Natural gas vies for big role in shift to low-carbon economy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Beast from the East cold snap that gripped north-west Europe this year provided a sharp reminder of the fragility of energy supplies. As temperatures plunged and demand soared, European traders were scrambling for natural gas.

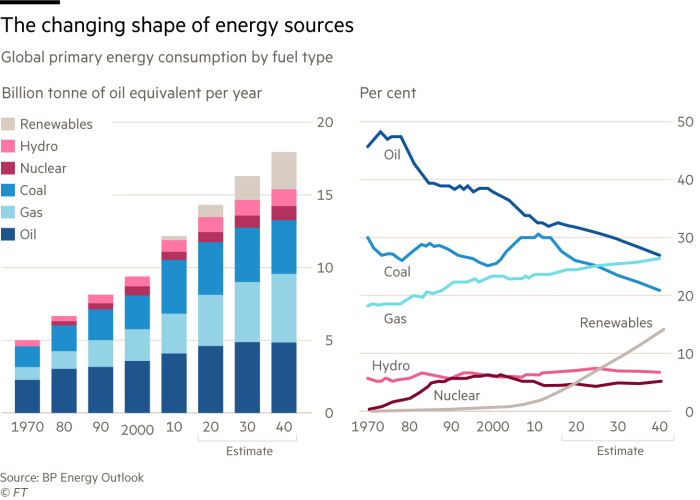

The Arctic-like freeze was an illustration of the continuing importance of natural gas in the energy supply mix at a time when renewable power is growing. Europe is not alone. The latest BP Energy Outlook report forecasts that natural gas will grow globally much faster than either oil or coal to 2040. A combination of factors — from increasing levels of industrialisation and power demand, to continued switching from coal to gas — will drive that growth.

Compared with other fossil fuels, gas is regarded as relatively clean. It emits half as much carbon dioxide as coal when burnt to generate electricity and at least 75 per cent less nitrogen oxides and other particles that harm health.

Most people in the industry argue that gas can play a big role in a future energy supply dominated by renewable power because it would provide a stable source of electricity when the wind does not blow or the sun does not shine. That view has been taken up among the world’s energy groups, which are all investing heavily in gas projects.

Wood Mackenzie, the energy consultancy, expects demand for gas to increase globally by 1.9 per cent a year up to 2025, when it will fall to 1.3-1.4 per cent a year up to 2035 as demand, especially in the power sector, starts to decline.

China and other emerging markets continue to dominate demand for gas. Natural gas had a strong year in 2017, with consumption up 3 per cent and production up 4 per cent - the fastest growth rates since immediately following the global financial crisis according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018 published this week.

The single biggest factor fuelling global gas consumption was the surge in Chinese gas demand, where consumption increased by over 15 per cent, driven by government environmental policies encouraging coal-to-gas switching.

The other factor supporting the strength of global gas markets last year was the continued expansion of liquified natural gas (LNG), which increased by over 10 per cent in 2017, its strongest growth since 2010, according to BP. China’s increased need for LNG accounted for almost half of the global expansion. The country overtook Korea to become the world’s second largest importer of LNG after Japan.

Massimo Di Odoardo, vice-president of global gas and LNG research at Wood Mackenzie, says China will become the largest LNG importer by the mid-2020s.

The Chinese demand has reinvigorated the global LNG industry. Malaysian company Petronas last month said it would take an equity stake in Royal Dutch Shell’s Canadian liquefaction project, marking a U-turn after it cancelled its own proposal in west Canada last year.

BP expects global LNG supplies to more than double to 2040. It sees exports being dominated by Qatar and the US where the boom in shale resources has boosted American supplies and turned the country into a net exporter of gas. The two countries are expected to account for 40 per cent of global LNG exports by 2040.

Europe will remain reliant on imports and Wood Mackenzie expects it to become increasingly interested in LNG shipments as its domestic supplies decline. The much-heralded shale gas boom in eastern Europe of a few years ago, which held out hopes of a new source of supply, has not materialised. In the UK, efforts to commercialise deposits have been held up by opposition to hydraulic fracturing, which is required to release gas from shale rock.

“It will be difficult to replicate the US shale boom in Europe because of population density, environmental concerns and different systems of property rights,” says Simon Virley, a partner and head of energy and natural resources at KPMG, the consultancy.

Most of the world’s big energy companies continue to count on demand for gas outlasting that for other fossil fuels given its relatively “clean” characteristics. However, in its recent position paper, BP noted that the scale of increasing gas demand up to 2040 “could be adversely affected by either weaker or stronger environmental policies”.

Nevertheless, industry executives argue that under any scenario gas will be needed during the transition. The dash for gas has further to run.

Explore the rest of our stories on Energy Producers

- Solar and wind power surge marks production shift

- Big Oil harnesses power of data analysis to ensure survival

- High costs and renewables challenge the case for nuclear power

- Coal fades in developed world but is far from dead in Asia

- Opinion: Forecasters have an awful record in predicting energy markets

Comments