The next academic revolution will be televised

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

For staff used to teaching face to face, the new world of videos, live streaming, webinars and online forums takes some getting used to.

They understand that it helps students, democratises education and enhances their institution. Some are enthusiastic early adopters. Yet for others, talking to a camera can be disconcerting.

“The first time is horrible but when you have done 10, it starts getting normal,” says Sandra Sieber, professor of information systems at Iese, the Barcelona-based business school. “We have to learn and adapt to the new environment,” she says. “This is the moment when I am starting to feel old — and I am 40-something.”

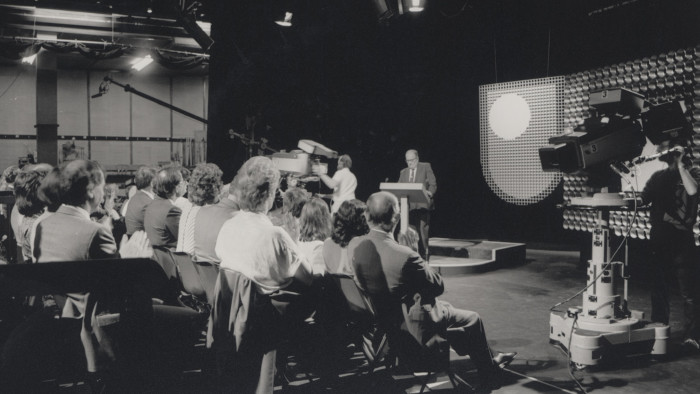

Online learning for MBA students has been around for up to 20 years in some institutions. At first it was largely a matter of videoing lectures, which some students criticised as boring, but techniques have become more sophisticated as technology has advanced.

Talking heads can be interspersed with video and audio clips, graphics and opportunities to ask questions or take part in polls. There are online discussion forums. Seminars and team projects are undertaken via video group conferencing. Business schools have created studios and e-learning teams to support teaching staff.

Iese says it has embraced digital learning across its programmes and also runs massive open online courses (Moocs) via the Coursera platform.

Prof Sieber was until recently academic director of Iese’s global executive MBA, much of which is taught digitally.

She says the school began by providing case studies and financial analysis online, but has moved on. Videoconferencing, for example, allows group role playing assignments in which a student might pitch to an “investment committee” made up of his or her peers.

A big challenge is keeping students engaged. “You don’t necessarily see who is bored and who is engaged, so we need to find new ways of engagement in our sessions,” Prof Sieber says. That means talking in five- to seven-minute segments instead of 45 minutes and building in “moments of interactivity” such as a poll or a question.

Ray Irving, director of e-learning at Warwick Business School, says: “There has been a real revolution in the last couple of years when we have seen more convergence between face-to-face learning and online learning.”

Warwick runs a distance learning MBA and has offered Moocs on topics such as behavioural science and big data via FutureLearn, an Open University platform. Now it is applying online techniques to on-campus courses, such as streaming a guest lecturer who might be based abroad.

Mr Irving heads a 15-strong e-learning team that teaches academics how to deliver their material in front of a camera. “We go through dry runs, provide autocues, we talk about what they should wear, how they should sit, we will break it into chunks and intersperse it with graphics,” he says.

Teaching drives the use of technology at Warwick. Mr Irving’s staff will ask an academic what works for their subject and attempt to translate that online.

Diana Laurillard, professor of learning with digital technologies at University College London’s Institute of Education, says teaching online successfully requires a great deal of support from the institution that is providing the course.

Academics are not unwilling, she adds. “What academics are all about is getting the message out.”

Some techniques work better than others. Prof Sieber says some case studies are too complex to work effectively online. When more than 15 students take part in a video conference, Iese asks them to switch their cameras off except when making a contribution because it can be confusing to have too many faces on screen.

Peer-to-peer learning, in which students help each other, can work well, particularly in Moocs when the large numbers make it hard for professors to respond to every comment or question.

Leeds University Business School does not have an online MBA but is embracing digital elements. It has given iPads to masters students to use in class for things such online polls. Leeds aims to achieve “personalised learning pathways”, so students can choose material online that is useful to them.

Prof Laurillard adds: “It’s about making sure leaders in the education system understand what can be done here, the value and potential of it. There are so many challenges in education that technology can help with.”

Comments