UK companies’ gender pay gap reporting drops

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

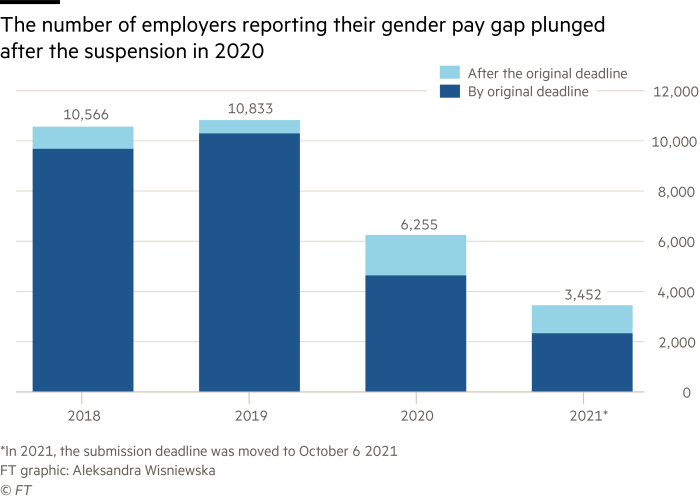

Only a quarter of the UK companies normally eligible to report their gender pay gap data did so in time for the April deadline this year — raising concerns that a continued hiatus on enforcement is delaying progress in closing the gap.

A decision by the UK government to suspend the gender pay gap reporting requirement entirely in 2020 — and to delay this year’s deadline to October — had been intended to ease the pressure on companies battling the Covid-19 crisis. But it has sent a worrying message to women, who have been dis-proportionately affected by the economic fallout from the pandemic.

“We absolutely had the proof in the past 12 months that, if you do not enforce, companies won’t report,” says Caroline Nokes, MP and chair of the parliamentary women and equalities committee. “And if they don’t report, you have zero confidence that they do the right thing. Only if you shine a spotlight on something, [do] you get change.”

The number of organisations submitting pay gap figures fell from nearly 11,000 in 2019 to 6,200 in 2020 — a 42 per cent drop on the period before the pandemic. This year, only around 2,500 companies reported before the original April deadline — a quarter of the 10,000 companies that are eligible to report. Analysis by the professional services firm PwC found that those that did report by April were mostly in sectors least affected by the pandemic.

More companies have reported since April, bringing the total to around 3,400 so far, ahead of the new October deadline. This current reporting period, ending in April 2022, is the last one before the secretary of state is set to review the rules.

Gender pay gap reporting was introduced in the UK in 2017 as a mandatory requirement for employers with more than 250 employees. They had to submit their mean and median gender pay gaps, bonus pay gaps, and the proportion of men and women in each pay quartile. Since the requirement was introduced, the gender pay gap has been in slight, gradual decline.

“Suspending gender pay gap enforcement was proportionate and the right thing to do,” says Alastair Pringle, interim chief executive at the Equality and Human Rights Commission, which is responsible for enforcing reporting. “The pandemic and lockdown have had, and are still having, a huge impact on employers. Offices were closed overnight and many industries were completely shut down.”

The EHRC has recommended that the government make it mandatory for companies to publish action plans alongside gender pay figures, and to empower the EHRC to issue fines.

“It would be effective as an immediate sanction for late reporting,” says Pringle.

The government’s equality hub says the government is “fully committed to women’s economic empowerment” and points to the “unprecedented levels of economic support” offered to protect jobs for both women and men.

However, others are concerned by the government’s decision to suspend and then delay the reporting requirement.

“It sends the wrong signal that the topic is only important in good times,” says Denise Wilson, chief executive of the Hampton-Alexander review, the government-backed body that leads the task force for increasing the number of women on boards.

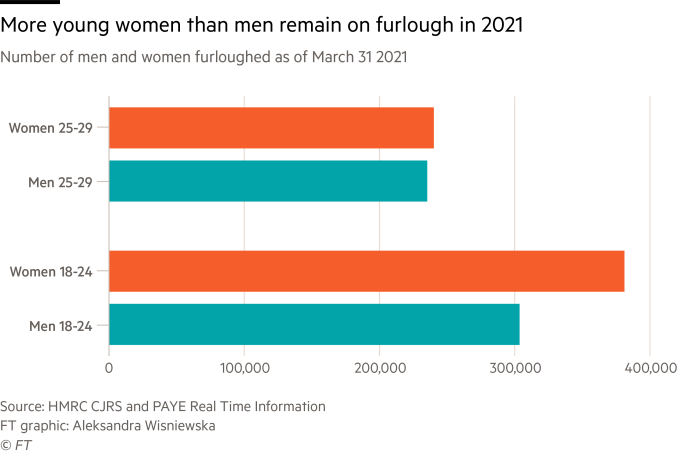

According to a recent report by the women and equalities committee, women across the UK were more likely to ask for furlough, be furloughed, lose jobs and miss out on the discretionary top-up to furloughed earnings.

“Even before the pandemic, young women were more likely to be on zero-hour contracts, have insecure jobs, were paid less than their male counterparts and faced a career of earning tens of thousands pounds less than men,” says Joe Levenson, director of communications and campaigns at the Young Women’s Trust.

The pandemic has exacerbated these inequalities and the government’s response falls short, say critics. “The recovery plan is very broad-brush and we have yet to see anything gendered [in its response],” says Nokes, who argues that more initiatives to support women are needed.

After finding that the government’s investment plans were skewed towards male-dominated sectors, the women and equalities committee called this year for an equality analysis of the government’s pandemic support schemes. “I would really want to see the government return to the equalities agenda with some passion and drive,” says Nokes.

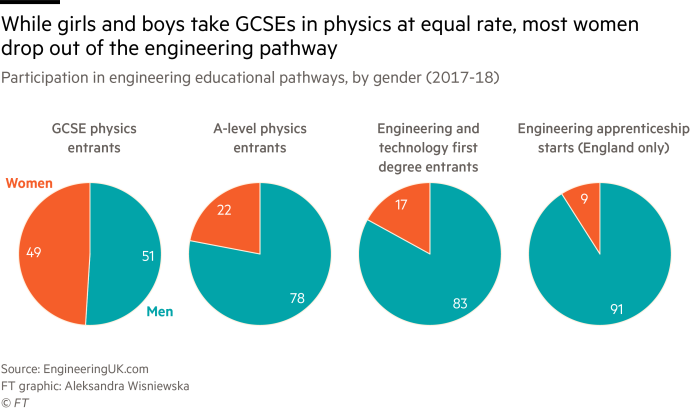

Ensuring more women enter the industries that are most likely to flourish post-pandemic will be key, says Ann Francke, chief executive of the Chartered Management Institute. She notes that fields such as technology, green energy and infrastructure were growing six times faster than others even before Covid — and yet are male-dominated.

More stories from this report

“We urgently need to get young women into these fields,” she says. “It’s a once in a generation opportunity to learn from the crisis and make the workplace a better place. If we don’t do that, we’ll go even more backwards.”

The future shape of flexible working is still being debated, but it may prove to be a significant advantage in competition for talent, says the Hampton-Alexander review’s Wilson. Organisations that opt not to offer continued flexibility could become less attractive employers.

“Women need to take a close hard look at the culture of those organisations and ask, ‘Is that for me?’. Any organisation that isn’t looking at that and making changes would ring the alarm bell,” Wilson says.

Comments