Women in the frame: the Saatchi gallery’s all-female art show

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Julia Wachtel is a neo-Pop painter who casts an eye on celebrity culture. Mia Feuer makes art inspired by the environment. Virgile Ittah is a sculptor whose wax figures trigger reflections on human transience. Save that all three artists are still regarded as “emerging”, their work has nothing in common. Oh, apart from the fact that they are women.

This bond is enough to have brought all three, along with 11 other women artists, in to a show at London’s Saatchi Gallery called Champagne Life. It’s not enough. Although individually some of the artists here are strong — Jelena Bulajic’s meticulous mixed-media images of human faces, for example, are electrifying in their self-conscious realism — as a group they are less than the sum of their parts. The job of the curator is to provide context and nuance. Like a dinner party of random strangers, these works reduce each other to moments of embarrassed silence and awkward non-sequiturs.

So why bring them together? According to Nigel Hurst, chief executive of the Saatchi Gallery, the woman-only show is a response to the raw deal that women artists still experience. “We aim to celebrate the work [women do] in its sheer range and diversity.”

Hurst is right about the lack of equality. Among the shocking statistics gathered by curator and author Maura Reilly for a report published in Art News last year, “Taking the Measure of Sexism: Facts, Figures and Fixes”, was the fact that women account for the majority of American art students (60 per cent in 2006), but enjoy just 30 per cent of representation in US commercial galleries.

Public collections are equally skewed. For example on the walls of MoMA, just 7 per cent of works are by women. As for temporary exhibitions, the fact that Venice Biennale in 2015 counted 33 per cent of work by women, while two years earlier the figure was 26 per cent, typifies the big picture.

This disparity is hardly new. It is now more than 45 years since the art historian Linda Nochlin wrote her furious, seminal essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? in which she lambasted patriarchal society for failing to put women on a level playing field. Nochlin was in the vanguard of a wave of feminism that swept through the art world and beyond as writers such as Betty Friedan and image-makers such as Judy Chicago and Cindy Sherman paved the way for the less embattled generation of the 1980s.

By the mid-1990s, feminism was a dirty word in mainstream discourse. Susan Faludi’s Backlash (1991) outlines how relentlessly mainstream culture — still largely controlled by men — shamed women into staying silent.

On one level, nowhere have more glass ceilings been smashed than in the art world. On Art Review’s 2014 Power 100 List no fewer than nine women appeared in the top 20. Last year, Tate’s temporary exhibition spaces were entirely given over to female solo shows as Marlene Dumas, Sonia Delaunay, Agnes Martin and Barbara Hepworth went on display. And just last week, Frances Morris was appointed director of Tate Modern, one of the most powerful jobs in contemporary art. She joins a growing number of female institutional heads including Beatrix Ruf, who heads up Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum and Sabine Haag, director of the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna.

The result is an art scene that, from a gender point of view, is schizophrenic. Women are more visible than ever before. Yet simultaneously they have never lamented more loudly that they are not visible enough.

Behind the complaints lie a plethora of factors. On the one hand, there is a new, 21st-century tide of feminism. From websites such as Everyday Sexism to the launch of the Women’s Equality party, set up last year by the authors Sandi Toksvig and Catherine Mayer, women today are no longer prepared to ignore the iniquity of a society in which 51 per cent of the population accounts for just 29 per cent of MPs and 24 per cent of FTSE 100 directors but an astonishing 75 per cent of minimum wage earners.

As Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Gallery and one of the most powerful women in contemporary art, puts it: “Feminism is cool again.” But there are also dangers when women come under the spotlight purely because of their gender. Champagne Life is the tip of an iceberg of women-only shows right now. In Miami, for example, mega-collectors Don and Mera Rubell have brought together almost 100 women artists from Sherman to Yayoi Kusama and a host of less well-known names.

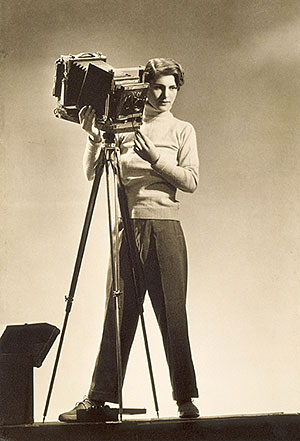

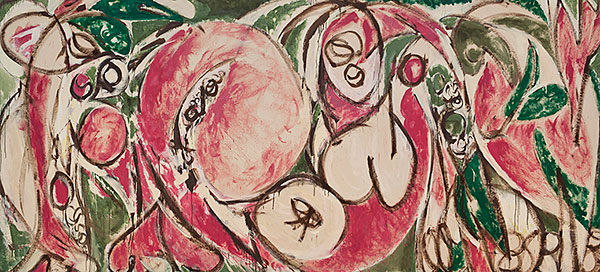

In Paris, the Musée d’Orsay is displaying women photographers from 1839 to 1945. In Frankfurt, the Schirn Kunsthalle has devoted its rooms to women who once showed at Der Sturm, the gallery that made Berlin the crucible of the avant-garde in the early 20th century. Soon, says Blazwick, the Whitechapel hopes to bring together a group of female Abstract Expressionists.

It’s hard to argue with the logic of the historical shows. As Blazwick puts it, “There’s a lacuna in history that needs to be addressed. We realised that a huge chunk of the story of [Abstract Expressionism] was missing.”

But what about shows where artists have nothing in common save their chromosomes? Maura Reilly believes they do perform a valuable service. Only by continuing to highlight women artists, she thinks, do we deny curators the excuse that “they couldn’t find any women” when asked why their rate of inclusion is so poor.

Many artists however, are wary of being ghettoised. “I’ve done two women-only shows and I’m not convinced,” says Nadia Kaabi-Linke, a conceptual painter and sculptor who won the Discoveries Prize at Art Basel Hong Kong in 2014. “It handicaps women as if they are saying: “Look how weak we are, we need a special place of our own.”

Dayanita Singh, the renowned photography artist who is based in Delhi and presided over an acclaimed solo show at London’s Hayward Gallery in 2013, notes that the categorisation by gender often goes hand-in-hand with ethnicity. “I want my work to stand on its own,” she says.

Last year, she was so fed up with “being called on to be the best woman Indian photographer” that she invented a spoof prize. Entitled the Anna Atkins Prize for the best Indian Male photographer, it requests applicants to submit a statement on “how you feel your ‘Masculinity’ has informed your photographic vision”.

Perhaps Kaabi-Linke and Singh feel uneasy because it is not just feminists who are keen to make women more visible. In recent years, market-makers have been enormously active in ferreting out women who are, as one blue-chip gallerist put it, “the bargains of their time”. (Currently, the highest priced female artist is Georgia O’Keeffe, whose painting, “Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1”, sold for $44.4m, a figure dwarfed by more than a dozen male counterparts, from Rothko, Pollock and Bacon to Gauguin, Cézanne and Picasso.)

It is thanks as much to gallerists, auction houses and fair organisers that we have discovered overlooked talents such as Phyllida Barlow, who was championed by Hauser & Wirth, and Geta Bratescu, one of the highlights of the 2012 Frieze Spotlight section on neglected masters. In February, Bonhams will be the first auction house to dedicate one chapter of a modern and contemporary sale to five women artists: Yayoi Kusama, Germaine Richier, Louise Nevelson, Carla Accardi and Dadamaino. Of course, it’s laudable that women artists are being valued more highly. But let’s not forget that the ill wind that once blew them into poverty is now also doing their sellers — and buyers — the power of good.

It’s notable too that high-glamour fashion and lifestyle brands are queueing up to sponsor women-friendly projects. In Milan this year, the Nicola Trussardi Foundation, the cultural arm of the fashion house, sponsored a vast show called The Great Mother. Although it did not exclude work by men, the relentless maternal theme reeked of biological essentialism. The Saatchi show is sponsored by Pommery Champagne. (Hurst said the tie-up was ironic. “It’s meant to show the contrast between the perceived glamour of the art world with the reality of long, lonely hours in the studio.”) Blazwick, meanwhile, admits that behind the decision to make Whitechapel’s biennial MaxMara prize available only to women was the desire of the Italian fashion house that sponsors it to have “something in line with their brand”.

Asked why so many women artists continue to take part in female-only forums, Kaabi-Linke said: “Because you feel you can’t afford to say no.” But with so many powerful people keen to co-opt them as flagbearers, women should feel able to refuse. After all, they are in demand because they’re worth it.

‘Champagne Life’, Saatchi Gallery, London, to March 9. saatchigallery.com

Photographs: Steve White; The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society/DACS, 2016; Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Comments