Luscombe Farm and the rediscovered world of a postwar cultural dynasty

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

There are ordinary household cupboards, and then there are cupboards that reveal unknown worlds, like the doors that open into CS Lewis’s fantasy The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. One such portal was discovered by documentary director Clio David at her family home, Luscombe Farm in south Devon, one afternoon last summer. The cabinet – which she thought contained a jungle of bric-a-brac – housed a trove of more than 100 unseen paintings and drawings by her late mother, the artist Yasmin David.

“They were all so neatly stacked, it was almost as though she’d left them there waiting to be found,” says Clio, who grew up on the farm with her two siblings before moving to London at the age of 19. Mostly unframed, the canvases and watercolours depict nature in vibrant shades and vigorous brushstrokes that render the light-infused Devon scenes almost abstract.

The cupboard, located in a bright Indian-yellow upstairs room that served as her mother’s painting studio, had been a private place. The discovery of the unsigned, untitled work cast a whole new light on Yasmin’s life as a female landscape artist as well as on a huge tranche of family history. Clio had started to catalogue the many works ahead of a planned exhibition but this find was a turning point. “I took them out one by one and, oh my God! There were five big, square landscapes, drawings and smaller works. I thought, we’ve really got something here,” she recalls.

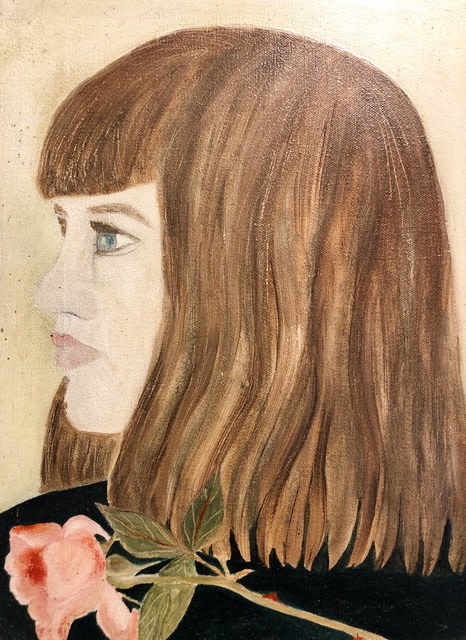

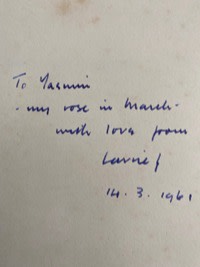

Born in 1939, Yasmin, who studied art in Sussex, came from a family that is intricately intertwined with the cultural firmament of postwar Britain. The tree expands to English poet Laurie Lee (Yasmin’s biological father); beauty and muse Lorna Wishart (her mother, who was married to publisher Ernest Wishart and was the lover of both Laurie Lee and Lucian Freud); to the poet Roy Campbell (her uncle); artist Michael Wishart (brother); Douglas Garman (her uncle, who had a long affair with Peggy Guggenheim); and to Kathleen Garman, the collector, dealer and second wife of sculptor Jacob Epstein. Their lives, loves and passions are chronicled in Cressida Connolly’s book The Rare and the Beautiful: the Lives of the Garmans.

There is a nod to Lady Kathleen Garman in the retrospective of Yasmin David’s work entitled Into The Light (opening today) at The New Art Gallery Walsall, which was built to house the collection of Clio’s great-aunt. The Garman Ryan Collection, gifted to the Borough of Walsall by Garman and her friend the sculptor Sally Ryan, includes work by Picasso, Braque, Cézanne, Géricault and Delacroix.

This will be the first significant show of Yasmin David’s work, and with the cupboard bounty, the scope of what can be explored has suddenly become richer and deeper. It serves as a chronicle of an undiscovered landscape artist who painted quietly and prolifically for more than 50 years. Her constant subject was the thriving, fertile south Devon countryside, renowned for its magical 20ft-high hedgebanks that turn the lanes into a wild maze, and its orchards and dairy farms around the River Dart, which courses into the English Channel.

“My mother always worked from her own place, building her practice steadily over time. Her paintings are unique, and yet sit within the romantic English landscape tradition that zigzags from Richard Long and Paul Nash to Turner, and the pastoral visions of Samuel Palmer to William Blake,” says Clio. “She made that tradition her own, among other postwar female artists.” Together with her film editor husband, Chris Dickens (Slumdog Millionaire and Rocketman), Clio has made a short introductory film for the gallery site.

Yasmin and her husband, Julian – a Jungian analyst, therapist and teacher at the liberal arts school Dartington Hall (alumni include Lucian Freud, songwriter Kit Hain and literary editor Miriam Gross) – bought the tumbledown Devon dairy farm at auction in 1961. One wing of the house dates back to the 11th century. “No one else wanted it, the floorboards were falling through. Our three children were growing and I was pretending I was a farmer – producing milk, losing money, teaching and making cider,” recalls Julian David, sitting by the fireplace wearing a smart ivory summer blazer. “There were still a lot of dialects in this area at that time and we loved that it was the real thing.” The cider press turned into a successful venture and the Luscombe organic drinks brand (producing 9.5m bottles per year) is now run by his son, Gabriel, who lives in a converted barn on the estate. Clio’s sister, Esther, an artist too, lives nearby and is married to dairy farmer Oliver Watson, of the Riverford Organic dynasty.

Over the years, the couple turned Luscombe Farm, with its giant flagstone floors and peeling plaster walls, into a home. Today, with guinea fowl and ducks in the yard, barns, outhouses, a running stream, a romantic Italianate garden and orchards, it appears like a reverie in the late-spring sunshine. “My mother was particular about how she wanted it to look – partially wild and untouched – and we kept it like that. Family, the farm, nature, painting… This is how she lived and she was just not interested in the art market,” says Clio, who was married in the iris- and rose-planted walled garden at the house.

Yasmin never showed her work during her lifetime. “She had a skin too few,” remarks Julian of her sensitivity. “The pictures found in the cupboard? I’ve never seen them before. She painted the whole time and I would come across things and hang them up.

“The day before she died, she said: ‘Jules, I’ve decided that I agree with you, my work is good’, and I read that as permission for me to show it. In her own lifetime, she could not bear the thought of people looking at stuff and perhaps not getting the point. The point would be in the picture itself,” adds Julian, who has created an informal gallery within the house.

Despite – or perhaps because of – the fact that she hailed from an extraordinarily colourful bohemian family that helped to shape culture and thinking in postwar Britain, Yasmin rebelled into privacy. The oils and watercolours, far from polite and picturesque, capture nature in all its beguiling and turbulent glory. Looking at a big canvas that hangs above the kitchen table on a terracotta-painted plaster wall, the effect induces a strange synaesthesia. One can almost hear the woodland stream that gushes through the centre frame and smell the emerald and citrine lady ferns, lichen-clad oak branches and wild garlic. “She loved to watch the windy, watery, ever-changing light and seasons, which she painted mainly from her memory, but she also kept a notebook,” explains Clio. One entry reads: “Jan: soft, cooler wind from the south-west, rain smelling – sky over the sea pale duck-egg blue washed with yellow – the sea itself murmuring gently, and behind the house (deeply, out of the bushes) a wood pigeon softly bubbling and re-winding down long, deep chambers of the inner ear.”

Other works are more meditative, evoking the transcendent power of nature that Yasmin witnessed in the rapidly changing light, rolling clouds, hill tops and valleys. One of her favourite studies was the view from a stretch of steep Devon lane that rises up in front of Luscombe Farm. She often painted in a cabin studio, kitted out with a burning stove in the grounds. “She always sought out the brilliant light, and we spent time in South Africa and Sicily. Yet spring in Devon is inimitable,” Julian says.

There is more to this discovery than the paintings alone. Clio also retrieved a stash of correspondence and paper clippings at the back of a rickety chest. The long letters written in ink and on flyweight paper are between Yasmin and her poet-writer father, Laurie Lee. Through a bit of sleuthing, Yasmin discovered she was his illegitimate daughter and tracked him down in her early 20s. Father and daughter forged a relationship with the tender letters revealing their shared love of poetry, art and the English countryside. “It was simply the greatest occasion of my life,” Lee wrote of their reunion. Their relationship remained clandestine until Lee’s death in 1997, at which point the tabloids revelled in the “secret love child” scandal. “I can understand why she did not show her work as there was such a huge amount inside her and she was growing as an artist. There is a side of her I am understanding more and more now,” says Julian.

Yasmin David’s work is now attracting serious critical attention. “In the postwar period, David’s work sits in comparison with that of Joan Eardley, Barbara Delaney and Gillian Ayres, women following in the footsteps of those of the St Ives milieu in the 1930s: Barbara Hepworth in the field of sculpture, and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and Margaret Mellis,” writes art academic Dr Sophie Hatchwell. “Her work offers a way into thinking about the British landscape outside of traditional patriarchal frameworks – that is, as a territory to be conquered or husbanded.”

Indeed, this will be the summer of overlooked and hidden female artists – in the UK, at least. Into the Light runs concurrently with Breaking the Mould, an exhibition of female sculptors at Yorkshire Sculpture Park with work by more than 50 artists including Rana Begum, Lygia Clark, Cathy de Monchaux, Elisabeth Frink, Anthea Hamilton, Holly Hendry, Barbara Hepworth and Rachel Whiteread. At Charleston in East Sussex, more than 50 works by the flamboyant artist Nina Hamnett, enmeshed in the Bloomsbury group, are currently on display. “There is a resurgence of interest in 20th century female artists. When you think of how many were practising, it is amazing how little has been told,” Clio concludes.

Yasmin David: Into the Light is now on at The New Art Gallery Walsall until December 2021

Comments