Equity markets signal it is time to diversify

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is chief market strategist for Emea at JPMorgan Asset Management

How worried should we be about stock market valuations? In my day-to-day conversations with clients, it seems that investors are unsure.

On the one hand, they can see the US economy is bouncing back quickly, vaccines are being rolled out more rapidly in continental Europe and both governments and central banks are in no rush to rein in stimulus. For the global economy, the good times look set to roll.

At the same time, stock valuations in many regions are troubling. A key measure is the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio made famous by Robert Shiller. For US stocks, this is at a level that has only been seen at one other point in its 140-year history: the tech boom. And that was followed by a spectacular bust.

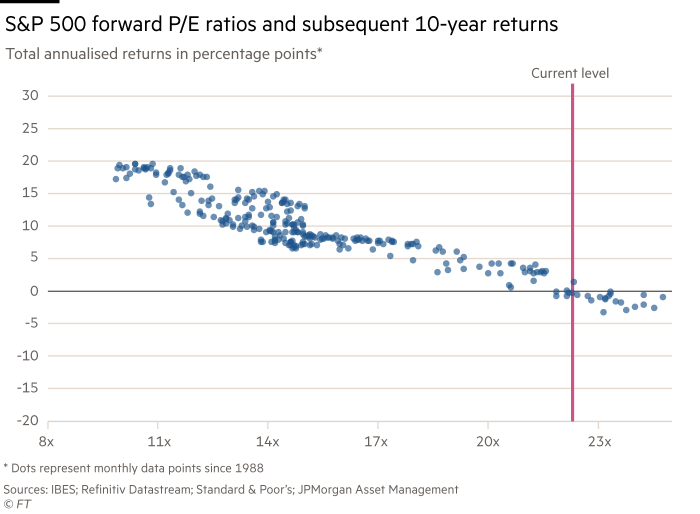

My preferred valuation measure uses one-year ahead forward earnings. With the S&P price index at over 22 times, this measure of earnings is still uncomfortably above the long-term average.

While valuations have little predictive power for near-term returns, the relationship with long-term returns is very strong. If the past three decades serve as a guide, then the current valuation points to an average annual return for the S&P over the next 10 years of . . . zero.

Is this time different? I’ve heard two arguments for why high valuations will not hinder long-term returns. One I find convincing. The other I do not.

The argument I am not persuaded by is that valuations are permanently supported by low interest rates. This cannot be right over the long term. Either policymakers have navigated the pandemic so well that equilibrium economic and earnings growth, and interest rates will revert to prior levels. Or there will be lasting scars. In which case, we will be stuck in a low nominal growth, earnings and interest rate environment.

It cannot be right that we will come out of the crisis with sustainably higher earnings growth and sustainably lower bond yields. Central banks may be distorting bond prices with asset purchases and other monetary tricks. But, at some point, in the face of rising growth and inflation, bondholders will eventually tire of continually negative real returns and sell those bonds, pushing yields higher.

The alternative argument, which is more compelling, is that valuations will not be problematic because the recovery in nominal activity will be more spectacular than analysts are predicting. Given S&P 500 company earnings are expected to rise 30 per cent this year and end the year more than 10 per cent above the pre-Covid-19 level, this might seem like a bold statement.

But one must not underestimate the potential for a boom in the second half of the year. US households accumulated “excess savings” of 8 per cent of gross domestic product last year. They are now in the process of receiving fiscal stimulus amounting to another 5 per cent of GDP.

If much of this money is spent in the coming months, then the bounceback could meaningfully exceed the forecasts of economists and equity analysts. This short-term boost to demand could have lasting growth implications if it creates a virtuous cycle of rising investment, employment and, in turn, more consumption.

It would be amiss not to recognise the sectoral nuance in the valuation debate. After all, it is a handful of technology and consumer discretionary stocks that have lifted the overall valuation of the US market. The top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 trade at a forward price-to-earnings ratio of 31 times on average. When you strip out these stocks, the forward PE comes down to under 20 times.

The tech giants reported their first-quarter earnings last week and, on the whole, the resilience of pricing suggests investors still believe their earnings outlook justifies their high price tag.

But there are sectors in which the market may be underestimating earnings prospects. Take the financial sector, for example, which has a price to forward earnings multiple of 14. Loan losses from the pandemic are turning out to be lower than many of the financials had provisioned. We may also see a recovery in loan growth and higher interest rates will also help the profit margins for banks on issued loans.

The implication is that while we should not ignore valuations, nor should we rely on low interest rates as their justification, there are still opportunities in stocks. In particular, investors should focus on areas of the market where analysts might yet be underestimating earnings growth. For much of the past decade, investors would have done perfectly well to have held a narrow portfolio dominated by US tech stocks. Now, however, is the time to diversify.

Comments