The real opportunity of Brexit

This article is an on-site version of our Brexit Briefing newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

It is a stock phrase of Boris Johnson’s government that it seeks to “deliver on the opportunities of Brexit”. Indeed, barely a press release or a government statement passes without this appearing somewhere or other.

But five years after the UK voted to leave the EU, those “opportunities” remain stubbornly ill-defined, beyond a broad commitment to notions of lighter-touch, nimble regulation in key areas of UK economic life, such as global finance and the life sciences.

The obvious difficulty with the UK exercising its new regulatory sovereignty to create its own rules — however nimble — is that from the perspective of global industries such as pharmaceuticals and medical device makers, the UK amounts to only a few per cent of the total global marketplace.

This is why industry has raised concerns, as noted in a previous edition of Brexit Briefing, over the implementation of the new UKCA quality assurance mark that essentially duplicates the EU’s existing CE mark regime, adding UK-specific cost and complexity for no obvious gain.

This is particularly true for fields such as medical devices, which have to be sold globally to be commercially viable, and why UK industry and experts recently warned over risks of divergence for divergence sake.

The risks of failure in the regulatory sphere are political as well as commercial. If the UK, which represents just 4 per cent of the global market in medical devices, gets the future regulatory environment wrong, it will mean fewer products being available to NHS patients because industry licenses them first for the bigger participants, notably the EU and the US.

But while there can be no ignoring the limiting factor of size, regulatory experts argue that there is potential for the UK to seize a significant Brexit dividend by regulating better, and indeed could become a truly “world-beating” force in what is called “regulatory science”.

The opportunity is not so much cutting regulation — “slashing Brussels red tape” in the popular Brexit narrative — but in fundamentally changing the way in which the UK approaches and manages regulation.

The government’s TIGRR report on post-Brexit regulatory reform led by arch-Brexiter Sir Iain Duncan Smith alluded to this, but was still fundamentally based on the notion that regulators and their regulations are obstructive rather than enabling in nature.

Yet the Covid-19 pandemic has actually been a public showcase for strong and clever regulators, making sure that useless or dangerous ventilators and PPE did not enter hospital wards; fast-tracking coronavirus vaccines and keeping unreliable Covid tests from the market.

The real opportunity of Brexit, therefore, says Professor Christopher Hodges, a global regulatory expert at the University of Oxford, is to fundamentally change the thinking behind the way the UK regulates, releasing potential in the process.

The step-change, he argues, must be away from a rules and sanctions-based approach — typified in the EU’s unwieldy new Medical Devices Directive, which is causing massive bureaucratic headaches in the industry, forcing businesses to take products off the market — to a more trust-based approach that is built around all participants in the process working towards common goals.

Hodges cites the airline industry as an example of where the common endeavour of keeping planes safely in the air achieves the shared outcome that both operators, regulators and indeed passengers are looking for. From the air traffic controller, to the worker out on the tarmac shutting the plane’s luggage compartment, it is the common endeavour, not fines and sanctions, that ultimately achieves safety.

“The TIGRR report missed a big trick,” says Hodges. “The EU has a structural problem because it needs to harmonise rules across 27 countries. But if the UK modernises its whole approach based on ethics, trust, evidence, problem-solving and putting an ethical code at [the] centre rather than a load of rules, then it can do extraordinarily well.”

These ideas that now underpin new regulatory science — and which are already featured in a lot of new corporate thinking on incentivising productivity and performance — might seem abstract, but the ultimate aim is to make a difference on the ground for UK plc.

In the medical devices field, where 80 per cent of UK companies are SMEs, that difference potentially means clearer lines to market, a faster and cheaper approvals process and with the UK becoming an increasingly attractive test-bed for new products. Business and patients both benefit.

Work is going on to advance these ideas that overturn centuries of a “carrot and stick” approach to getting the best out of people and the systems they operate in, but will require collective buy-in from government, industry and regulators themselves.

Bids are being prepared to create a UK version of the Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSIs) that have been created in the US by the Food and Drug Administration to drive better, smarter regulation.

The Birmingham Health Partners (BHP) cluster, which brings together academics from the University of Birmingham and local NHS Trusts released a report in July 2020 on the role of advancing regulatory science in the healthcare sector.

Professor Melanie Calvert, director of BHP’s Centre for Regulatory Science and Innovation, says that the UK’s departure from the EU provides “a clear opportunity” to capitalise on the kind of flexibility demonstrated through the coronavirus pandemic.

But to be globally competitive, she warns, the UK needs to invest in regulatory science in order to capitalise on the coming wave of inventions that will flow from digital tools, robotics, artificial intelligence and new therapeutic approaches, such as cell and gene therapy.

“Developing a national strategy for UK regulatory science will allow us to be both globally competitive and internationally collaborative. Enabling groundbreaking products developed here to be efficiently deployed around the world will not be straightforward, and finding the best outcomes will rely on forward-thinking UK innovation in regulatory science,” she says.

In short, there is a regulatory dividend to be won here, but it’s not quite as commonly conceived, and will require investment (not 25 per cent staff cuts to the medicines and medical devices regulator as the Financial Times reported last week) and a collective effort among officials, regulators and business on how we do things.

Thank you to everyone who has already filled in our reader survey. We would love to know what you think of Brexit Briefing, so would really appreciate it if you could take the time to fill it in. That way we can ensure that the newsletter remains an essential weekly read.

Brexit in numbers

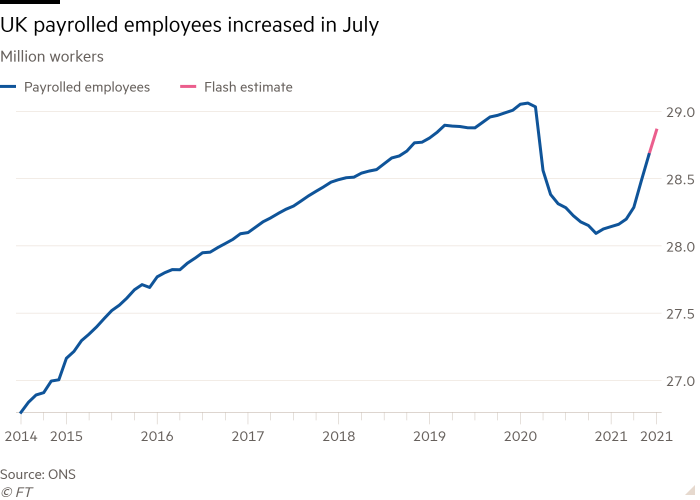

Encouraging signs of Covid recovery continued this week with the latest increase in job numbers pushing the headline unemployment rate down to 4.7 per cent. The recruitment market is “exceptionally buoyant”, according to staffing agencies.

But there remains a Brexit sting in the tail for many businesses including hospitality and logistics, which have experienced recruitment difficulties caused in part by the ending of free movement and the government’s bar on low-skilled immigration.

The government wants business to “adjust” and argues that the 5.6m EU workers who applied for settled status after Brexit should give sufficient flexibility to industry as that process takes place.

But with Covid restrictions only now lifting, it is too early to say how many EU workers will come back to jobs in the UK. Many, like truck drivers, may have discovered rival temptations during the lockdown, such as working closer to family and, in many EU countries, not having to drive on Sundays.

Business groups continue to call for short-term visa solutions to deal with the shortages, but the government is ideologically wedded to this new policy and is apparently loath to set precedents by flexing.

But as the ONS Labour Market statistics dropped this week, that’s what business said it needed.

Elizabeth de Jong, policy director at Logistics UK, said the industry needed “a short-term flexible solution on immigration to help manage the current shortages while new recruits are trained to enter the sector”.

While Suren Thiru, head of economics at the British Chambers of Commerce, warned that a “deep-rooted squeeze on labour supply from the impact of Covid and Brexit” risks crimping economic activity. “A more flexible immigration system is also needed to ensure that firms get access to the workers they need,” he said.

No sign, as yet, of that memo having reached the Home Office.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

Poultry producers are blaming a run on chickens in the UK on post-Brexit immigration rules, saying the struggle to hire workers risks “irrecoverable food shortages”. One of Britain’s largest chicken producers, 2 Sisters Food Group, said on Wednesday that a “chronic” shortage of staff to process birds had left clients, including Nando’s, short of meat. While the workforce has been affected by coronavirus, post-Brexit immigration restrictions have had a more severe effect, according to 2 Sisters.

Britain-Ireland freight flows have fallen 29 per cent since the Brexit deal came into force in January, according to an official report. Amid post-Brexit trade frictions, Irish businesses have opted to send goods directly into Europe to avoid the risk of UK border delays. Britain’s share of ro-ro traffic with Ireland, meanwhile, has fallen from 84 per cent two years ago to 67 per cent in the second quarter of this year.

And one EU story for the road. If the German Greens gain power in September’s federal election, expect a sharp break from the policies of outgoing chancellor Angela Merkel. In a rare interview with the foreign press, Annalena Baerbock, the Green candidate for chancellor, called for looser limits on EU member states’ budget deficits and debt levels. Baerbock has also been tougher on foreign policy than her main rivals, suggesting that the EU imposes import duties on state-backed Chinese companies and accusing the Merkel government of being soft on Moscow.

My colleague, Philip Stafford, will be your Briefing host next week. He’ll be writing about the UK’s unwillingness to repeal the banker bonus legislation — even though nobody likes it. You won’t want to miss that.

I’ll be back in a fortnight and would still very much appreciate your feedback on this newsletter and your stories if you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU’s single market and custom union. Contact me at brexitbrief@ft.com.

Comments