Andy Warhol and the power of the Polaroid

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Looking at a Warhol Polaroid now makes me feel like I’m getting the inside scoop from the artist himself,” says Amanda Hajjar, director of exhibitions and one of the curators of the upcoming show Andy Warhol: Photo Factory, opening at Fotografiska New York on 10 September. “It’s a test print for a concept. I love feeling like I’m in the studio with him.”

Photo Factory represents a substantial study of Warhol’s work on film. It comprises Polaroids, gelatin silver prints, films, photobooth strips and stitched photographs, which Warhol physically sewed together in consecutive grids of four, six, and 12 images. Twenty out of the 120 images on display have sat in private collections up until this point, never exhibited.

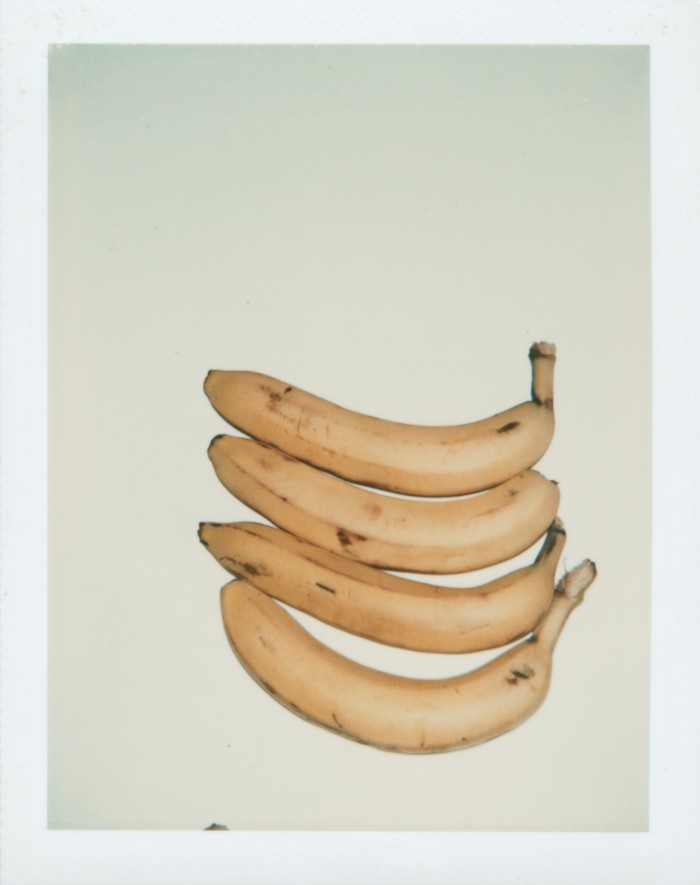

The show demonstrates precisely what is so enduringly beguiling about the Polaroid as a medium: intimate, raw, unguarded, it allows us a glimpse behind the scenes, an insight into a thought process. One example shows an arrangement of bananas against a white surface – what would become Warhol’s famous series of banana screen prints.

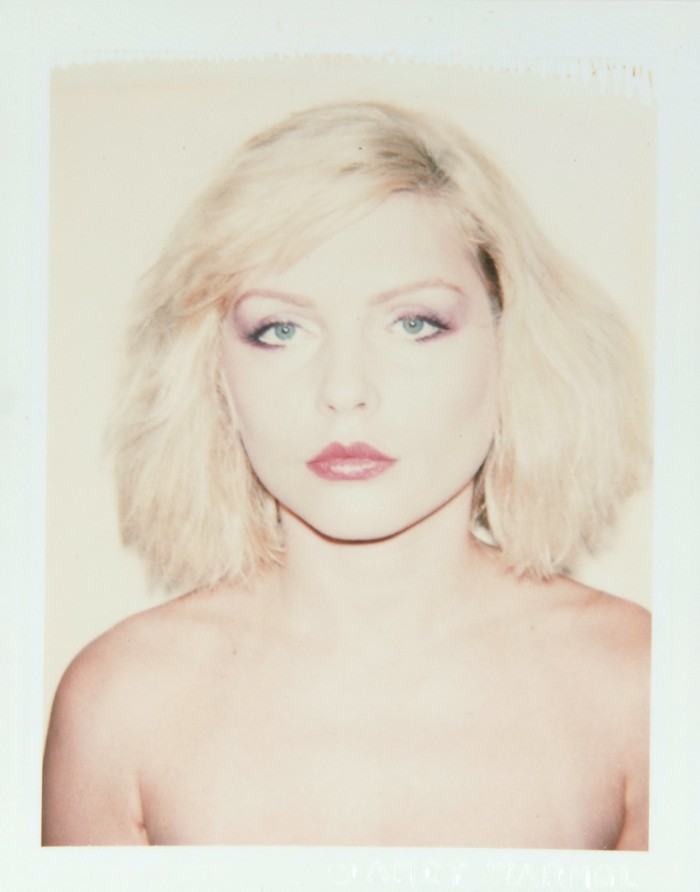

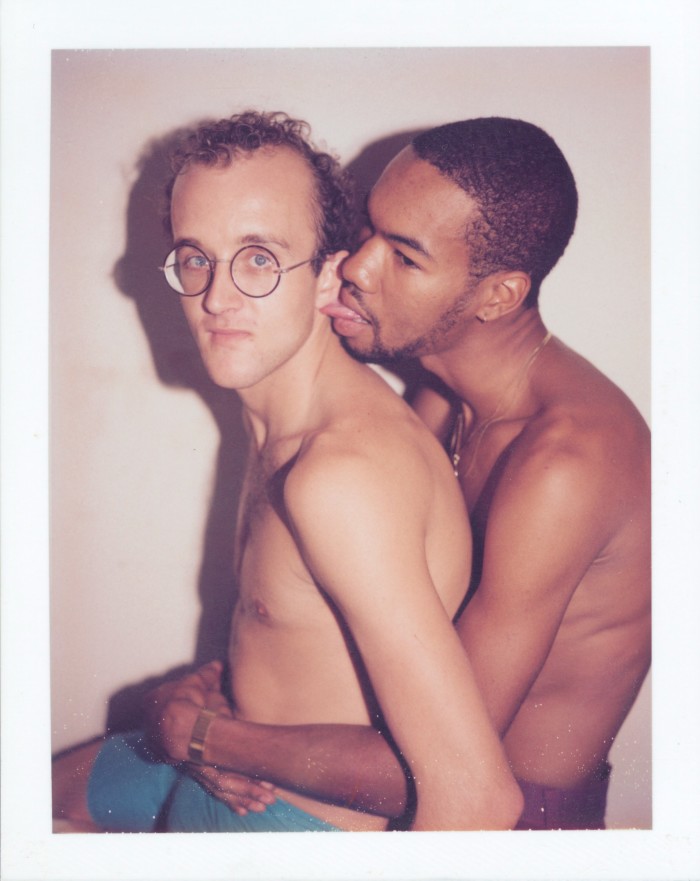

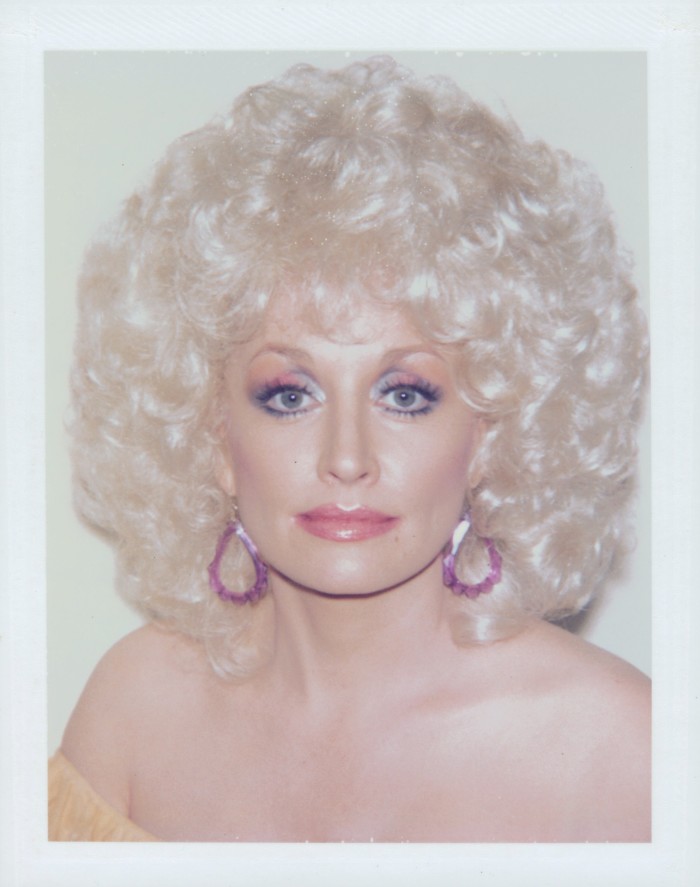

Other images allow an insight into his starry circle of friends. A Polaroid from 1985 captures Dolly Parton coiffured and made-up as if about to walk out on stage, but close up her face is blank and emotionless, as if she’s accustomed to rather than thrilled by her own glamour. Carolina Herrera and Diane von Furstenburg are both captured fresh-faced and devastating, Grace Jones strikes bold poses for the camera, and Keith Haring lounges with a lover. “The immediacy of the Polaroid is so valuable, it’s a true relic from a specific moment,” says Hajjar. “It’s simple and easy, no fuss, which I think lends itself so well to experimentation.”

The Warhol show taps into a longstanding fascination with the form among collectors. In 2010, a Sotheby’s sale of photographs from the Polaroid collection, which featured snaps by David Hockney, Ansel Adams and Andy Warhol among others, raised just under $12.5m. “It was the first time in the history of the market that a collection based on a technology – rather than an artist or theme or period – came to auction,” explains Emily Bierman, Sotheby’s head of photographs in New York. In the course of the auction, the record for a Warhol photograph was broken twice, first with Self-Portrait (Grimace), which sold for $146,500 and then with Self-Portrait (Eyes Closed) which went for $254,500 – more than 15 times the high estimate of $15,000. A nine-part self-portrait by Chuck Close sold for $290,500 – “I believe the highest price achieved for any Polaroid work,” says Bierman.

“We live in a society that expects instant results and Polaroid technology really prepared us for the digital age,” she adds, of the Polaroid’s enduring popularity. “What is more gratifying than watching a Polaroid image develop?”

Likewise, Instant Stories, a reissued book by German filmmaker Wim Wenders, who has long used Polaroids to experiment with light and composition, collates 403 Polaroids chronicling his life in the ’70s and ’80s. From a snap of a coffee cup and a ketchup bottle on the table of a diner to a shot of his parked car in the expanse of the Utah desert, they make up a diaristic portrait of the peripatetic life of a young filmmaker.

The magic of the Polaroid is summed up by American street photographer Dawoud Bey. In a book on Bey published by Mack last year, writer Greg Tate recounted how the photographer would use a large format tripod mounted camera and a unique positive/negative Polaroid film to create both an instant print and a reusable negative from which he would create his prints. After taking someone’s portrait, Bey would give each person a small black-and-white Polaroid print for themselves. As well as an act of thanks it was a way of giving the subject a form of ownership over the artwork. The Polaroid was a different print than the finished works Bey went on to make but, like Warhol’s Polaroids, it was just as much a work of art: each subject’s own original.

Andy Warhol: Photo Factory is at Fotografiska New York from 10 September until 30 January 2022

Comments