Vaccines hold potential to curb antibiotic resistance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The battle against antibiotic resistance is often portrayed as a race between pharmaceutical science and bacterial evolution. Yet health experts warn that prevention is better than cure — and the potential of vaccines in combating drug-resistant infections is often overlooked.

Of the six bacteria that are responsible for the most deaths linked to drug-resistance — a combined 929,000 fatalities per year — there is a licensed vaccine for just one: Streptococcus pneumoniae, which can cause pneumonia and other illnesses.

“Even though those of us in the field appreciate that vaccines are really the way to go in terms of dealing with [antibiotic resistance], this isn’t actually even appreciated properly in the science community at large,” says Professor Calman MacLennan, an Oxford university immunologist who runs BactiVac, a global bacterial vaccinology network.

“There are limited tools to fight AMR [antimicrobial resistance, another term for antibiotic resistance] at the moment, so we should make better use of vaccines,” he says.

Approved vaccines are available for three of the 12 bacteria on the World Health Organization’s list of antibiotic-resistant “priority pathogens”: Streptococcus pneumoniae; Haemophilus influenzae; and Salmonellae.

But high prices and poor medical infrastructure have often held back uptake in low- and middle-income countries, where the available vaccines are most needed to address rampant AMR, which has been driven by the overuse of antibiotics.

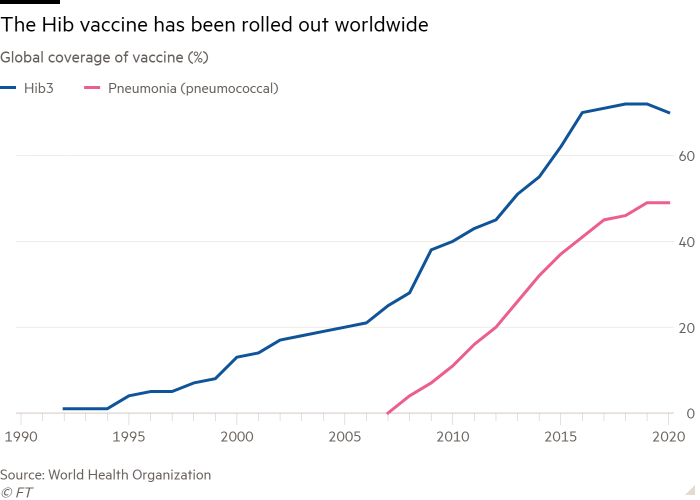

The Hib conjugate vaccine, which is given to children shortly after birth to protect them against Haemophilus influenzae, which can cause meningitis, has proved the most successful, having precipitated a sharp decline in infections across 192 countries since it was first administered in 1992. The WHO estimates global uptake was 70 per cent in 2020. That has meant fewer of the remaining infections are drug-resistant since antibiotic use is lower.

“A lot of what’s been driving resistance is all the antibiotics we’re giving to children, so the Hib [vaccine] has had a huge impact,” explains Martin Blaser, professor of medicine and pathology and laboratory medicine at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “Hib used to be a huge problem among young children and that has been virtually pushed aside, thanks to getting the logistics and deployment of the rollout right.”

By contrast, uptake of the pneumonia shot has stalled in recent years. From 2010 to 2015, coverage increased from 11 to 37 per cent. However, in the five years to 2020, it rose just 12 further percentage points, to 49 per cent.

MacLennan worries that the rollout could “plateau long-term” as — despite $3.3bn of support from the Gavi vaccine donors’ alliance since 2009 — “just short of 50 countries have yet to introduce it”.

Often, poorer countries that are not eligible for Gavi’s support end up “falling through the gaps”, according to Alan Cross, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland.

“In terms of uptake, the big problem there is, of course, the cost of goods,” he says — adding that “governments have to weigh the cost of the vaccine with the amount of coverage they will get”.

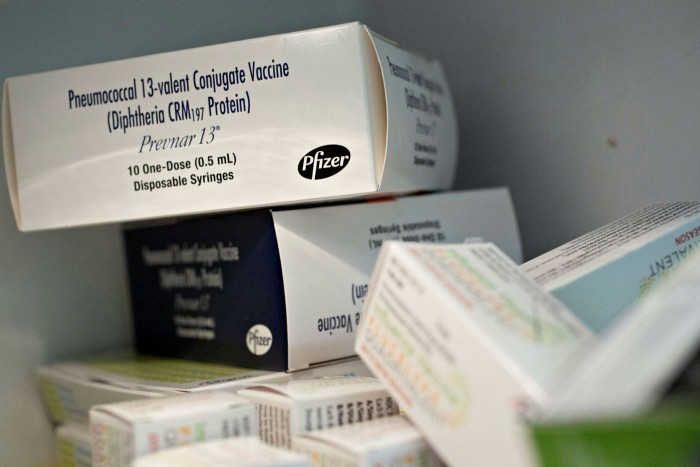

Prevnar, a shot made by Pfizer covering 13 bacterial pneumonia strains, is sold privately for $211 per dose — which generated $5.9bn for the US pharmaceuticals group in 2020. It was the company’s best seller until it released a Covid-19 vaccine with German drugmaker BioNTech. Gavi and other charitable enterprises have been able to procure the jab at much-reduced prices of $10, though. A rival pneumonia shot made by the Serum Institute of India is being supplied to Gavi for just $2 a dose. And, recently, US and European drug regulators have approved a new version of the jab that covers 20 strains.

However, China is yet to introduce either a Hib or bacterial pneumonia vaccine. “That’s a bit of a problem,” MacLennan says. “If you’re going to have one country that doesn’t introduce the jabs, you’d rather it not be the most populous country in the world.” A study by researchers at Wuhan University concluded antibiotic overuse in China presented “a serious public health problem”.

Meanwhile, insufficient funding for research and development, as well as challenges in carrying out large-scale human trials, have hampered the pipeline for future bacterial vaccines.

Vaccines for some significant antibiotic-resistant infections — including shigella, E.coli and non-typhoidal salmonella — all have “sufficiently advanced R&D” that bringing them to market is a realistic prospect in the short-to-medium term, according to a 2018 report commissioned by medical charity the Wellcome Trust.

Even so, Cross warns that one serious obstacle remains. “A number of these have the opportunity to be successful, but the big hurdle on all this is how to test them for efficacy because, unlike influenza or other mass infection scenarios, there just aren’t enough cases to do your standard clinical trial,” he explains.

A case in point is a jab for shigella, a type of bacteria that typically causes dysentery. It was tested in a human challenge trial in 2015, where volunteers are deliberately infected, with half of the group of 60 having been given the vaccine and the rest a placebo. The results, published in EBioMedicine, showed a 51 per cent reduction in symptoms, including fever and dysentery, and a 70 per cent reduction in severe diarrhoea.

Still, experts believe a fully licensed shigella jab is at least a decade away. “People have been working on shigella vaccines for the last 50 years so it’s not imminent,” says Blaser.

However, he believes that the success of Covid-19 vaccines has “really changed the game” by showing what is possible in a short space of time with the right level of investment.

“It costs a lot to develop new vaccines so a lot of these vaccines will require government backing to get them over the line,” Blaser says, adding that new weapons against antibiotic-resistant infections cannot come soon enough.

“Antibiotics were a great miracle when they were introduced in the 1940s, and we’ve been digging a hole of resistance for the last 75 years,” he warns. “The hole keeps getting deeper and what we need to do is start filling in the hole, Vaccines are an important part of getting us out of that hole.”

Comments