce test presented by the pandemic, micro businesses are generally able to handle higher borrowing costs, and lenders are likely to work with them to help them adjust.

“During Covid our partners adjusted their lending terms to help [businesses],” says Michael Wehrle, head of investment solutions at impact lender BlueOrchard, which is part of Schroders. “Interest payments could be deferred. Our partners are more than pure lenders; they are responsible for their customers.”

Managers also argue that the increase in borrowing costs is small compared with the interest rates that borrowers already pay, while the strength of the local economy and the political climate are ultimately more important for a borrower than the cost of capital.

“In 2023, we’ll see some issues arising, but it doesn’t ring alarm bells,” says Theo Brouwers, head of impact investing at Dutch asset manager Actiam, which runs about €22bn in assets.

“If there’s a 1 per cent rise in interest rates, a very small percentage [of borrowers] may get into trouble,” he adds. “The risk has risen, but not as much as you’d think.”

Comments