Investors yearn for the catharsis of hitting a market bottom

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For a minute there, at the start of this week, markets looked . . . what’s the technical term? OK?

A brutal sell-off in stocks, which made the previous week the worst since the pandemic struck in the spring of 2020, suddenly turned round. A holiday in the US on Monday kept a lid on trading, but Tuesday brought that rarest of things: a sudden lurch higher.

Perhaps under the influence of the delightful sunshine gracing London at the time, one banker took this as a reason to be cheerful. “Give summer another chance!” he enthused in a note to clients. “Players want to buy equities again. Will it be more sticky this time around? We shall see.”

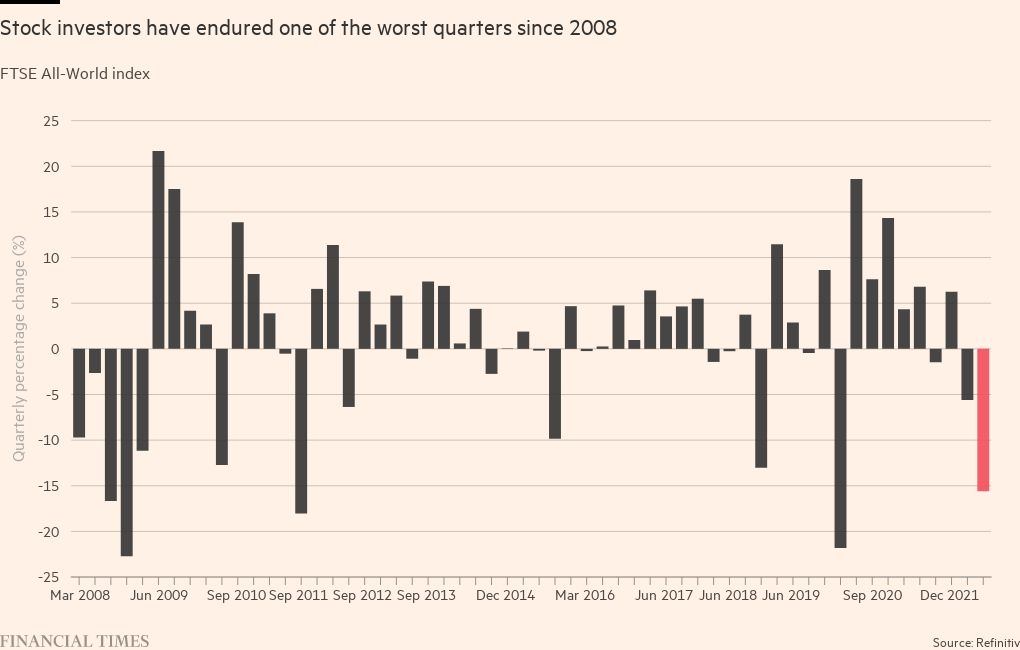

Reader, it was not more sticky this time around. The positive mood did not even leak into the following Asian session. But the brief moment of cheer reflects a sense that investors are growing slightly desperate for the horror show that is the first half of 2022 to be over. Haven’t we suffered enough? After all, if you exclude the first quarter of 2020, this has been one of the worst quarters for global stocks since 2008. Surely the hour has come for heroes to time the market to perfection and buy?

On paper, yes, absolutely. “Valuations are starting to look appealing in a longer-term context,” UBS Global Wealth Management noted in its second-half outlook. “The historical relationship between price-to-earnings ratios and future returns would suggest it is reasonable to expect US equities to produce 10 per cent annual returns over the next decade.”

But not yet, alas. The week may end up mildly positive but the real turn in fortunes remains elusive. UBS, like many other investors, remains “neutral”, noting a significant risk of large further falls from here.

Tatjana Puhan, the deputy chief investment officer at French asset manager Tobam, describes herself as an optimist by nature. “My glass of water is half full,” she says. But she is baffled at the urge to spot an end to the bleeding in markets.

“I find it ridiculous,” she says. “The financial TV was saying ‘markets are positive, maybe we’re through the worst’. Are you kidding me? Why would you be positive all of a sudden?”

She has a point. The war in Ukraine is not going to magically and quickly disappear. That will keep food and energy prices high and inflationary forces firmly in play. Central banks are jamming interest rates higher, and investors are not hugely convinced that policymakers can avoid a hard landing — a euphemism for crashing the economy — particularly after their previous confidence in transitory inflation turned out to be misplaced. Even Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell has now acknowledged that a US recession is “certainly a possibility”.

Quantitative tightening — the clunkily named process of central banks offloading the assets they bought to support the system in recent years — has also only just begun, and still, no one honestly knows what it will mean. “It’s a huge debate,” says Peter Fitzgerald, chief investment officer for multi-asset and macro at Aviva Investors. “Some people say these things are priced in,” he says. “It’s never priced in.”

In addition, Puhan is among those who believe that even after some large drops in share prices, many investors are still unwilling to give up on the heavy-hitting tech stocks that dominate the US market.

“They are still considered safe investments,” Puhan says. At some stage, investors will properly latch on to recession risks that she considers to be broadly underestimated. And at that point, the super-stretched elastic band of market valuations can snap. She thinks markets can drop by a further 20 per cent before the year is out. “It’s absolutely possible,” she says.

That is not an overly cheerful message, especially from a self-declared optimist, and it may be little consolation for investors — retail and professional — keen to rebuild bruised portfolios.

Kate El-Hillow, chief investment officer at Russell Investments, says that after the worst start to a year in three decades for bonds and one of the worst in the S&P 500 in a century, she wants “to get this re-rating to happen, and get to the other side”.

In part, that is because “the other side” is where you can pick up some bargains and rebuild portfolios. “It’s a good time to think about ‘where am I going to deploy?’,” she says. In addition, though, speed is a virtue in itself. “We want it to happen a bit quicker, while consumer and corporate balance sheets are still strong.”

This is the fund manager’s equivalent of getting that root canal surgery done sooner rather than later. Yes, the synchronised decline in risky assets is unpleasant, but if we can get it done fast, then markets might have time to stabilise before companies and households run out of the financial padding they built up in the heyday of cheap money.

Markets and real life do not always move in tandem — the economic crash of 2020 coincided with a massive rally from March of that year onwards, for example. Maybe now, markets can carry the burden. Embracing the pain might be the best way forward.

Comments