‘There is nothing else out there’: why Europe is hooked on Russian gas

Simply sign up to the EU energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

As outrage over the war in Ukraine grows, European leaders are under mounting pressure to expand sanctions against Russia and end the EU’s decades-long dependence on the country’s oil and gas once and for all.

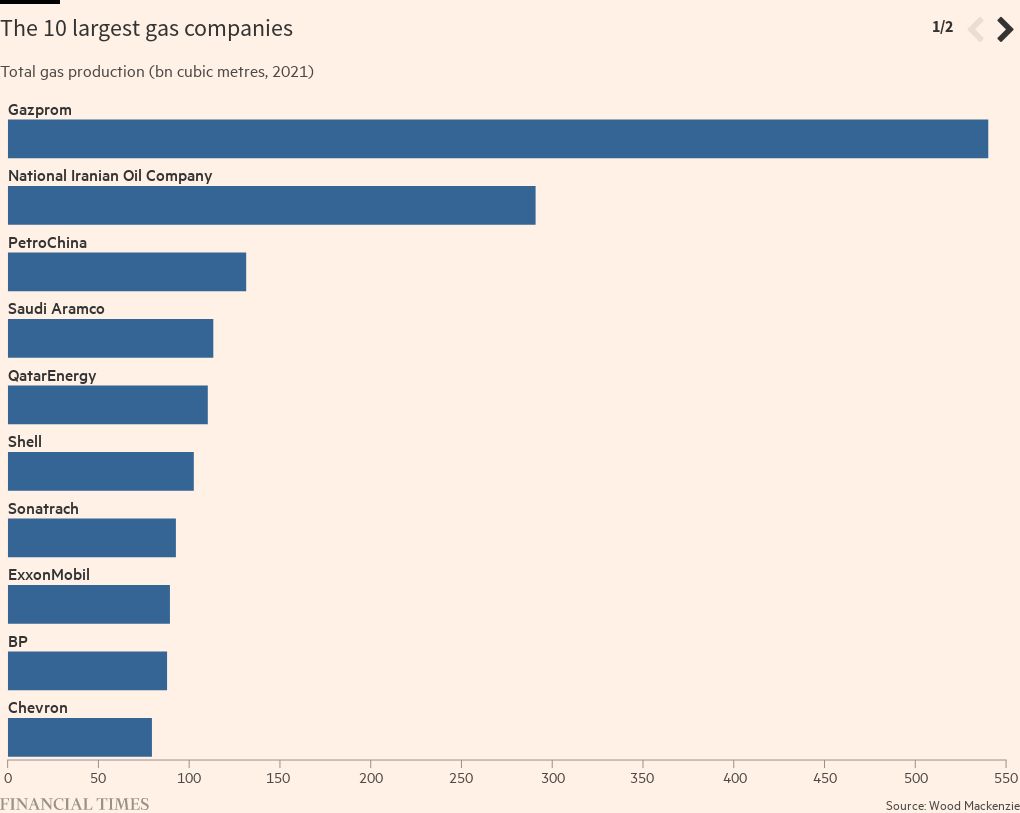

But an analysis of the top 10 global producers shows just how difficult it would be to remove Russian gas from the European energy mix without imposing stringent curbs on industrial consumption that could crush economic growth.

The EU imports about 30 per cent of its oil and 40 per cent of its gas from Russia, paying Moscow roughly $850mn a day at current prices to keep the hydrocarbons flowing. Weaning Europe off Russian oil would be challenging. Getting rid of Russian gas would be harder.

Gazprom, Russia’s biggest gas producer and monopoly exporter, towers over the global gas market. It produced 540bn cubic metres last year, more than BP, Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Saudi Aramco combined, according to data from consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

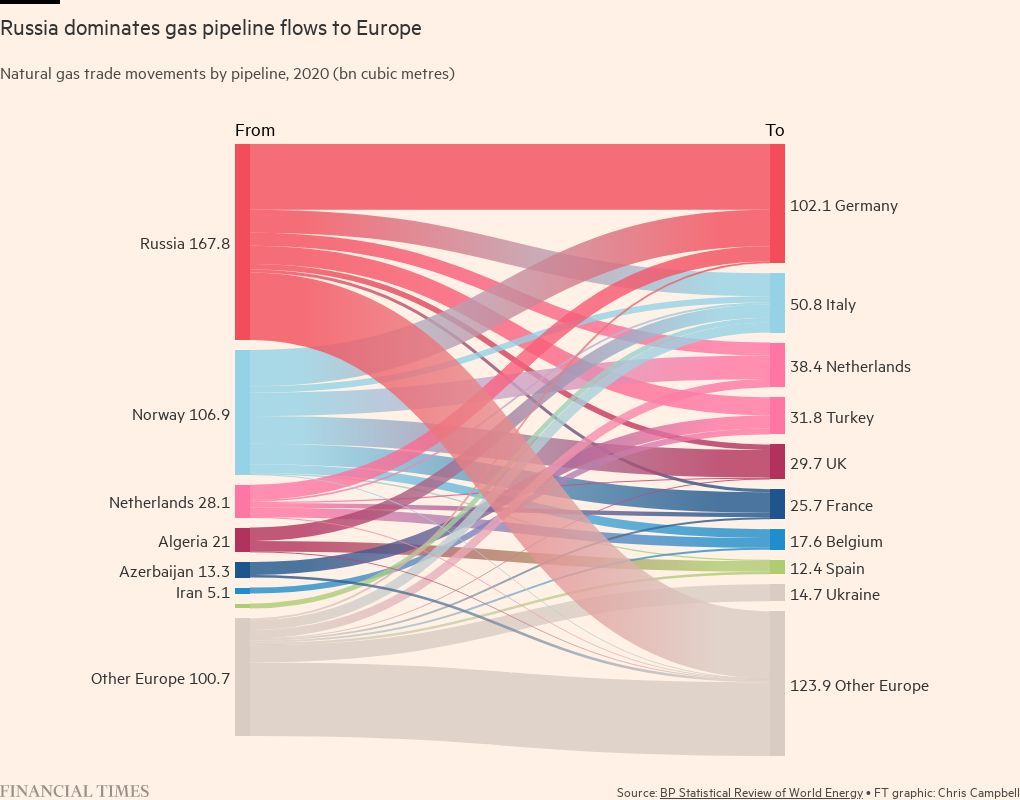

Of that, 331bn cubic metres were consumed in Russia and 168bn were piped to Europe.

Giles Farrer, head of gas research at Wood Mackenzie, said replacing that volume would be “impossible” since production at most gas projects around the world was already running at close to maximum levels. “There is nothing else out there.”

Unlike in the oil industry, where big producers such as Saudi Arabia have historically held back additional capacity to help balance the market in the event of a disruption to global supplies, the gas industry has tended to operate at or close to capacity.

Gas is also less fungible than oil, since moving it from the point of production to the point of consumption requires a pipeline or liquefaction facility and therefore a bigger upfront investment, said Farrer.

As a result, countries with significant gas reserves, such as Russia, have tended to develop large domestic markets before building export capacity.

The Iranian national oil company, the largest gas producer after Gazprom, produced 291bn cubic metres in 2021. But 280bn of that was consumed in Iran, according to Wood Mackenzie’s data.

The easing of sanctions on Iran in the event of a nuclear deal could reopen the possibility of broader international access to Iranian gas but would require new export facilities, which would take years to build.

Other than Russia, the only suppliers of piped gas to Europe are Norway, Azerbaijan, Libya and Algeria, where state-owned Sonatrach sent 34bn cubic metres via pipelines to Spain and Italy last year.

Algeria could increase that supply if it can resolve a diplomatic spat with Morocco that has blocked one of its routes to Spain since November, but it would first need to boost production and satisfy growing domestic demand, according to James Waddell, head of European gas at consultancy Energy Aspects.

“If they can produce the gas and if it’s not consumed domestically in Algeria, there is spare export capacity,” he said. “The trouble is bringing on the upstream in Algeria quickly.”

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies estimates that Norway could raise exports by up to 5bn cubic metres and Azerbaijan by up to 3bn cubic metres.

The lack of alternative sources of piped gas sufficient to offset a drop in Russian flows leaves Europe with little option but to dramatically boost imports of liquefied natural gas.

LNG — natural gas that is supercooled and condensed — can be transported by ship and therefore does not need a pipeline. Replacing all Russian piped gas into Europe would require 112mn tonnes of LNG a year, equivalent to almost a third of today’s global LNG market, according to Bernstein Research.

While Europe wants to reduce its gas consumption through investment in renewables and energy efficiency, so is unlikely to need to replace all current flows from Russia, significantly more LNG will be required with the majority expected to come from the US.

“The hope is US LNG,” said Waddell. The world’s third-biggest LNG exporter behind Australia and Qatar, the US has already said it will help the EU secure an additional 15bn cubic metres of LNG in 2022 and more in future, without specifying how much will come from the US and how much from other countries.

In response to soaring European demand, Bernstein expects US producers to approve new projects that could more than double US LNG export capacity from 71mn tonnes (about 105bn cubic metres) in 2021 to more than 200mn tonnes a year by 2030. That would make the US by far the biggest LNG exporter.

Before then, the next major gas project scheduled to complete is the expansion of QatarEnergy’s North Field, the first phase of which should commence production in 2025, boosting the Gulf nation’s LNG export capacity to roughly 100mn tonnes a year by the end of 2026.

State-owned QatarEnergy produced 110bn cubic metres of gas last year, of which 24bn were consumed in Qatar and 86bn converted to LNG for export.

Among the seven western supermajors, UK-listed Shell was the biggest gas producer last year, extracting 103bn cubic metres from gas projects around the world, 44bn of which was converted to LNG, according to Wood Mackenzie.

LNG is central to Shell’s strategy. Record prices helped the company’s integrated gas division generate 63 per cent of the group’s $6.4bn earnings in the fourth quarter of 2021.

But any investment in new production — which is what would be required from the industry to offset lost Russian supply — is difficult for listed energy companies to approve when it could take a minimum of 15 years to pay off, said Wood Mackenzie’s Farrer.

“The international oil companies were all accelerating their energy transition ambitions, so an LNG investment has to fit within that criteria,” he added. “It has to pay back relatively quickly.”

Unlike in the oil market, where analysts expect some countries to continue to buy Russian crude, resulting in a partial redirection of trade that helps ease the supply crunch in Europe, flows of Russian gas cannot be redirected in the same way.

Gazprom piped about 10bn cubic metres to China in 2021 via the Power of Siberia pipeline, according to Wood Mackenzie. Moscow and Beijing have signed deals to increase that flow but the gasfields in eastern Russia, which supply China, are not connected to the western fields that supply Europe.

Whether or not formal sanctions on gas exports are introduced, Energy Aspects expects Russian supplies into Europe to fall by at least 21bn cubic metres this year when long-term contracts due to expire in 2022 are not renewed.

The lack of alternative sources of supply meant Europe would need to cut consumption, either by households or industry, to balance supply and demand, said Waddell.

“The one that is technically feasible and most palatable is to remove it from industry,” he added. “That means huge GDP cuts, job losses, rather than allowing people to freeze in winter.”

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here

Comments